Migrants march toward the Deconcini Port of Entry in Nogales, Sonora in a demonstration asking President Joe Biden to restore the U.S. asylum process.

Migrants march toward the Deconcini Port of Entry in Nogales, Sonora in a demonstration asking President Joe Biden to restore the U.S. asylum process.

On a rainy Saturday in Nogales, Sonora, a group of migrants perched just below the border wall shared a single squeaky megaphone. They addressed an audience of a few hundred people huddled below.

"It is injustice, my friends, injustice that has us here," the first speaker, said in Spanish before handing the megaphone to the translator.

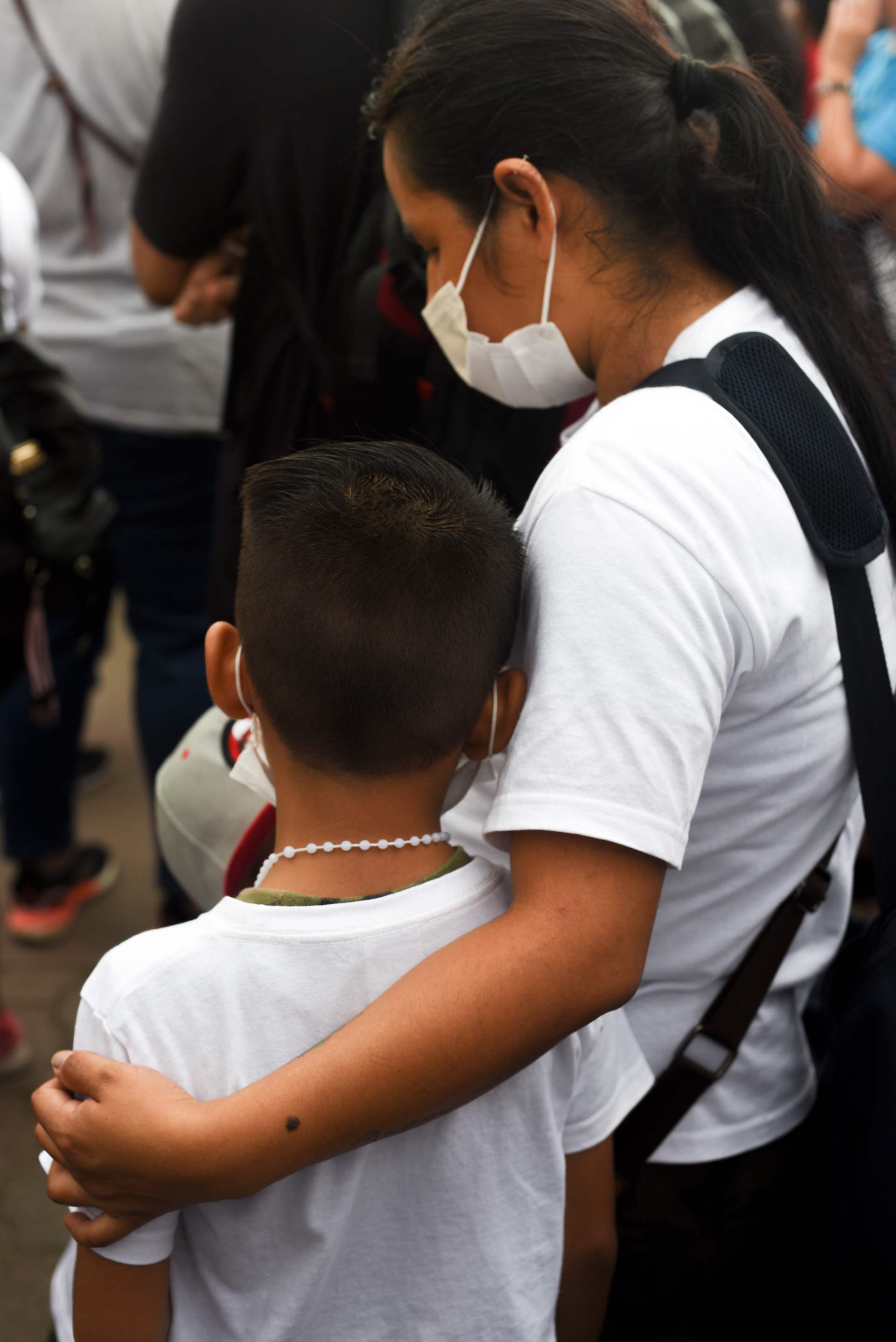

VIEW LARGER A Mexican mother comforts her son after the family's asylum claim was turned away at the DeConcini Port of Entry in Nogales. The family approached the international crossing in the hopes of speaking with a port officer about asylum, but Customs and Border Protection officers closed the metal gate to the port and shut down the pedestrian crossing temporarily.

VIEW LARGER A Mexican mother comforts her son after the family's asylum claim was turned away at the DeConcini Port of Entry in Nogales. The family approached the international crossing in the hopes of speaking with a port officer about asylum, but Customs and Border Protection officers closed the metal gate to the port and shut down the pedestrian crossing temporarily. Around them, migrants and advocates on both sides of the border held up homemade banners with messages in Spanish and English asking President Joe Biden to restore asylum. Another sign depicted a family staring up at the border wall.

Next month, the Centers for Disease Control is slated to re-assess the use of Title 42. The little-known public health protocol was enacted by the Trump administration at the onset of the pandemic in March of last year and allows Border Patrol agents to turn most migrants they encounter back across the border to Mexico almost immediately on public health grounds.

"I do not understand the reason they deny us the right to asylum just for not having a paper to enter the U.S.," said Karla, a Guatemalan mother who said she fled to Mexico with her two children after her husband was killed. "Why is it that those who have American papers can come and go whenever they want with no COVID test and even without a mask?"

The U.S.-Mexico border has been closed to non-essential travel for more than a year. The policy, which U.S. officials just extended for another month, bars non-citizens from entering the U.S. but does not restrict U.S. citizens from traveling back and forth.

Migrants and advocates on Saturday said all the demonstrators had tested negative for COVID the day before. Many had already been vaccinated.

"If a person who is seeking asylum presents themselves to a U.S. immigration officer and they express that they have fear of return, and they’re looking for asylum, then there is supposed to be a process in which they are processed into the U.S. and they receive what is called a credible fear interview," said Chelsea Sachau, a lawyer with the legal advocacy group Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project.

From there, she said migrants enter an immigration case and are eventually seen by a judge. But under Title 42, migrants at the border don't have those options, or any options, except to wait. Sachau said until until that policy is repealed, everyone will remain in limbo.

That’s the case for Carlota, a single mother from the state of Guerrero in southern Mexico. We’re using an alias because she’s worried speaking could affect her chances for asylum. A few weeks before the march, she and a few dozen other migrants fluttered around the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, painting banners and getting organized for the event.

She fled her home with her two young children this fall when gang members burned parts of her village down. She said she can’t return home and is scared to stay in Mexico. She arrived to the Arizona border at the end of July hoping to apply for asylum in the U.S. and join family.

“But they don’t listen to us, they don’t listen to us,” she said in Spanish.

VIEW LARGER Migrants, advocates and faith leaders gather on both sides of the border wall in Nogales to read out the names of families seeking asylum and give testimonies.

VIEW LARGER Migrants, advocates and faith leaders gather on both sides of the border wall in Nogales to read out the names of families seeking asylum and give testimonies. Now she rents a tiny, overpriced apartment in Nogales, Sonora she said she can barely afford. Others are staying in shelters or just living rough.

Just a few months ago, the Department of Homeland Security had a program that allowed humanitarian organizations to recommend some migrants to bypass Title 42 restrictions.

But that ended weeks before Carlota arrived. It was a small window that’s now closed.

“I think it is a right that they are taking away from us,” she said. “It’s a right that all humans have, to ask for asylum, or at least to be listened to.”

That’s why she joined the march on Saturday.

Her family was one of 25 who planned to approach Nogales’ Deconcini Port of Entry accompanied by lawyers and faith leaders from Tucson, Phoenix and around the country. They hoped to speak with a U.S. immigration officer one-on-one to begin the long process of applying for asylum.

A group of several hundred migrants and supporters waited at the gates of the port as Sachau, the Florence Project lawyer, and Bishop Edward Weisenburger of Tucson, guided the first family past the turnstile toward the crossing.

Minutes later, they all returned. The family wiped tears from their eyes. Customs and Border Protection officers had closed off the port.

"I think it’s very telling that one family alone asked for asylum and asked to have processing, and they shut down the entire port, for a single family,” Sachau said.

For the next several hours as the port re-opened, families waited for their chance to ask for processing. One by one, each was turned away.

VIEW LARGER Faith leaders comfort migrant families who have just been turned away from the port of entry after attempting to ask CBP officers for asylum processing in the U.S.

VIEW LARGER Faith leaders comfort migrant families who have just been turned away from the port of entry after attempting to ask CBP officers for asylum processing in the U.S. Carlota reached the front pushing a stroller with her young daughter inside. Her vaccine card, COVID test results and asylum paperwork were at the ready in a neat plastic folder. Her 8-year-old son followed behind her, reciting the English words he learned and adjusting a bulging backpack.

He burst into tears when they, too, were turned away.

“Maybe today it won’t be,” Carlota said, bending over to comfort her son. “But maybe one day.”

Carlota and her kids returned to their apartment that night. She said despite the disappointment, she’ll keep starting each day.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.