The Abrahem-Mohamed household in Tucson.

The Abrahem-Mohamed household in Tucson.

It is dinnertime in the Abrahem-Mohamed household. Grandma is watching the 4-year-old and the baby.

The mother, Fatuma, is cutting vegetables to put into a soup, while the father is still at work. A normal day in the life of a Tucson family. But the back story of this family is far from normal. Getting to Tucson was a 26-year journey from Somalia.

“I came from the Dadaab Refugee Camp. I came here to have a better life and to live in a peaceful country,” Fatuma told Arizona Public Media through an interpreter.

Dadaab the largest camp of its kind in the world. It sits across the border from Somalia in Kenya, and around 350,000 people live there. It’s been there for years, taking those fleeing civil war in their homeland. Since 1991, more than a million people have been killed in the war in Somalia.

Now, after a quarter-century of sheltering the most vulnerable from the Somali Civil War, the Kenyan government is moving to close the camp. Fatuma and her immediate family gained asylum in the U.S. after three years of vetting and were brought to Tucson by the aid group International Refugee Committee.

“We were the first arrivals to come to that refuge camp,” Fatuma said.

She was 9 years old. She lived there more than a decade, met her husband in the camp and bore her two children there. She recalled hardships growing up there.

“Those people who would distribute food to the refugee camps only every 15 days. And this is not enough. We can’t go outside of that refugee camp to buy some stuff. So it’s horrible. We had to stay in that area, and you can’t go anywhere else.”

Fatuma and her family arrived in Tucson in November. Within two months she and her husband were working and, she is quick to add, paying taxes.

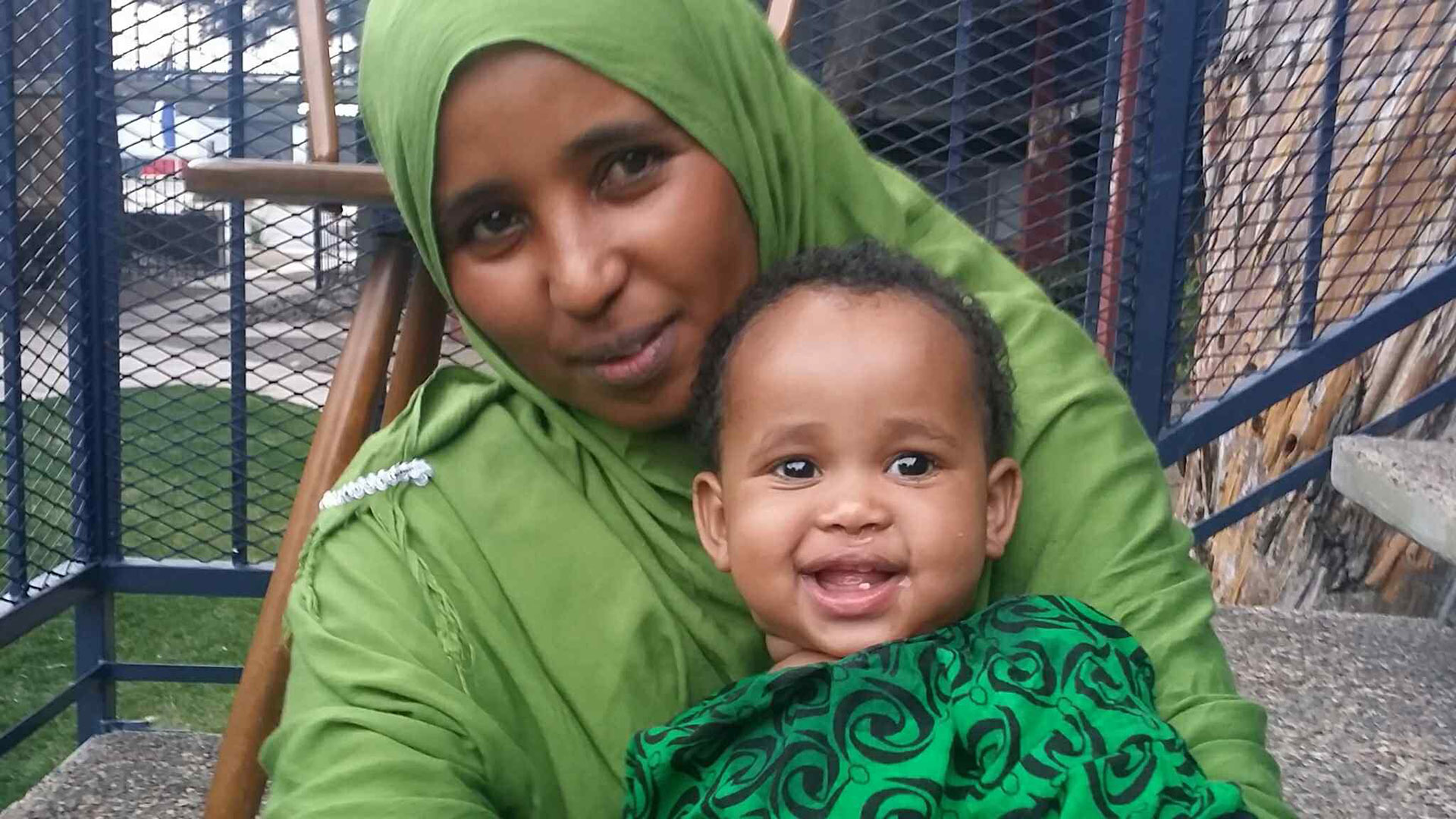

Fatuma and her child.

Fatuma and her child.

“I feel like I’m in a good place. I feel like I am in a peaceful area. This is the land of freedom – so I am so happy to be in this place.”

But she left something behind in the refugee camp.

“My family was supposed to come on Jan. 31, before Trump signed that executive order. They were taken back to the refugee camps and they were told until further notice they can’t come to the United States.”

Fatuma's sister and two brothers are still in Kenya. That's the dilemma facing Fatuma’s family and untold numbers of other refugees who are caught somewhere between their homelands, the lengthy vetting process and the U.S.

Until now, refugees were not a part of terrorism concerns in the U.S., said Jeffrey Cornish, head of Tucson’s branch of International Rescue Committee.

“After being in this business for decades we are very satisfied with the security vetting process,” Cornish said. “There have been very few incidents. In fact there has only been three incidents with refugees since 1975. For us the security vetting process has been very well thought out and working.”

Fatuma knows what she would tell Trump if they could meet face to face.

“I want him to understand that he is inside his house, for example, and his son is outside the house. And the door is closed – it is shut. And the child cannot come into the house. How would he feel? That’s what I want him to understand. Like now, he is putting a divider between me and my family.”

For Fatuma, that divide has left her sister and two brothers still waiting in that crowded refugee camp in Kenya.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.