The Pima County Juvenile Court system is ripe for backlogs in cases of children awaiting parental reunification or adoption because expected budget cuts will slow services, say to Pima County officials.

County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry warned last month state budget cuts will mean $23 million in county budget reductions, and one of the few services with a flexible budget is the judicial system, including the juvenile court in which dependency cases for children who have been removed from their homes are approaching historically high numbers.

Some of the few places to cut within the juvenile court system are in the programs that help usher cases through the system, educate parents, and restore family units, said Chris Swenson-Smith, the child and family services director of the Pima County Juvenile Court.

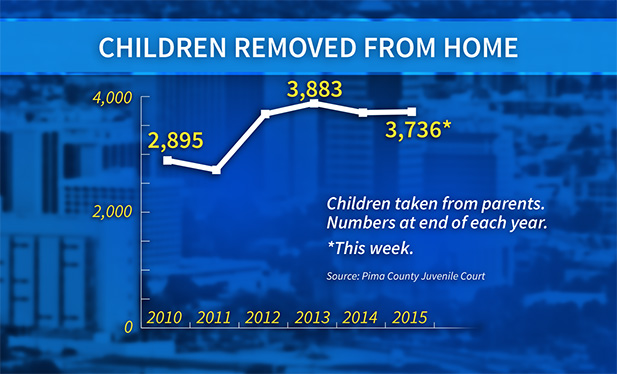

“Demand isn’t rising this year, although we have stayed at that high level that we were at in 2013 after a huge increase in 2012,” Swenson-Smith said. “I expect that the number of filings of child welfare, dependency, child abuse and neglect is going to go up after some of the state budget cuts to services that families need.”

The jump in numbers of children removed from their homes in 2012 was “on the heels of some major services cuts,” she said.

Behavioral health funding cuts, and reductions to state-funded family services, including food stamps, contribute to the increase in children who need services, Swenson-Smith said.

There haven’t been enough foster homes for a long time, she said.

“That’s definitely something that we need help with in Pima County. Obviously the better thing would be to put in some prevention services so they wouldn’t have to be removed from their parents’ care,” she said. “Once they are (removed) it’s really, really vital that they’re put in a safe place to reduce the amount of trauma that they’re feeling,” she said.

Removing a child from parents The state Department of Child Safety is the agency that receives reports of neglect or abuse. It is charged with investigating the allegations, then acting in the child’s interest based on the findings. If that means removing a child from her family, the state is responsible for putting services in place to reunite the family or place the child permanently in a safe environment.

The department files a petition with county juvenile court once it has removed a child from his or her home.

“We have the same mission, and that is to make sure that children are safe, that we restore as many families as we can,” Swenson-Smith said. “In the end, that families leave in a better place than when they came to us, that children thrive and that we don’t see them back again in court.”

Volunteer help

One way to help make its budget is by asking volunteers to assist in court roles. The Pima County Juvenile Court is always looking for court appointed special advocates, or CASA, Swenson-Smith said.

Art Hoffman volunteered to be an advocate less than a year ago. His role is to speak on behalf of the children’s best interests, as lawyers, judges and the state child welfare system try to balance competing interests and policies.

“When you’re in a court situation, all of the participants have various roles that they have to fill. And many of them have to abide by law or they have to abide by the wishes of the child, whereas a CASA we’re independent,” he said. “We’re volunteers, we’re appointed by the judge and we’re really trying to look out for the best interest of the child and represent that in the court setting.”

There are 144 CASAs to serve 3,800 children who have custody or parental rights cases in the system, he said.

That’s not enough to serve every child with even a monthly visits. The advocates also are expected to write a report before every court date and appear at court hearings with the parties in the case.

“There’s a large number of children that really, really aren’t represented,” Hoffman said. “The children aren’t really aware of what’s going on around them, they don’t really know how to help. There’s a lot of good people around them trying to help and provide them services, we just need to tie them to those services.”

Budget questions The $23 million deficit for the county, and Huckelberry’s order of 2 percent cuts for every department, means the juvenile court is evaluating every program it offers, with attention to whether it is mandatory in state laws or regulations, Swenson-Smith said.

“So we’ve found ourselves in the position of justifying some of the things we do at the court, family drug court, remediation court, things that aren’t mandated and yet without them, we wouldn’t be able to move cases along,” Swenson-Smith said.

That could lead to a case backlog that prevents mandatory services from implementation, she said. She said she hopes cutting the juvenile court programs that aren’t mandatory will be more expensive in the long term.

For the 3,800 children awaiting resolution of their family situation, Swenson-Smith said, “if we can’t get those cases moving along and get children into permanent homes we’ll begin to see a backlog and then we won’t be able to do some of our mandated duties at the court.”

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.