Dorey and Ken Conway lead the Yuma Foothills Library astronomy group.

Dorey and Ken Conway lead the Yuma Foothills Library astronomy group.By Amanda Solliday, Arizona Science Desk

As the New Horizons spacecraft moves beyond Pluto and scientists begin to sift through the data of the historic flyby last week, a group of citizen scientists is also taking a look at the solar system’s frontier.

Coordinated by one of the New Horizons team members, amateur astronomers are focused on the Kuiper Belt, a band of frozen objects on the very outskirts of the solar system.

A husband and wife team, Dorey and Ken Conway, lead the amateur astronomers at the Yuma Foothills Library, on a starry Tuesday night.

The Conways enter the celestial coordinates, and their telescope points to a star. To verify the position of the star, the team compares what they see through the telescope to a map of the star field.

They are hoping to catch a glimpse of a shadow as Weywot, an object in the Kuiper Belt, passes in front of the star. This is called an occultation and will only take seconds.

“All of a sudden, one of the dots will just blink out and then come back,” said Dorey Conway.

Kuiper Belt objects are difficult for astronomers to see because they are far away and quite small. With a 1,473-mile diameter, the dwarf planet Pluto is the largest and most famous object in the ring of debris.

To make the observations a bit easier, a chain of telescopes is situated where there are clear Western skies.

The Yuma team is at the southernmost tip of 55 groups. The other telescopes are located about every 30 miles north of Yuma, stretching in a line up the western United States.

Together, they form the Research and Education Collaborative Occultation Network, or RECON.

“All the communities from Yuma to Canada are all focusing on this one part of the sky, and they’re all recording the same thing,” said Dorey Conway.

When an occultation occurs, researchers don’t expect all of the telescopes will capture the shadow. But Ken Conway said even the absence of the shadow from some locations tells astronomers something about the object they are focused on.

“The number of stations that can record the event can give some idea to the shape and mass of these objects that we’re recording,” Ken Conway said.

Having telescopes spaced miles apart helps better measure the size of the shadow. And knowing where exactly where that shadow will fall on the Earth’s surface is a little tricky, said John Keller, a planetary scientist and one of the two team leaders of RECON.

“The Kuiper Belt objects that we’re looking at have only been really measured the last 10 or 15 years, and they have orbits that take 300 or more years to go around the sun," said Keller. "So if you’ve only watched something for 10 or 15 years or five percent of its orbit, it’s hard to know where exactly the object is."

The large number of telescopes increases the chance of capturing the shadow of an object, Keller said. The team also roughly knows the speed of the object. So they measure the time the shadow is cast, and then can multiply that by the speed to determine the size of the object.

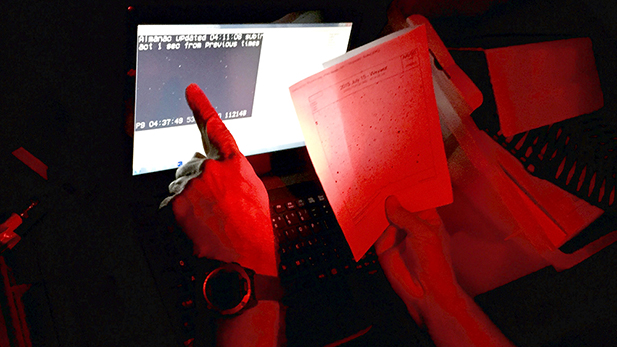

Ken Conway matches a star field map to the view seen through his telescope and recorded on a laptop.

Ken Conway matches a star field map to the view seen through his telescope and recorded on a laptop.RECON was first envisioned by one of its current project leads, Marc Buie. He is an astronomer at the Southwest Research Institute and is also a member of the New Horizons team.

The RECON project observations will focus on Kuiper Belt objects that are about 60 miles wide or larger. Keller said there are about 100,000 of these in the Kuiper Belt.

The chain of RECON telescopes can do something even one of the most powerful telescopes cannot. The orbiting Hubble Space Telescope doesn’t always distinguish if objects in Kuiper Belt are actually doubles or what’s called a binary system.

“There are probably doubles that are too closely spaced that even Hubble can’t resolve them as two objects,” Keller said.

“So our network will be more sensitive to those close binaries than Hubble is," said Keller.

To form the network, Keller and Buie reached out to the Yuma Foothills Library astronomy group, and to other astronomy organizations up the western part of the country, many of them at local high schools.

The Conways and their team did not capture anything at the first data collection event in June due to something unusual for a mid-summer Yuma night — clouds.

One third of the other communities experienced similar weather troubles. Of the remaining telescopes, 80 percent were able to collect data.

But for this second observation, on the same day the New Horizons mission flew by Pluto, there are clear skies in Yuma.

And while the occultation wasn’t visible through the telescope, the RECON software — which can measure small changes in light — may pick up the shadows in the data.

The RECON team will continue taking data for the next four years, and they expect to gather information about more than 25 objects in the Kuiper Belt. The project is funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

The Arizona Science Desk is a collaboration of public broadcasting entities in the state, including Arizona Public Media.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.