The sun shines harshly behind a saguaro cactus.

The sun shines harshly behind a saguaro cactus.

Heat risk

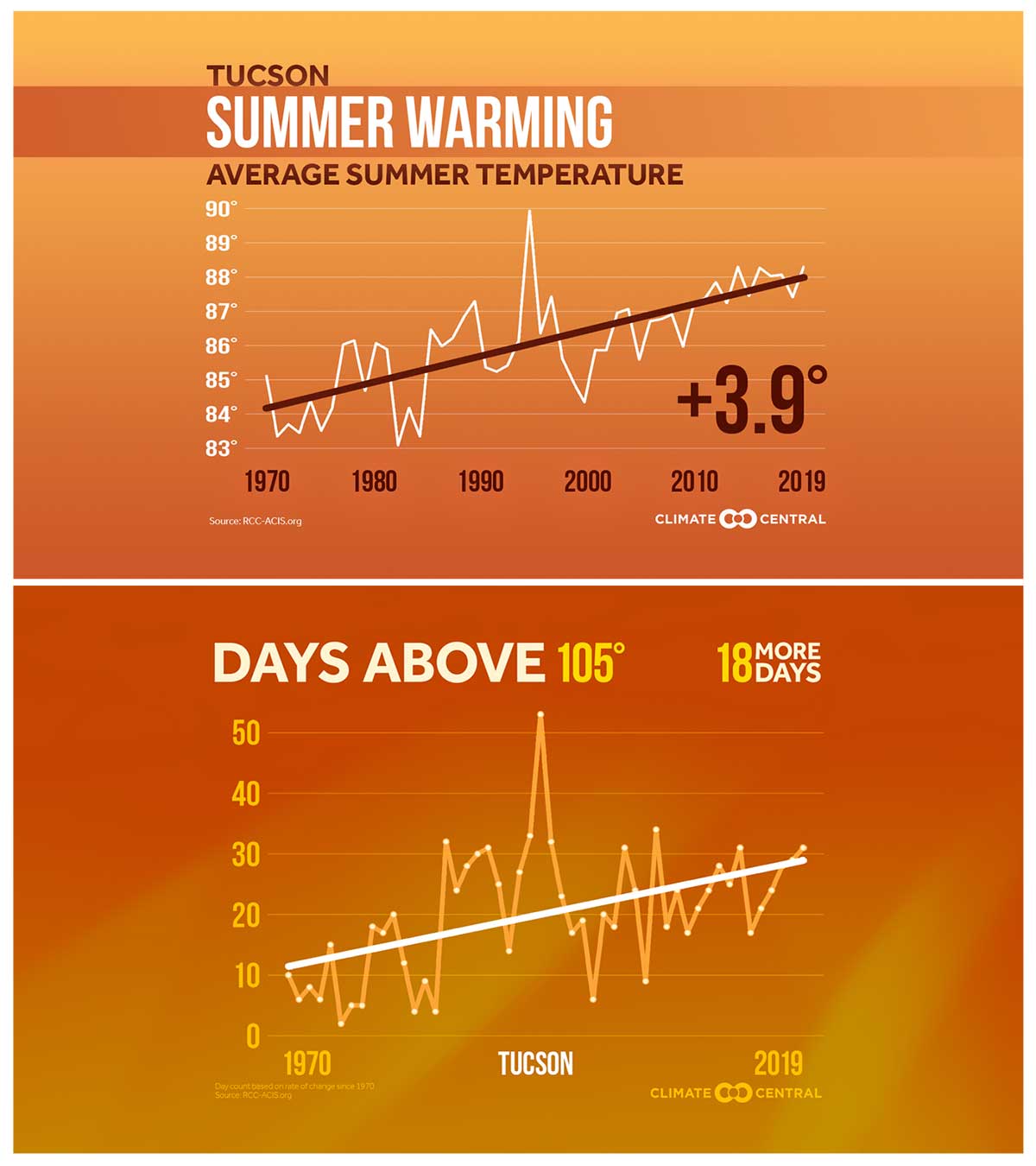

This week the National Weather Service announced August was the hottest month on record for Tucson, following July, which had set the previous record.

Mike Crimmins is a professor and extension specialist with the department of environmental science at the University of Arizona. He spoke about how this year's weather compared to normal and whether this is what people should expect from now on.

One reason the heat seems so unrelenting is because nighttime temperature are also on the rise. “Part of climate change is an increase in overnight temperatures as well,” Crimmins said.

For those who work outside, high temperatures can be particularly dangerous, since there is no relief, Crimmins said. High heat is can increase the risk for people with health problems, including heart and respiratory conditions.

While Crimmins said not every summer will be as grueling as this one, he also stressed the need to take climate change seriously.

This year is on track to be Tucson’s hottest summer on record. The high temps have sent the mercury, and electric bills, climbing. Depending on a person’s situation, heat, housing and the pandemic can result in a stressful combination.

More than 1 million Arizonans receive unemployment benefits. For Arizonans who have lost their jobs due to the coronavirus pandemic, judging which bills to pay first becomes an important task. Electric bills might not be at the top of that priority list, according to Diane Brown, executive director of the Arizona Public Interest Research Group, which advocates for utility ratepayers.

But rising summer temperatures and a reliance on the internet for school and communication make electricity a necessity for all households, including low-income families.

Some social safety nets are already in place to help, but those don't apply to everyone. People who live in mobile homes, which represent about 10% people in Tucson, are particularly vulnerable.

Safety nets like payment assistance programs in Pima County and Tucson are already in place to offset soaring utility bills for low-income households. But most mobile home parks are on a single utility bill. Arizona Association of Mobile Home Owners member Eileen Green said that means those who would otherwise qualify for assistance can’t apply.

"People are just afraid. They don’t know where to turn," Green said. "And unfortunately, our laws don’t protect them that way."

Mobile homes also have a tough time keeping cool air inside due to insulation issues and single-paned windows in older units. For residents with AC units, this can lead to high cooling costs as temperatures rise.

VIEW LARGER A cooling unit sits atop a mobile home in Swan Lake Estates mobile home park on Aug. 31, 2020.

VIEW LARGER A cooling unit sits atop a mobile home in Swan Lake Estates mobile home park on Aug. 31, 2020. Scott Coverdale is the executive director of Community Home Repair Projects of Arizona, an agency offering free repairs to lower income homeowners in Pima County.

He said sometimes his crews will get calls from health care workers with patients already in the hospital for heat related illnesses who can’t be discharged until their cooling is fixed.

“Someone’s in a hospital, they could go home but can’t go home to a house that’s 108 degrees inside,” Coverdale said.

Coverdale estimated his crews have done about 500 repairs this summer. Especially during excessive heat waves, the results of a failed cooling system can be deadly.

Arizona Department of Health Services preliminary data shows a record 283 heat related deaths in 2019. More than half of those occurred in Maricopa County, and 32 occurred in Pima County. Weekly heat mortality reports from Maricopa County suggest the state could be on track to surpass that number this year.

Climate change and urban growth mean a hotter Tucson is inevitable. Some policy makers are working with communities to track the heat and combat its impact. University of Arizona professor and urban heat and governance researcher Ladd Keith doesn’t believe that will make these desert cities unlivable, but it will lay bare the inequalities already in place.

“The thing that concerns me most is the equity component. And the fact that the quality of life and the mortality will be worse off for lower income and marginalized communities,” Keith said.

As the world gets hotter, Keith says it’s important that researchers from areas as diverse as housing, health, planning and transportation continue to work together to bridge the gap.

The pandemic shifted the way Tucson tries to help housing insecure people get relief from the summer heat. This year the City of Tucson teamed up with the Salvation Army of Tucson for Operation Chill Out.

As in years past, the main goal of the project was to provide a place for housing insecure people to hydrate and get relief from the summer heat, according to Tucson Housing and Community Development Director Liz Morales.

Exact services varied by location, but included health and hygiene services, supplies for sun safety, and food.

The Salvation Army followed guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and volunteers screened for symptoms of COVID-19.

Morales says the project served between 500 and 650 people each week.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.