Barbara Tobiasson pictured at her home at the Swan Lake Estates mobile home park on Aug. 31, 2020.

Barbara Tobiasson pictured at her home at the Swan Lake Estates mobile home park on Aug. 31, 2020.

August surpassed July as Tucson’s hottest month on record. Monsoon storms that help temper that heat have been scant. Experts warn this is par for the course in Arizona. For the final installment of our summer heat series, We look at how policy makers, researchers are working with communities to track the heat and combat its impact.

Barbara Tobiasson is used to spending Tucson summers with one swamp cooler at her home at the Swan Lake Estates mobile home park. She’s developed a system.

“What I’ve done is created a little cool zone, and this is where I stay,” she said.

Tobiasson sat on a big living room chair surrounded by two standing fans. She has a double-wide mobile home that’s designed for two swamp coolers, but one of them was broken when she bought the house.

It was too expensive to replace it back then, so these days, half of her house usually stays at or under 85 degrees. The other half isn’t cooled at all.

“The only bad part about it is the kitchen is on that side. So if we want to do any cooking, it gets really warm,” she said.

Tobiasson is a retired University of Arizona employee living on about $600 a month, after expenses. She lives alone and normally takes part in community theater to socialize and also to escape the worst of the heat at home. But the COVID-19 pandemic has changed all that.

“With losing my theater, with the COVID, with the heat, it almost feels like the end of the world,” she said.

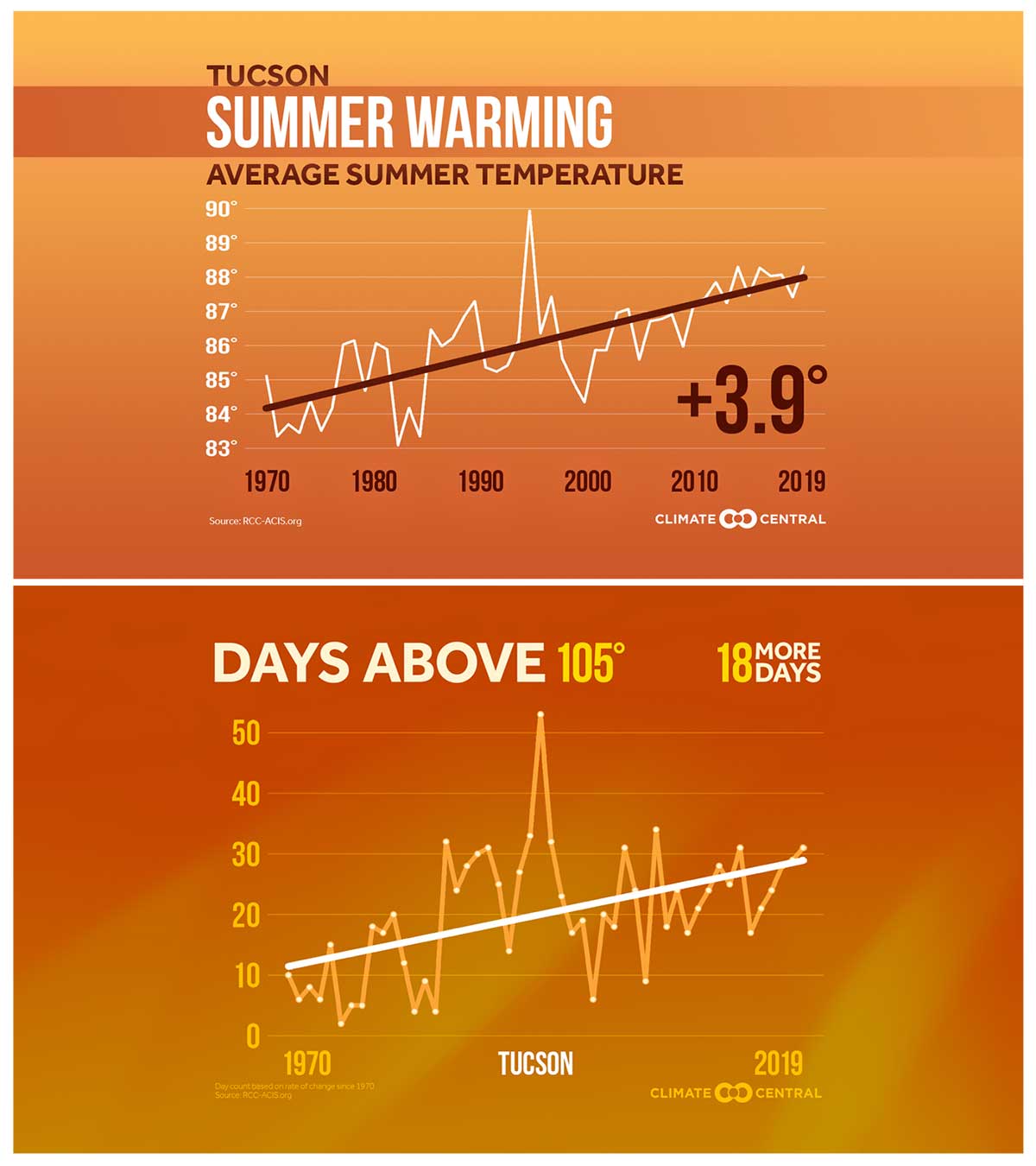

Extreme heat isn’t new in Arizona. But it is getting worse.

This summer has been the state’s hottest on record. The National Weather Service says Tucson clocked four days in August that were 110 degrees or hotter and 26 that were over 99 degrees.

Local resources like the Community Home Repair Projects of Arizona are already on the ground to help residents get through the heat. The agency offers free repairs to lower income homeowners in Pima County.

Scott Coverdale, the agency’s executive director, said repair crews get requests to fix water leaks, failing roofs and plumbing issues. But this summer, a lot of that work has been delayed because crews are busy with emergency cooling issues.

“This summer has been super challenging because of the excessive heat and because of COVID."

He said sometimes, they’ll get calls from health care workers with patients already in the hospital for heat related illnesses, who can’t be discharged until their cooling is fixed.

“Someone’s in a hospital [and] they could go home, but they can’t go home to a house that’s 108 degrees inside,” she said.

Coverdale estimated his crews have done about 500 repairs this summer, the majority for swamp coolers on the fritz. Especially during excessive heat waves, the results of a failed cooling system can be deadly.

Numbers shared with AZPM by the National Weather Service in Tucson show nine excessive heat warnings issued in the Tucson area this year as of Sept. 1, compared with four in 2019 and six in 2018. On Thursday, the office on Twitter warned of more possible heat records urged Arizonans to be careful of the heat in their Labor Day plans.

Arizona Department of Health Services preliminary data show a record 283 heat-related deaths in 2019. More than half of those occurred in Maricopa County, and 32 occurred in Pima County. The most recent report from the Maricopa County Health Department shows 55 confirmed heat-associated deaths in that county so far this year, with 266 more being investigated.

Ladd Keith is an assistant professor of planning and sustainable built environments and the University of Arizona who studies urban heat and governance. He said a combination of factors help Tucson stay a few, crucial degrees cooler than the state's capital.

“Phoenix certainly is larger, they have about 5 million people versus our 1 million,” he said. “They’re also much more developed and those people are spread out over a much larger area, so they have a much more drastic urban heat island effect.”

Keith said a higher elevation and mountainous geography also reduce Tucson’s heat.

The sun sets over Tucson in July 2020, which was the hottest July on record.

The sun sets over Tucson in July 2020, which was the hottest July on record.

Available information around the impact of heat on health is not a standard picture across the state or its urban landscapes. The Arizona Department of Health Services uses vital records to track both heat-caused and heat-related deaths in all the counties, "heat-related" being the catch-all term — in addition to stats like hospitalizations on a sub-county level. The Maricopa County Health Department releases weekly reports on heat mortality, giving a more up-to-date outline of the hot season in the state's much larger metropolitan area. A Pima County Health Department spokesperson told AZPM it typically produces yearly analyses of heat-related deaths, but that process for 2019 data has been delayed this year because of the pandemic.

The Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner releases yearly reports that include heat-caused fatalities. Chief Medical Examiner Greg Hess said that, excluding those who die attempting to cross the border, Pima County's numbers appear to be lower than what might be expected compared with his office's counterpart in Maricopa County, based on population.

Hess says the standard in his office is to only certify heat-caused deaths resulting from hyperthermia, rather than a broader definition that might include heat as a factor and not the direct cause. He doesn’t think that’s the case in Maricopa County.

"It must be more expansive than just pure, heat-caused deaths," he said.

Excluding undocumented border crossers, his office had certified 13 heat-caused deaths this year as of the end of August, and he said the number in recent years is typically somewhere near 10.

Numbers provided to AZPM by the city show 911 calls related to heat for 2018, 2019 and through August of this year. Officials said those calls only include self-reported heat issues, and likely don't capture the range of health events that could result from excessive heat.

Experts warn old age and underlying health conditions like lung and heart disease put people at a higher risk for heat illness and death. Part of that is because older people are less sensitive to symptoms of heat illness and don't regulate heat as well as younger people. UA epidemiologist Heidi Brown said that makes heat impacts harder to understand.

"It’s that chronic condition that the heat sort of exacerbated," said Brown. “I think that makes it more challenging to kind of think about what exactly is the impact of heat."

Brown is co-leading Pima County’s participation in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention program called Building Resilience Against Climate Effects, or BRACE. The initiative works with cities around the U.S. to address heat issues. Brown said it’s been in Arizona for about five years and came to Pima County last year.

Brown and her team have been building on data already collected by the county to address heat related illnesses. She said tracking deaths is just one part of a larger puzzle.

"When we’re just counting [the] number of cases, we get one layer of information,” she said. “But it’s yet another piece of who those cases were, why the cases were where they were and what sort of things were there to not have similar things happening in other areas.”

Experts like Keith say getting the full picture requires researchers from areas as diverse as housing, health, planning and transportation to work together. Heat affects residents in cities like Tucson regardless of whether they end up in a health surveillance system, he said. That means mitigation and tracking efforts have to be multifaceted.

So far, state, county and city entities in Arizona have responded with a range of initiatives to directly or indirectly address the heat and reduce it. Mayor Regina Romero’s office aims to plant 1 million trees citywide by 2030 to mitigate the impacts of climate change and the urban heat island effect. A spokesperson said the office is mapping social and environmental indicators, like tree canopy, to inform that effort.

Meanwhile, cooling centers in both Tucson and Phoenix offer relief to vulnerable populations like those experiencing homelessness. Brown said her team is working with county officials to map and improve the centers, especially as the pandemic has forced operations to change.

Keith said researchers are still working to understand heat impacts and the future of desert cities. That work has brought researchers from areas as diverse as housing, health, planning and transportation together in the last few years.

“As we get to know more about it we need to take a more nuanced approach in understanding extreme heat impacts through quality-of-life impacts, too,” he said. “Things like whether you can go walk your dog when it’s dark, or if your kids can go play in the park.”

Still, climate change and urban growth mean hotter cities are inevitable. Keith doesn’t believe that will make places like Tucson unlivable, but he said it will lay bare the inequalities already in place.

“The thing that concerns me most is the equity component. And the fact that the quality-of-life and the mortality will be worse off for lower-income and marginalized communities,” he said.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.