The Vanishing Vaquita Part 1

The Vanishing Vaquita Part 2

The ship cabin is dark, barely illuminated from the glow of the control board. Jack Hutton sits in front of a blinking radar screen. He's first mate and drone pilot onboard the Farley Mowat, a boat owned by conservation group Sea Shepherd. He's watching the screen for boats.

"We're going to see exactly where they go, and exactly where they stop. Because that likely means that they've put down a net," he says.

Through the wide glass windows you can barely see the surface of the water. We're sailing out in the Upper Gulf of California just past dusk, searching for poachers.

"They try to hide the nets from us," he says, "because each net for them is a huge amount of money. It's up to $3,000 per net. So, they want to hide it from us, to stop us from taking it."

First Mate Jack Hutton sits in front of instruments on the Farley Mowat.

First Mate Jack Hutton sits in front of instruments on the Farley Mowat.Tonight it's quiet — no boats are out. It's late November, and the poaching season hasn't really begun. But in a couple weeks these waters will fill with dozens of boats hunting the endangered totoaba fish, whose swim bladder is in high demand in China as a medicinal food.

"It's like a status symbol almost," Hutton says. "And so, as the totoaba gets extinct, the price for the swim bladders gets higher. And so that's why it's essentially bought and traded like gold."

Fishing for the totoaba has led to the near-extinction of the vaquita marina, a small porpoise native to these waters and nowhere else. To catch the totoaba, fishermen use gill nets, which they often anchor to the seafloor and leave for days, inadvertently killing the vaquita and many other sea creatures in the process.

For the last five years, Sea Shepherd has been working with some local fishermen to collect gill nets around the clock, trying to give the species a fighting chance to recover.

"We are glorified garbage men," Hutton says, "just patrolling up and down, lifting thousands of tons of abandoned fishing gear off the bottom that could potentially kill the vaquita, or any other animals that swim here."

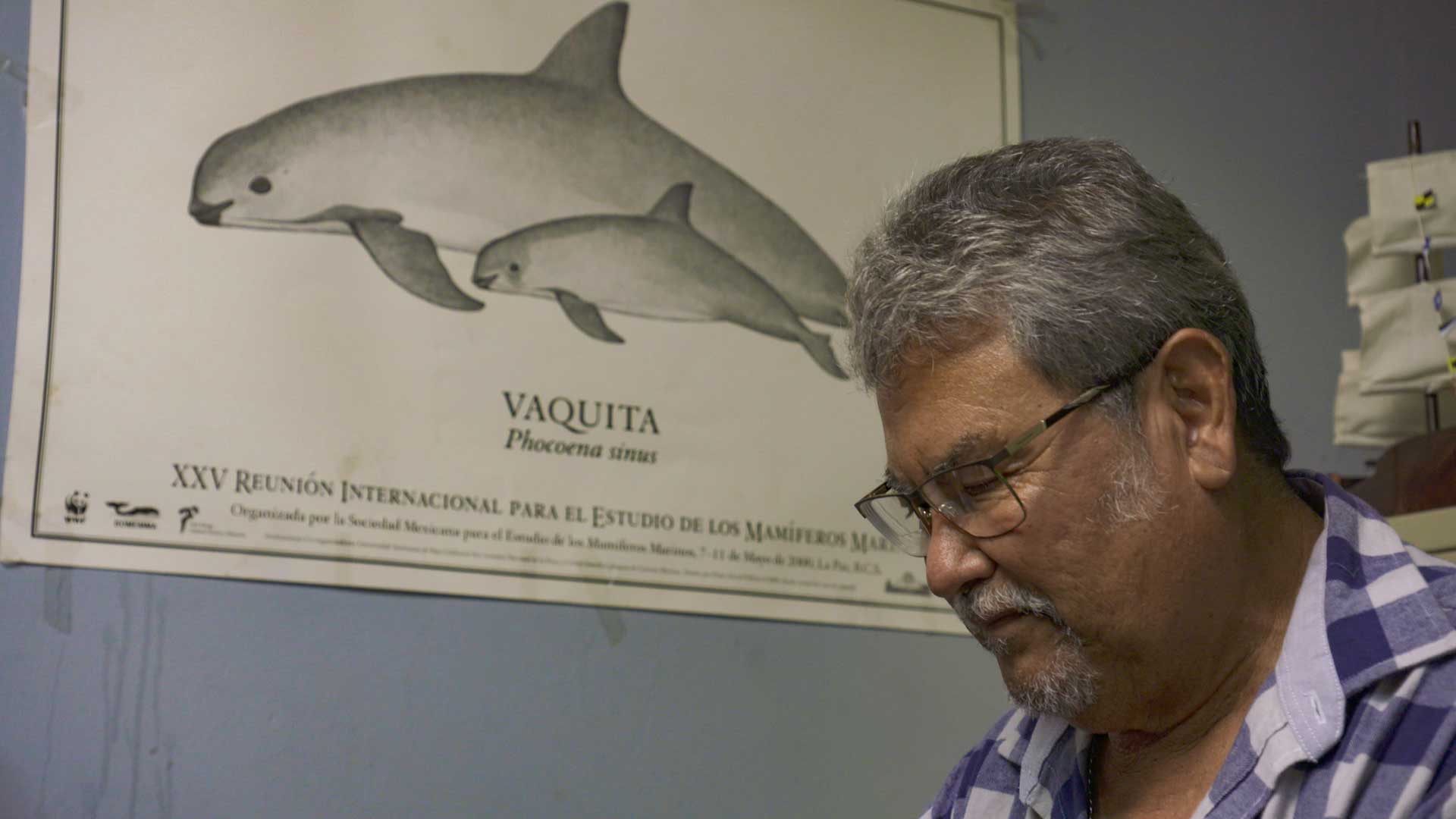

Barbara Taylor, marine conservation biologist, in San Diego.

Barbara Taylor, marine conservation biologist, in San Diego. Barbara Taylor, a marine conservation biologist with NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center, has studied the vaquita for 30 years.

"They're the most beautiful porpoises," she says. "They have beautiful dark eye rings and black lipstick, and they're very slender. So, they're a very endearing animal."

She says the vaquita population was already in decline in 1997, when the first count found 600. In the early '90s, researchers estimated fishermen were killing nearly 80 per year.

The vaquita marina is the world's most endangered marine mammal.

The vaquita marina is the world's most endangered marine mammal."Basically, we knew at that point that the number of animals that were being killed in the fishery could not be sustained by the wild population," Taylor says.

There was a 50% drop between that and the next population count in 2008. Taylor says that around 2011, totoaba fishing took off again, crushing what remained of the vaquitas.

Biologists estimate there are only 6 to 12 surviving vaquitas.

The Mexican government has taken some actions to address the problem, including establishing a vaquita refuge in 2005 and backing research into the species. But Taylor says without a stronger government response to poaching, both active nets and abandoned "ghost nets" kill more vaquitas every year.

San Felipe, in in Baja California.

San Felipe, in in Baja California.Seafood restaurants and colorful mosaics line the boardwalk in downtown San Felipe, Baja California. Fishing is a mainstay of this small town in northern Mexico. La Vaquita restaurant is just a couple blocks over.

A photo of the little porpoise that could be the town's mascot hangs in the office of Ramón Franco Díaz, head of a local fishermen cooperative representing about 570 families.

Díaz says most local fishermen treasure the vaquita. When it rises above the water with its characteristic black-rimmed eyes, he says, "It’s as if it is smiling with you."

"So real fishermen don’t want to harm them. It’s the opposite."

In 2015, Mexico's then-president Enrique Peña Nieto banned gill nets in the vaquita's prime habitat, increased enforcement against poaching and started paying fishermen not to work so the species could recover.

Ramón Díaz in his San Felipe office.

Ramón Díaz in his San Felipe office."So we came to an agreement that we [the fishermen] would leave the sea so that the federal government could clean up the illegal boats," Díaz says.

But by leaving the water, Díaz says they gave the Upper Gulf over to illegal fishing, because the government didn't do enough to get poachers out of the water. As a result, the problem got worse.

He says he's filed numerous complaints with the government to no avail. Then, a year ago, the payments to fishermen stopped.

"So, now we have a serious problem because we don’t have a fishing practice that is permitted, and we also don’t have any compensation," he says.

Last September, Díaz announced his fishermen had no option but to return to the sea to support their families. He says a 2018 U.S. embargo on Mexican seafood caught with gill nets — intended to help save the vaquita – has only made life harder for legal fishermen.

Barbara Taylor agrees. She says the gill net ban also didn't help the vaquita much, because some fishermen struggling financially have been tempted into the illegal totoaba trade anyway. Taylor says the crisis illuminates a larger issue around using gill nets in the Upper Gulf of California.

Luis Albañal Mendoza demonstrates a suripera net.

Luis Albañal Mendoza demonstrates a suripera net."Mexico missed an opportunity to be a world leader in shifting a fishery over from gill nets to alternative gear," she says. Taylor says the government has still not done the necessary work to test, approve and promote alternative fishing methods, like trawl nets, in the Upper Gulf, including creating ways to subsidize or support fishermen for the loss of revenue if other nets prove less profitable.

"Vaquitas and gill nets are completely incompatible. And the fishermen needed to make a living," she says, adding that those close to the issue have known for a long time that developing alternative fishing methods is "really the only way for vaquitas to survive."

Luis Albañal Mendoza is working on it. In his San Felipe office, he pulls a large, thin-strand drift net from a milk crate. He shows off how light the mesh is compared with a gill net.

He's a member of Pesca ABC, a small nonprofit group of fishermen working with the Mexican government to test alternative nets like this one, called a suripera.

"It's vaquita-safe. This works with the current, only with the current," he says.

But Mendoza says using these nets can be nearly impossible because of the sheer number of illegal gill nets clogging the waters. He says even though this net is cheaper than a gill net, it will be hard to convince fishermen to make the change.

"They don't want to switch because it's very effective, the gill nets," he says, meaning more lucrative for fishermen.

Sea Shepherd's JP Geoffroy demonstrates a gill net.

Sea Shepherd's JP Geoffroy demonstrates a gill net.Money is what drives the illegal side of the industry responsible for the vaquita's decline. Poaching for the totoaba is rampant because the fish's swim bladder is highly prized in China and trafficked by cartels.

"It's a lot of money. It's more money than drugs. I mean we're talking about $20,000, $25,000 for one swim bladder," says JP Geoffroy, who leads conservation group Sea Shepherd's program to protect the vaquita.

In port in San Felipe, a black and white flag flaps above the deck of the Farley Mowat, bearing the skull-and-trident logo of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. On the back of the boat, crew members are using a hook to move huge bags of fishing gear they've pulled from the ocean in the last couple weeks.

"All these bags contain all these nets that we remove from the refuge of the vaquita," Geoffroy says. He reaches into one of the bags, making a crunching noise as he lifts out the thick black grid of a gill net, with holes 5 or 6 inches wide.

"This net, they're illegal, they're made for totoaba," he says. "And because the vaquita has the same size as the totoaba more or less, they get entangled here really easy."

Sea Shepherd spends most of its time tracking down and collecting gill nets, which they destroy and recycle for other uses. They recently acquired a net shredder to help that process. But not all locals support Sea Shepherd's work.

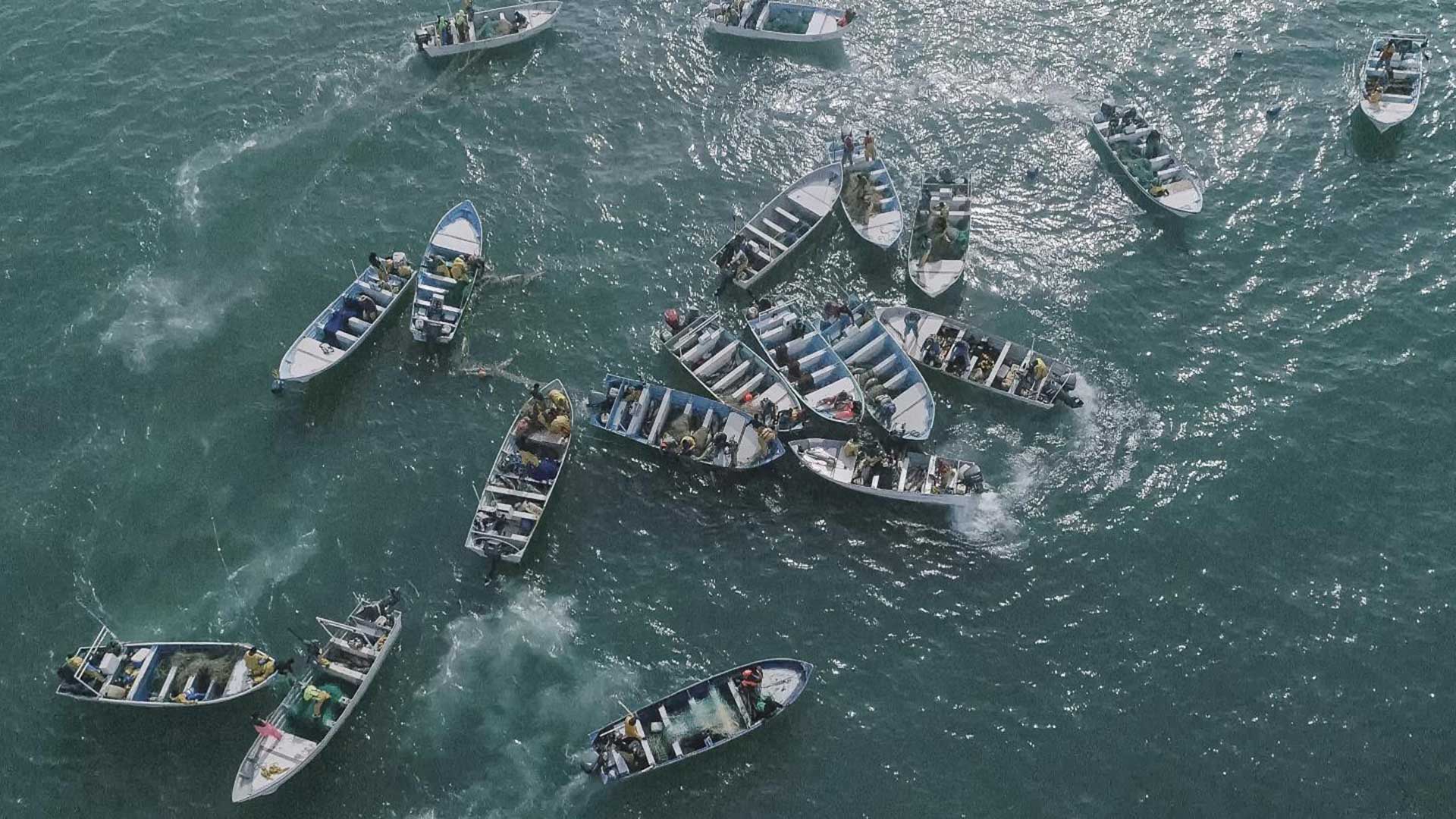

Last week, suspected poachers within the vaquita refuge pursued and fired shots near one of their boats. Members of Mexico's federal police, navy and officials from the environmental protection agency were on board as they have been for years, part of an ongoing partnership between Sea Shepherd and the Mexican government.

A year ago, the Farley Mowat was attacked by more than 50 skiffs, which hurled rocks and molotov cocktails at the ship, breaking its windows and setting the hull on fire, according to video captured by Sea Shepherd.

Despite that tension, Geoffroy says they support local fishermen who just want to do their job.

"We are just trying to work with them and explain to them to at least respect the small rectangle that is the critical area," he says, since that "no tolerance zone" is where the remaining vaquita have been most frequently spotted."

Geoffroy says if they can just protect the remaining vaquita, the species can recover.

Sea Shepherd's Farley Mowat ship.

Sea Shepherd's Farley Mowat ship.A 2017 effort to bring the vaquita into captivity was abandoned after one died during the process. But Barbara Taylor feels confident the species can survive if they’re just left alone.

"They've been a small population for a very long time and they just didn't have much genetic variability to begin with. And yet, they've survived there for 3 ½ million years," she says.

She says the last vaquitas they've seen have marks on their dorsal fins, likely due to entanglement in gill nets.

"And so I think these animals, these last vaquitas, are the survivors. They're the ones that have had bad experience, learned from it, and are extra careful around nets."

Taylor says if they and their calves are protected, they have a real chance. But for now, observers say there’s little evidence that current efforts to stop poaching will be enough.

Reporting for this story was supported by funding from the Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder.

La Vaquita - An Arizona Illustrated Special

Producer Vanessa Barchfield takes us on a journey to the Sea of Cortez where the most endangered marine mammal on earth is fighting for survival against overwhelming odds.Conservationist ship attacked in endangered vaquita refuge

The crew patrolling to protect the endangered porpoise in the Sea of Cortez came under fire by suspected poachers.Poachers swarm vaquita refuge ‘like never before’

A conservationist said the number of poachers in the endangered porpoise's habitat — casting nets for a fish called the totoaba — is unprecedented.Conservationists: Mexican government failing to protect vaquita

They say Mexico has not been able to curb illegal fishing in the Sea of Cortez that threatens the nearly extinct porpoise.Body of Dead Vaquita Porpoise Found as Report Says Only 10 Left

The critically endangered marine mammal found in the Sea of Cortez is in danger of extinction due to illegal fishing nets.The Plight of Vaquita in the Sea of Cortez

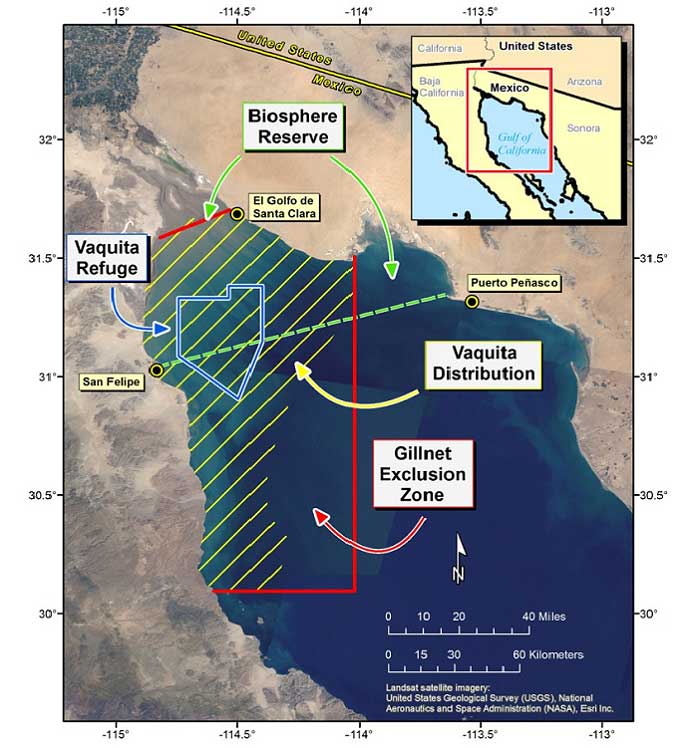

Also on Arizona Spotlight: A deadline looms for a comprehensive water plan in Arizona, and how a "ballot brunch" can help attendees become better voters. VIEW LARGER 2016 map showing vaquita distribution and refuge in the northern Gulf of California.

VIEW LARGER 2016 map showing vaquita distribution and refuge in the northern Gulf of California.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.