‘A safe haven, a home’

O’odham communities fight against border wall construction at Quitobaquito Springs.On a warm day in February, Amber Ortega stood in a dirt parking lot at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and stared up at the new, 30-foot steel bollard wall marking the U.S.-Mexico border ahead. A pair of wooden construction stakes topped with pink tape swayed in the wind, and a line of shining metal stadium lights towered past the top of the wall.

It was the first time Ortega had seen the finished wall.

Ortega was arrested along this stretch last September by National Park Service officers for trying to physically stop construction by blocking machinery. Park officials closed the road here for months amid similar protests. Ortega and another Hia C-ed O’odham activist were the first of more than a dozen people arrested in connection with the protests.

“The footprints and handprints and bones of our ancestors were disturbed,” she said. “The land that was walked on for generations will no longer be the same…the sky will never be the same... due to this border wall.”

Contractors hired by the Department of Homeland Security finished walling off nearly 30 miles of borderland inside Organ Pipe last winter, part of more than 450 miles of wall the Trump administration installed by the time President Joe Biden took the helm this year.

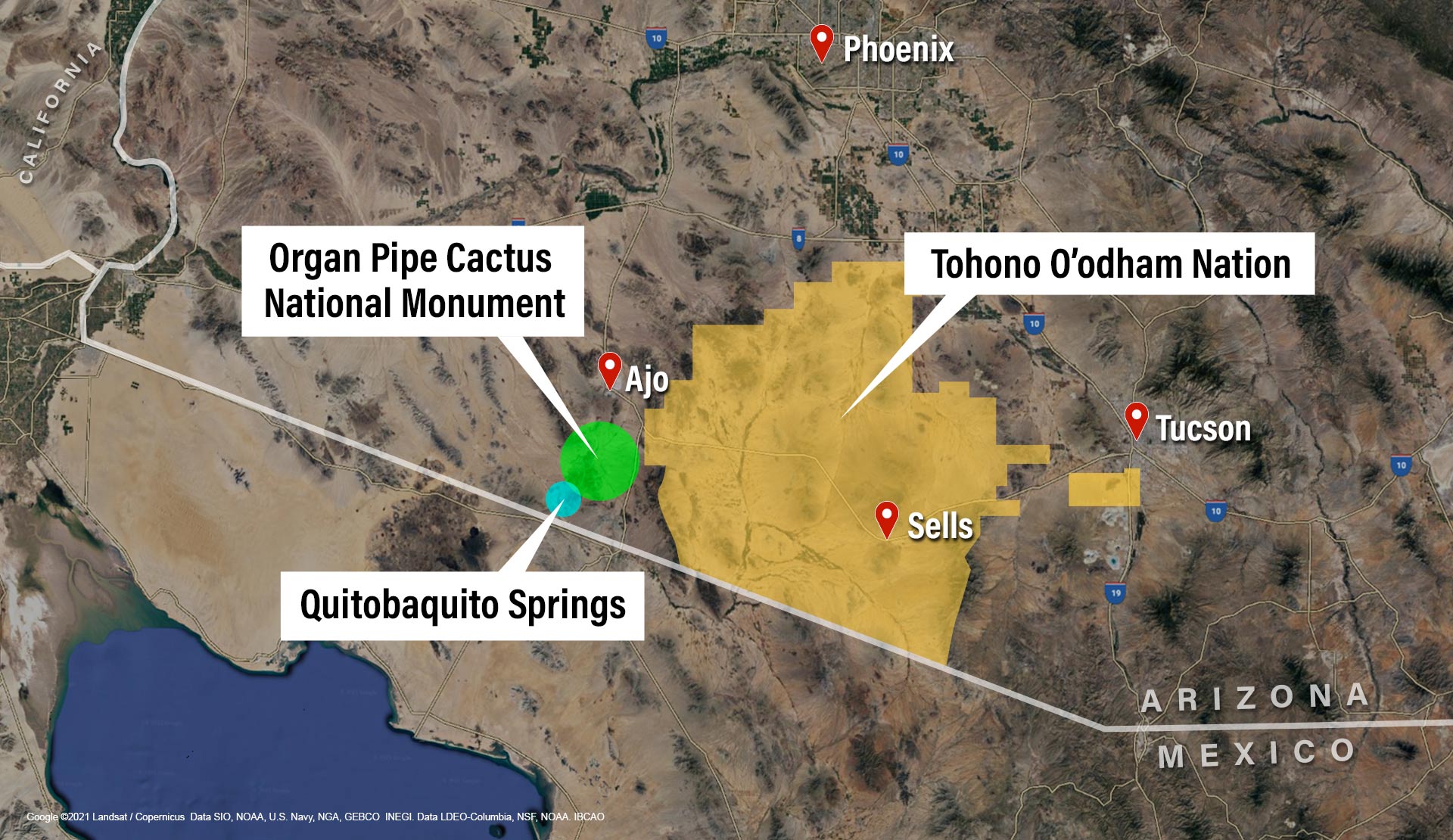

Ortega grew up east of Organ Pipe in the Tohono O’odham Nation, which is roughly the size of Connecticut and runs along the border for about 60 miles. Ancestral O’odham land extends into northern Mexico and across swaths of central and southern Arizona, including Organ Pipe.

Last year, Ortega and others from O’odham communities began mounting a fight against wall construction when contractors began closing in on Quitobaquito Springs, a rare freshwater source and manmade pond along the border in Organ Pipe.

Map of the Tohono O’odham Nation and Quitobaquito.

Map of the Tohono O’odham Nation and Quitobaquito.‘A safe haven’

Today, Quitobaquito is a cherished site for tourists visiting the Sonoran Desert and ecologists studying it, a verdant patch that is the sole U.S. habitat for endangered species like the Sonoyta mud turtle and pupfish. But Ortega said long before the park or the border existed, the site was a homestead to Hia C-ed O’odham families, including her own.

“This place has a strong history of being a safe haven, a home,” she said.

Unlike the Tohono O’odham, Hia C-ed O’odham are not recognized by the U.S. government, and they don’t have protected tribal land. Families lived at Quitobaquito until the 1950s, when the land was purchased by the National Park Service.

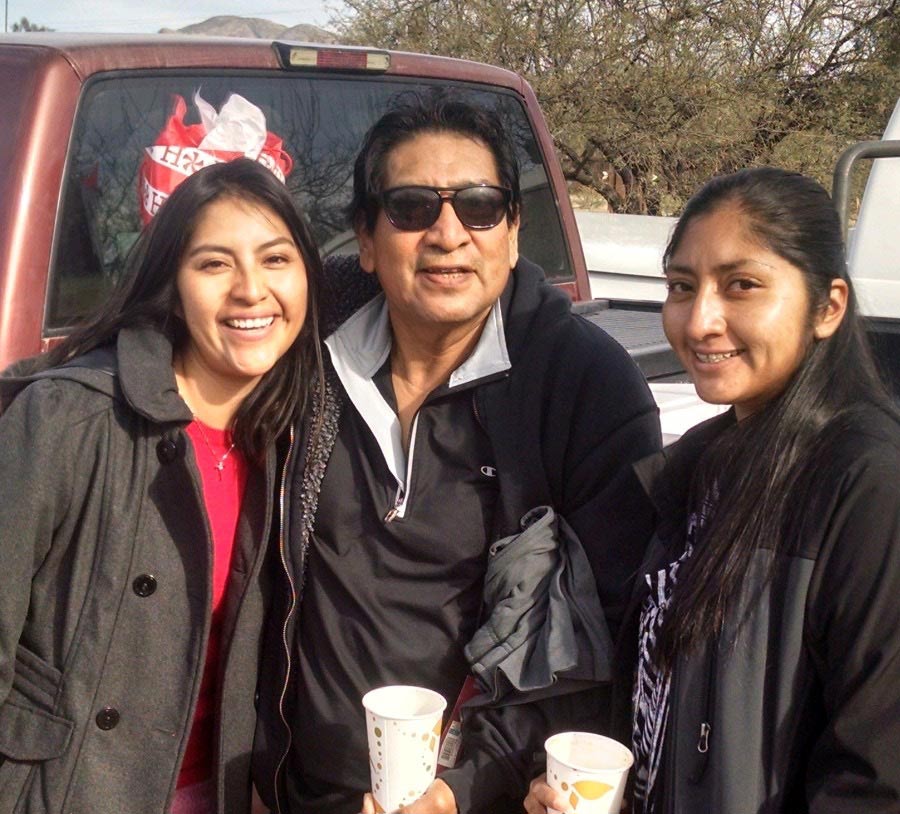

But growing up, Ortega said she didn’t know about this part of her family history until her father, Melvin Ortega, began filling in the dots for himself as a filmmaker.

Melvin spent years chronicling O’odham culture in the Tohono O’odham Nation and throughout Arizona. Ortega said she was introduced to a lot of history through his work. When he died a few years ago, she returned to the Organ Pipe area to pick up where he left off.

“He made a video about the Hia C-ed O’odham, and he was able to interview his dad, and show me his father for the first time,” she said. “It was almost like ‘look, here’s a part of your history... here’s where your relatives are buried. And it wasn’t a cemetery he showed us, it was Quitobaquito.”

Construction continues

By the summer of 2020, border wall construction was well underway in the park. Contractors were using dynamite to blast through terrain, digging trenches, widening roads and pumping groundwater to mix cement. Customs and Border Protection said it would need 84,000 gallons of water per day but agreed not to drill within five miles of Quitobaquito.

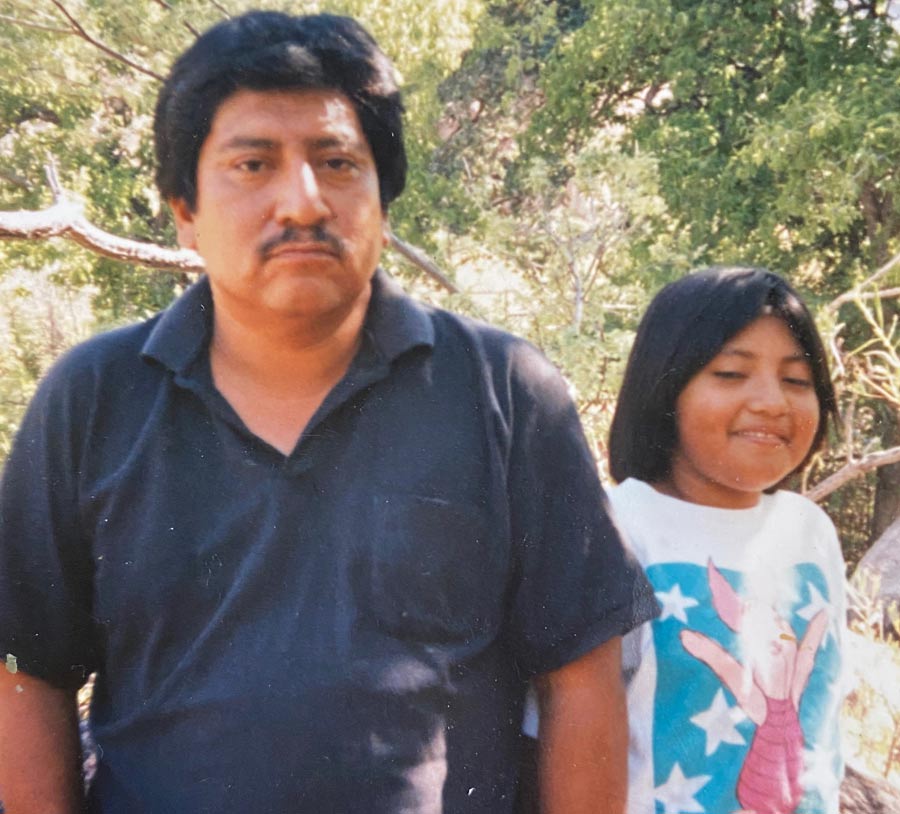

Lorraine Eiler's great grandfather was one of several Hia C-ed O'odham who used to live at Quitobaquito Springs.

Lorraine Eiler's great grandfather was one of several Hia C-ed O'odham who used to live at Quitobaquito Springs.Still, O’odham community members say they watched the site begin to change. Cracked mud flats appeared across most of the pond’s surface and in mid-July, USGS registered a record low spring flow of 5.5 gallons per minute.

Park service officials said the change was due to leaks in the pond’s lining, long-term drought and years of agricultural pumping in neighboring Sonora.

One scorching afternoon last September, Lorraine Marquez Eiler, a Hia C-ed O’odham elder whose family once resided at Quitobaquito, sat on a bench beside the pond after a cross-border ceremony. She said it’s hard not to see a connection between construction activity and Quitobaquito’s decline.

“Why did all of the sudden, when the fence started coming nearer and nearer, and you have blasting, and you have over 100 trucks going through here, and then they have to dig and pull water out so they can do their cement,” she said. “They’re telling us it has no effect whatsoever. But why in the short amount of time when they started from that hill, did this happen here?”

The border under Biden

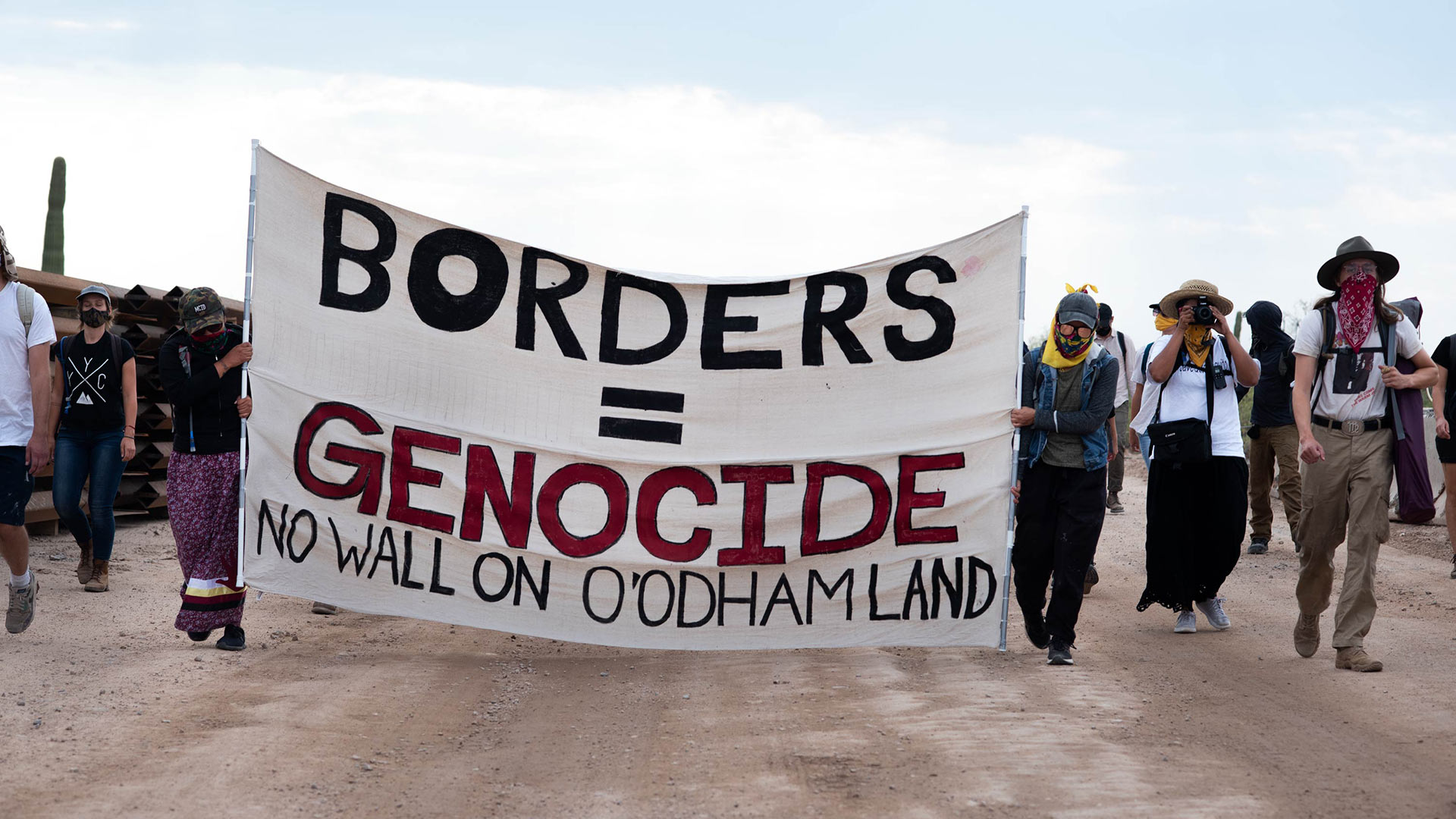

TOP: Indigenous-led protesters walk along a construction line in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Sept. 2020.

TOP: Indigenous-led protesters walk along a construction line in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Sept. 2020.

BOTTOM: During the last of two physical encounters with Border Patrol agents and park officers, a protester is pulled from a fallen human chain by a National Park Service officer at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument on Sept. 21, 2020.

Indigenous-led demonstrations against the wall continued for months. First along the construction line in front of Quitobaquito and then, when park service officials closed the route to get there, in front of Border Patrol checkpoints along the highway nearby. Ortega remembers the day of her arrest clearly.

“We planted ourselves on both sides of the road and we sang,” Ortega said. “We took turns praying and singing and we took turns explaining ourselves, who we were, and what this land meant to our people.”

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden issued an executive order that temporarily halted construction of his predecessor’s border wall. But questions remain about what comes next.

Environmental and cultural groups say they want a permanent end to the project, and are pushing to remove segments in sensitive areas, like Quitobaquito, altogether. Eiler and other local advocates are also working with NPS to restore the site. They’ve raised $250,000 to repair leaks in the pond and make other changes.

But so far, the Biden administration has not publicly supported taking down anything that’s already built, and hasn’t said whether contractors will be allowed to resume work.

Ortega’s case is pending in federal court. She faces two federal misdemeanor charges of “violating a closed order” and “interfering with a federal function.” She said she hopes the charges will be dismissed under the new administration. But she said that day felt like the continuation of a fight her father started, regardless of what comes next.

“Accountability was a goal, and I knew that there will be consequences,” she said. “It does feel good to say that for that day, we were able to stop construction, that day we were able to stop the desecration of our sacred site. That day we were able to be Hia C-ed O’odham.”

Quitobaquito pond.

Quitobaquito pond.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.