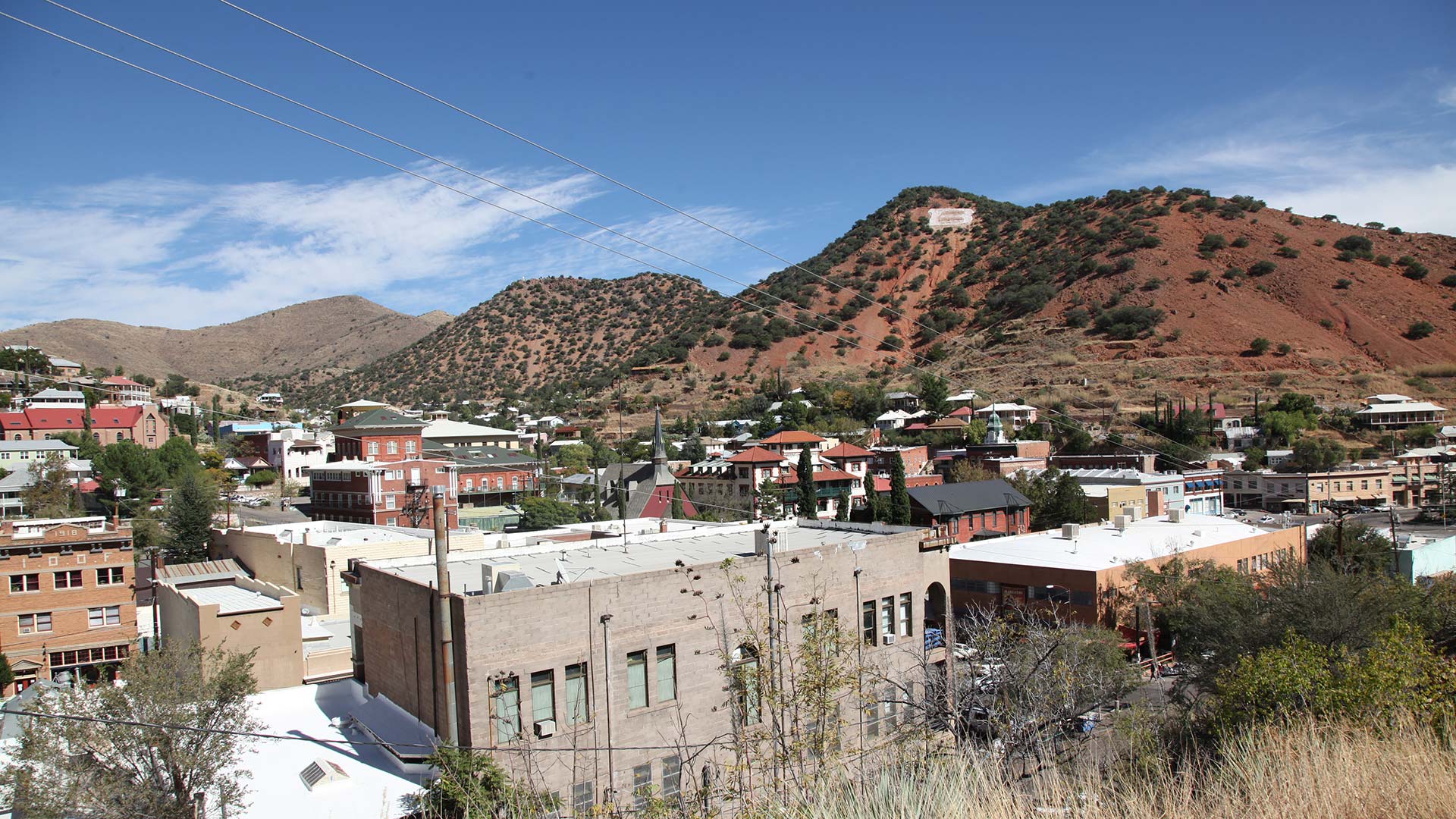

A view of downtown Bisbee.

A view of downtown Bisbee.

The Buzz for July 29, 2022

In the summer of 1917, unionization was the talk of many mining communities in Arizona.

Members of the Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the IWW or the Wobblies, had arrived in the state and began organizing strikes at some mines.

By July 12, mine company executives came up with a plan to break unionization attempts that culminated in an historic event known as the Bisbee Deportation.

But the experiment with exiling pro-union miners and residents didn't start in Bisbee.

The first try at a deportation happened days earlier in the smaller mining town of Jerome.

Jerome, AZ as viewed from the Douglas Mansion.

Jerome, AZ as viewed from the Douglas Mansion.

America had entered World War I, leading to increased demand for bullets and military hardware, both of which utilized plenty of copper.

And rural electrification efforts also increased demand for copper wire.

The result, the price had doubled in about a decade.

But while it was boom times for mining companies the work life of a miner was quite different.

"[They worked] 12 hours a day, 6 days a week, minimal pay, hazards, underground, lot of accidents," said Jerome Historical Society General Manager Jay Kinsella.

And it wasn't easy work, according to Henry Vincent, a tour guide at the Jerome State Historical Park Museum, which sits in the mansion that was built by 'Rawhide' Jimmy Douglas, who owned one of the mines in Jerome.

"A lot of the work that went on underground. there was certainly mechanization as that became increasingly popular, but there was a tremendous number of ore buckets that were loaded with a shovel," he said.

The Douglas Mansion, home to the museum at Jerome State Historical Park.

The Douglas Mansion, home to the museum at Jerome State Historical Park.

Once men were off of work, low wages and the cramped conditions of a boomtown meant they often slept in a room where they shared a bed with someone working the opposite shift as they did.

Word eventually got out that miners were unhappy, and wanted the length of their shifts nearly cut in half while also seeing a near-doubling of their wages.

Plus they wanted safer conditions, such as two men working on dangerous equipment such as a pneumatic drill known colloquially as 'the widow maker.'

On July 7th, 1917, one of the town's newspapers, the Jerome Daily News, reported that a group of miners gathered to consider a strike.

"And the result was 471 votes against a strike and 194 in favor of the strike," said Kinsella, noting that it was a blow to the morale of those men who voted for a strike and they became increasingly boisterous.

"The mining company executives saw the handwriting on the wall. They did what they could, but they needed to be, back then, as politically correct as they could be," he said.

Instead of trying to break the strike themselves or hiring someone to break the strike as other industries did, they riled up the anti-union workers and residents of Jerome.

On the night of July 9th, people who didn't want the mine to shut down were supplied shovels, ax handles, and other items to use as weapons.

The next morning, 250 armed men showed up for what, according to historian John Lindquist in a 1969 article from the Journal of the Southwest, they called "clean up duty."

"All hell broke out, said Kinsella. "There was face to face confrontations, violence, beatings on both sides."

Lindquist writes that they started at 6:00 in the morning, and rounded up about 100 men by 9:30 that morning.

Between 63 and 67 men–depending on the source–were loaded into four cattle cars that had shown up on a mine-owned railroad line near the mine.

The mining companies claimed they were not the instigators, but only supplied the cattle cars.

Plus, the mine's owners, William Clark and 'Rawhide' Jimmy Douglas spend much of their time elsewhere, as they owned multiple mines across the country.

"But I tell you, they knew exactly what was happening in Jerome even though they weren't here," said Kinsella.

"That was kind of the tone of how you met labor organization in those days, and I'm not saying it was right," said Vincent. "But the original dry run of kicking the Wobblies out of town came here in Jerome, where they were loaded onto cattle cars and shipped out."

The men's first stop was Needles, California, but locals prevented the train cars from being unloaded, so the cars headed eastward back to Kingman, Arizona.

"It basically boiled down to a concern that the miners had, a concern that the mining company officials had, and the worst of times to wage this concern, which was the start of World War I," said Kinsella.

Days later, mining company Phelps Dodge was again dealing with miners who were displeased with their working conditions and threatening a strike, this time in Bisbee.

They saw the action taken in Jerome as a possible plan of action to break this labor organization movement.

Charles Bethea was born and raised in Bisbee, and is a local historian.

He says the roundup ended at a landmark that still stands today, Warren Ballpark.

VIEW LARGER Warren Ballpark in Bisbee, AZ. July 2022

VIEW LARGER Warren Ballpark in Bisbee, AZ. July 2022 "On July 12, 1917, the deportees were rounded up starting in Upper Old Bisbee, were marched four miles from downtown Bisbee, and they were staged in this park."

The most notable difference between the two events was the scale. The Bisbee Deportation was about ten times the size of Jerome's.

"There were about 2,000 deputies, temporary deputies, and vigilantes to round up 2,000 people."

The action in Bisbee was also notably more official.

"The most active one involved was John C Greenway, who was the head of Calumet in Arizona. And he was pleading with these guys, 'Come on, just give it up and you can go back to work and this will be over with."

About 800 men listened to Greenway's pleas. The final total loaded onto the train fell between 1,100 and 1,200.

Warren Ballpark in Bisbee, AZ. July 2022

Warren Ballpark in Bisbee, AZ. July 2022

Cochise County Sheriff John Wheeler also took part, deputizing men and overseeing the operation from a car that he borrowed from the local Catholic priest while toting a belt-fed machine gun.

Many of the anti-union men were armed with weapons.

In a 1971 oral history recording hosted on the Bisbee History and Mining Museum, Bisbee resident Walter Brockbank recalled that guns were common around the city at that time.

"Just prior to this country's involvement in the war in Europe, the Mexican bandit by the name of Pancho Villa had made a raid into the United States near Columbus, New Mexico. At that time, there was very little military protection along the border, so many towns along the border fearing other such raids began to organize home guard duties, which we did here in Bisbee, having three companies of about 300 men each."

Those groups were able to purchase surplus guns and ammunition from the Spanish-American War. Brockbank went on to note that these groups were not active participants in the deportation, though many of men in them may have participated.

Brockbank himself did not take part on either side. As a fellow mine employee–he worked in the mechanical rooms that allowed the mines to function–he sympathized, but refused to strike due to the danger stopping those machines would have brought.

Another mechanical room worker, Dan Kitchell, expressed similar sentiments when recalling what he saw in another oral history while also noting the level of organization.

"I asked Jimmy McDonald, who was a Deputy United States Marshall, 'what's this all about?' he said, 'I don't know. I can't get word from my office. the wires have been cut.'"

"[The mines] owned the hotel," said Charles Bethea, "And the telephone switchboard was in the hotel, and on the morning of deportation, they shut it down. So nobody could make a phone call, nobody could send a telegram from the telegraph office."

Bethea expressed amazement that only two men were killed that day, both on opposite side of a conflict in an area of town known as Jiggerville.

The round-up stretched beyond miners and included those who were openly sympathetic to their cause.

That included Mike Pintek, a Croatian immigrant who owned a store and a taxi service in town.

"Mike had tuberculosis," said Bethea. "Katie Pintek, his wife, she went to Dr. Nelson Bledsoe who was the chief surgeon at the Calumet hospital, who was carrying weapons and had cartridge belts."

She was eventually successful in convincing the men not to load her husband on the train. But harassment by their neighbors led to Mike Pintek hiding out in Mexico for more than a month before returning home.

His son John, seems to have been shaped by the 1917 events. He went to law school and returned the youngest County Attorney in Arizona history, he was 25 at the time.

After serving in World War II, John Pintek went into private practice. His obituary calls him a fighter for social justice including miner's rights and benefits for miner's widows and children.

And the family legacy didn't end there, his son John was Cochise County Sheriff for one term starting in 1993.

The Pinteks were fortunate that their patriarch was able to return home eventually. That was not the case for many families.

Bethea says many of the men were eventually allowed back, but only to pick up their families and property.

"Some of the women, they actually divorced the husbands who they loved in order to be able to survive because they had to marry somebody else," said Bethea.

The train left Bisbee before noon, headed east toward New Mexico.

"There was an attempt made to drop them off in Columbus when the train got there about 9:00 at night," said Mike Anderson, an historian who lives in Bisbee and has spent the past few years studying what happened after the deportation.

"The Columbus authorities informed the train crew and the vigilantes that, whatever authority you had to do this in Arizona, you have none in New Mexico. You need to take this train back to Arizona immediately, and if you don't, we're going to arrest all of you for kidnapping."

The train did return to Arizona, but not before disconnecting the cattle cars with the deportees in a rail siding in Hermanas, New Mexico.

The White House eventually sent the U.S. Army to pick up the men and take them to a camp in Columbus. From there, many of the men began seeking justice.

Anderson said the men filed kidnapping charges against those involved.

"How do you process hundreds and hundreds of kidnapping trials? The Cochise County Attorney decided to try one man, Harry Wooten. If the jury convicted him, they'd start in on the others."

But Wooten was found not guilty. The jury cited the law of necessity.

"Now, I challenge you to find an Arizona Revised Statutes where the law of necessity is, because it ain't in the law books," said Anderson.

The deportees eventually filed a class action lawsuit against the mining companies and others involved. That case was settled out of court.

The deported men fanned out, with some eventually making it back to Bisbee. Anderson has tracked a handful to graves in Evergreen Cemetery.

"They picked up their lives and they went on with it, and that was one of the most interesting things to me. These were not men who suffered calamity and just fell to pieces. they were tough, considering that 80% of them were immigrants, they'd already gone through great hardship."

The story of the deportation was buried over the years, especially when it came to teaching future generations in Bisbee, like Charles Bethea who graduated high school in the late 1960s and his sister who graduated in the early '70s.

"She went to [Northern Arizona University]. and she was taking an Arizona history class as a freshman. The professor was talking about the history of copper mining, and he mentioned the story of the deportation. And she said, 'Excuse me, what are you talking about? i'm from Bisbee. That did not happen' And he started to laugh and said, "If you're from Bisbee, then of course you don't know that it happened."

Arizona's copper industry was eventually unionized, and in the early 1980s was a part of a major labor battle when unionized miners again struck against phelps dodge.

That strike became national news when, after a five-year battle, it led to the largest mass union decertification in u-s history.

"At the end of the day, this is not a story about copper," said Bethea. It's a story about people and the way power and money affect people's lives. and for those men to just have been dumped off into anonymous history is a criminal thing to me."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.