Pat Shoneck and Eileen Green ride in a golf cart at the Swan Lake Estates mobile home park, a 55+ park where Shoneck lives.

Pat Shoneck and Eileen Green ride in a golf cart at the Swan Lake Estates mobile home park, a 55+ park where Shoneck lives.

On a cooling day at the end of August, Pat Schoneck and Eileen Green drove a golf cart through neat rows of metal houses, pointing out boxy air conditioning units sticking out from windows and swamp coolers on roofs.

They were there to show me how mobile home residents were dealing with the Arizona summer. That day we visited Swan Lake Estates, an east Tucson retirement park where Schoneck lives.

"Now, on this street there are homes that are from the '60s, this green and white one here, see they both have these trailer hitches," Schoneck said, pointing out an aging metal point at the front of the unit.

Schoneck said there are about 270 homes in Swan Lake, some built in the 1960s and 1970s, others as recently as 2013.

Mobile home residents face unique challenges, from heating and cooling to maintenance and rental agreements. As members of the Arizona Association of Mobile Home Owners, those are the issues Schoneck and Green are hoping to tackle.

Before the pandemic stalled travel, the duo would visit three to four parks in a day around the state. They give informational sessions about mobile home resident laws and protections, respond to complaints at parks, and recruit new members.

People all over Tucson are struggling to pay the bills this summer thanks to COVID-19 job losses. But Schoneck said that’s a problem mobile home residents face even in normal times. Insulation issues and single-paned windows in older units make it hard to keep the cool air in. Many rely on swamp coolers and window AC units.

"Many of [the units here] have pretty much a flat roof and they don’t have much insulation in them, and so those people are paying good sized electric bills," she said. "People are pretty much shut in with this pandemic."

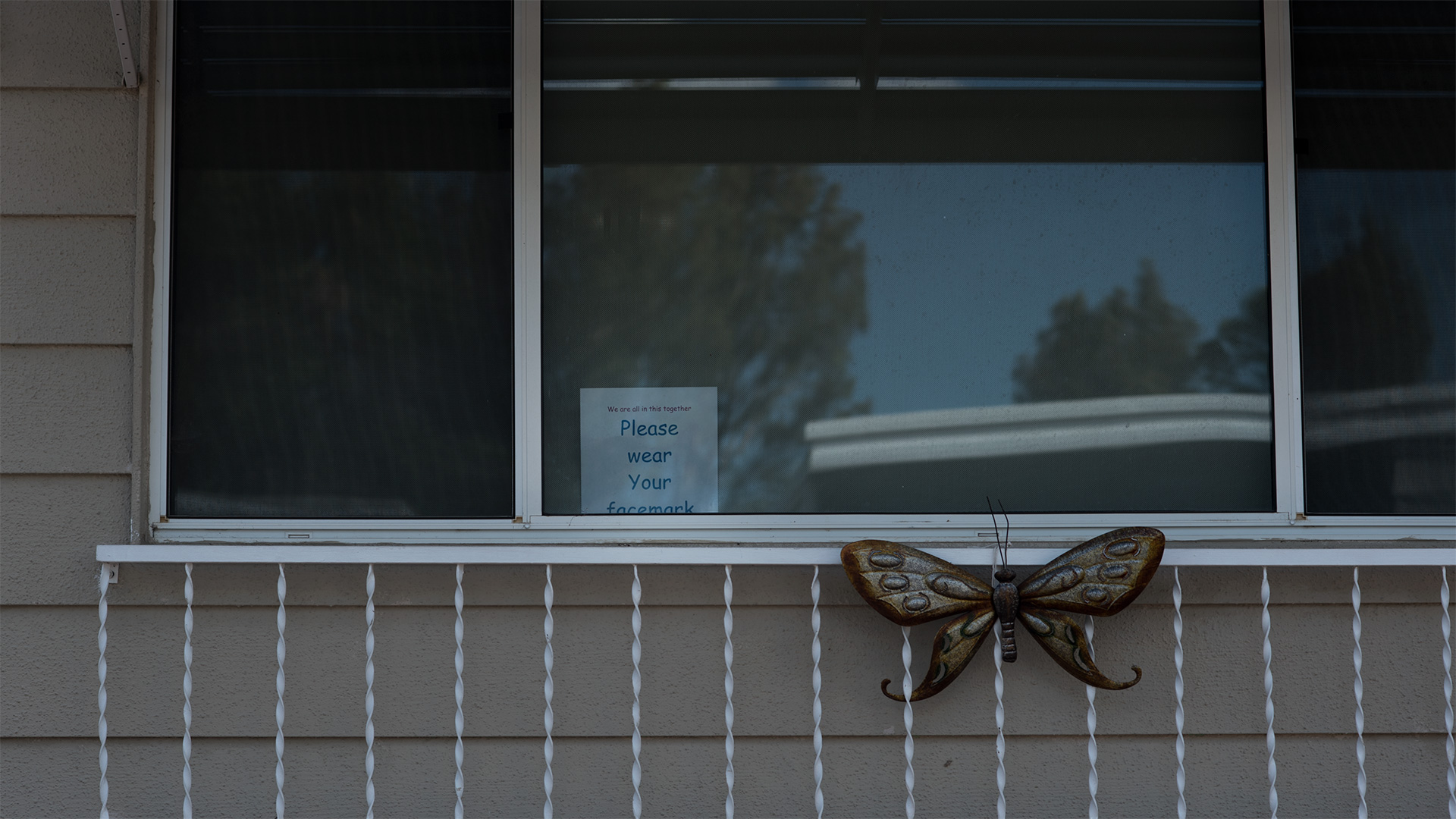

VIEW LARGER A sign reading "We are all in this together. Please wear your facemask," is seen in the window of a mobile home at the Swan Lake Estates on Aug. 31, 2020.

VIEW LARGER A sign reading "We are all in this together. Please wear your facemask," is seen in the window of a mobile home at the Swan Lake Estates on Aug. 31, 2020. Schoneck said some residents here are paying as much as $300 a month for air conditioning just to keep their units below 90 degrees.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has people spending more time at home — all while Arizona is dealing with the record summer temperatures. According to the National Weather Service, Tucson saw a record daily high of 105.7 degrees in August. That same month, Phoenix saw a record 50 days of 110 degrees or higher.

In July, Tucson broke its record for hottest recorded single month. Then it did it again in August.

Safety nets like payment assistance programs in Pima County and Tucson are already in place to offset soaring utility bills for low-income households. But most mobile home parks are on a single utility bill. Green said that means those who would otherwise qualify for assistance can’t apply.

"People are just afraid. They don’t know where to turn," she said. "And unfortunately, our laws don’t protect them that way."

Swan Lake has its own payment assistance program set up by the owner. But it’s is an upscale, retirement park outfitted with clubhouses, pools and lush greenery around a man-made lake. Green said it’s one of more than 600 parks scattered around Tucson. Many house low-income families.

"It’s 10% of all housing in metro Tucson and 10% of the population," said Mark Kear, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Geography, Development and Environment whose work has focused on mobile homes. "So you’re talking about 100,000 people living in manufactured housing."

VIEW LARGER A cooling unit sits atop a mobile home in Swan Lake Estates mobile home park on Aug. 31, 2020. Shoneck said the park has around 270 homes that vary in age and cooling system. Many still have their original swamp coolers.

VIEW LARGER A cooling unit sits atop a mobile home in Swan Lake Estates mobile home park on Aug. 31, 2020. Shoneck said the park has around 270 homes that vary in age and cooling system. Many still have their original swamp coolers. Kear said mobile homes began appearing at large in Tucson in the 1970s, mobile homes offered a low-cost housing solution without the property taxes.

"People could set up parks, they could put their manufactured home on a plot of land and not pay really anything in the way of taxes other than vehicle registration," he said. "So you had people living on a home that cost them basically $5 a year in taxes."

Now the structures are a bastion of affordability for families who don’t have other options.

"There’s nothing inherently problematic with housing built in a factory," he said. "But the way it’s lived in and experienced by residents often falls far short of that promise."

Kear said the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development regulated how mobile homes were built when it established a national code for them in 1976, but many of the units in Tucson were built before that time are not necessarily up to code.

He said issues also arise with how renting occurs. In addition to renting or buying the mobile home itself, residents often pay an additional lease for the land underneath it. Kear said that means they're vulnerable to being displaced if the park is closed.

Green and Schoneck said closures like that happen all the time. Conditions vary widely between parks, and it's difficult to keep track of how residents are coping.

"It’s been hotter, way hotter [this summer]," said a resident from a low income park just down the road from Swan Lake. "I have two [wall] AC units in the house, and it stays 80 degrees, 80 or 90 degrees. It’s just miserable inside."

This kind of heat isn't just miserable — it can be deadly. Arizona clocked a record 283 heat-related deaths last year, toppling record-breaking numbers in 2018 and 2017.

The overwhelming majority of those deaths last year occurred in Maricopa County. But Green and Schoneck said looking at the numbers makes them sure similar problems are happening in Tucson.

"Nobody's looking at it and nobody marks it as heat-related death," Green said.

The Arizona Department of Health Services issues reports on heat-related and heat-caused deaths in Pima County, as it does for every county in the state. In an email, the Pima County Health Department said it tracks heat illness and death data based on hospital discharges.

This is the second in a three-part series looking at the risks of severe heat and housing during the pandemic. The next story looks at how researchers, community leaders and residents are addressing the issue.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.