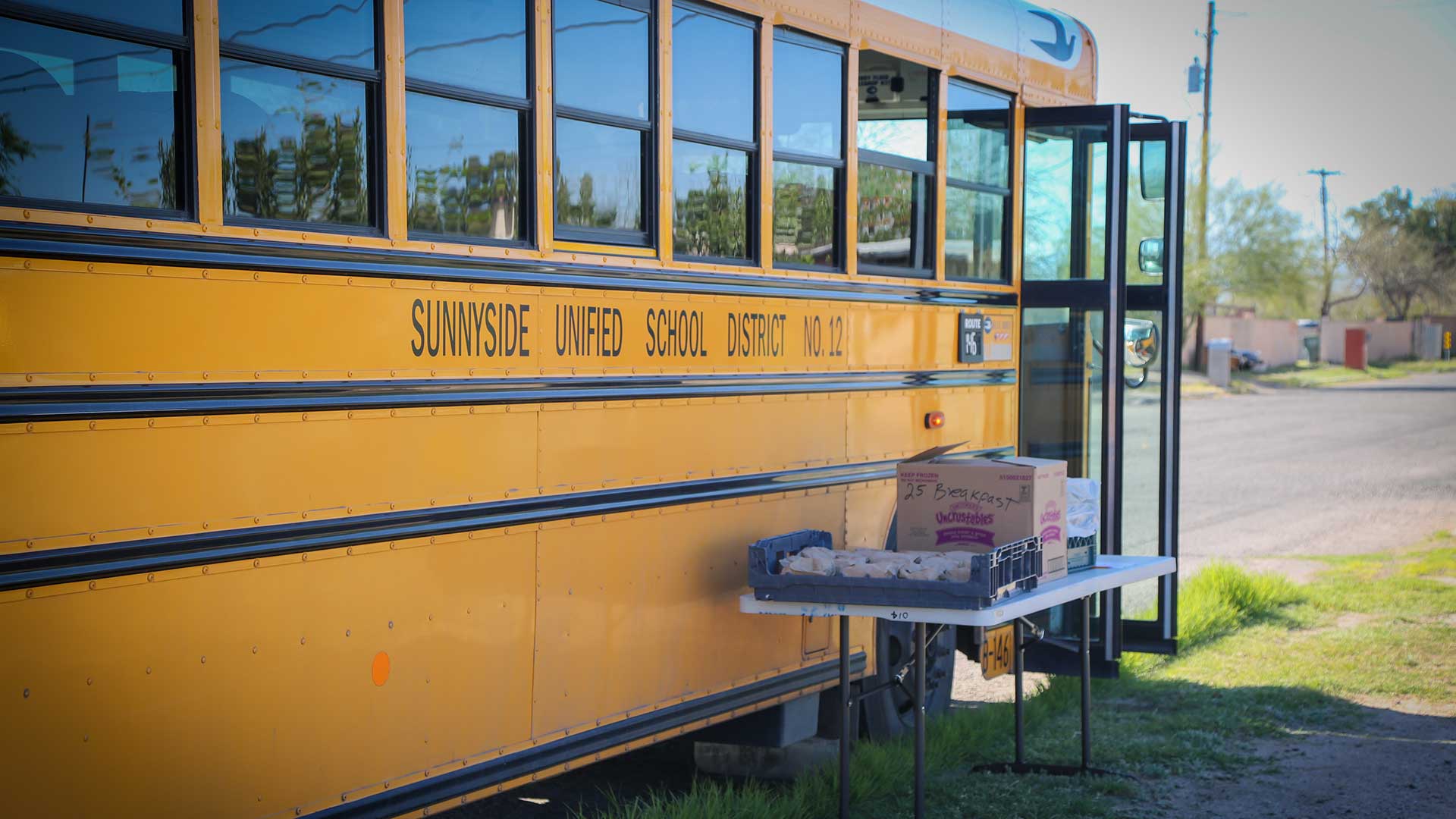

Sunnyside Unified School District is offering wireless hotspots and preparing meals to go for kids during the closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sunnyside Unified School District is offering wireless hotspots and preparing meals to go for kids during the closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Janet Olvera still has names on her list.

As the sole guidance counselor for the 600 students at Apollo Middle School in Tucson, she spends her days calling families to find out which ones have internet at home.

If they don’t, she’ll help them complete an application for Cox’s low-income internet service program, translating the instructions to Spanish if need be. Signing up for the service can be a challenge for those without internet; the only way to sign up is through the website.

She’s been able to get 25 students connected this way, but not everybody is interested. “Some never called back,” she said.

In Arizona, as many as 350,000 households — 13% of all households in the state — don’t have an internet subscription, according to the most recent estimates from the American Community Survey.

Though Gov. Doug Ducey is beginning to lift restrictions on businesses, schools will remain closed at least through the summer. Leaders in education say the pandemic has revealed a stark digital divide among Arizona students, putting the promise of a public education out of reach for some.

“We’ve long said that there are communities in this state that don’t even have electricity, much less the internet access they need to get done what they need to get done,” said Christine Thompson, president of education nonprofit Expect More Arizona and former executive director of the Arizona State Board of Education

Numerous studies have consistently shown that internet access correlates with income. In Tucson, the digital divide is pronounced on the city’s south and north sides, areas that are poorer and more diverse than the rest of the city.

Percent of households without an internet subscription

For low-income students stuck at home, that can mean missing out on classes conducted over video conferencing apps like Zoom or Google Hangouts. It also means fewer opportunities to download and upload homework.

According to data collected by the Sunnyside Unified School District, which contains Apollo Middle School, as many as 1,400 students are not consistently showing up to online class.

Every school in SUSD is Title I, meaning they receive federal funds due to high concentrations of students in poverty.

“These issues we’ve been having are not new. They’re just exacerbated right now and getting more attention,” said SUSD Title I Coordinator Andrea Foster.

Sunnyside has been in a better position to adapt to remote learning than other districts, Foster said. Thanks to $27 million from a bond passed in 2011, SUSD had already been providing laptops to all students in grades four through 12. For families with no internet access at home, SUSD has set up 30 mobile hotspots on buses that distribute meals around the district.

Things are different in neighboring Tucson Unified School District. A TUSD survey estimated it needs over 23,000 devices for its students to transition to remote learning, and has been engaged in an expensive campaign to close its digital divide.

Cox has partnered with TUSD and other school districts to get families connected through a low-cost option called Connect2Compete. It’s only available to families with students who are enrolled in low-income assistance programs.

But the program is only available in areas that Cox serves, and Foster said not all families are covered, particularly those living on the San Xavier Reservation. “They don’t have service out there. They don’t have the infrastructure,” she said.

In Arizona, rural areas lack internet at greater rates than the rest of the state, but nowhere more so than on Native American reservations.

Internet service providers have been reluctant to bring fiber optic cables and cell towers into Indian Country. The reasons are myriad: a lack of federal funding, regulatory loopholes and little financial incentive.

Nearly 20% of reservation residents have no internet access at home, according to a 2019 study from the American Indian Policy Institute at Arizona State University. A third rely on a cell phone for internet access.

But when it comes to finishing homework, working remotely or using common programs like spreadsheets and word processors, a cell phone can be woefully inadequate.

“What this pandemic has really shined a light on is not just that internet access question, but the question of devices,” Thompson said. “When you ask if someone has access to internet at their home, sure, but does one parent have a phone that everyone shares?”

ISPs won’t be able to provide discounted services indefinitely, and students who borrowed devices through their school will be expected to give them back.

Thompson said she hopes a more permanent solution to Arizona’s digital divide will come out of the pandemic.

“That’s going to be critical not just for educational needs but really for economic development in the future,” she said.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.