Listen:

By Andrew Bernier, Arizona Science Desk

FLAGSTAFF - A long-traveling space probe is approaching Pluto, and next month will bring marking humanity’s closest encounter with the dwarf planet.

The fly-by will provide important scientific data, and, perhaps, a boost and some fun for Flagstaff, where Pluto was discovered at the Lowell Observatory 85 years ago.

Pluto is the second largest object in the Kuiper Belt, a band of ice and metallic debris at the edge of our solar system. The space probe called New Horizons is scheduled to pass by in July after a nine-year journey, and Lowell Observatory’s Josh Bangle said he and the rest of the staff are ready to celebrate.

“Just to kind of theme the year, we decided that we’re going to call it the year of Pluto," Bangle said. "We’ve done some fun things around it to celebrate Pluto and its history to Flagstaff.”

Pluto dome telescope, Flagstaff, Arizona

Pluto dome telescope, Flagstaff, ArizonaPluto was reclassified from planet status in 2006 after improved observational technology showed it isn't the same as the other astral bodies orbiting the sun. It is a bit of a sensitive topic around town, but Bangle said some people hope the data sent back may show otherwise.

“I think there’s a lot of people who are like, 'Hey, maybe it will become a planet again and maybe there will be hundreds of more planets we’ll discover after this'," he said.

Although Pluto and the many objects that make up the Kuiper belt have little chance of achieving planet status, there may be a lot to learn about the solar system from what is on its surface.

Scientists already have an idea of Pluto’s surface from decades of light gathering in the form of wavelengths, called spectral data, from observations by land-based telescopes and the satellite-borne Hubble telescope.

Will Grundy, a New Horizon’s co-investigator, said science needs a closer look.

“The real difference that you get when you send a spacecraft somewhere is spatial resolution," Grundy said. "So instead of seeing the entire globe as one point, you can make out the different landscapes and distinguish what they are.”

The surface of Pluto reflects sunlight onto spectrometers, devices that record spectral data. Different substances with different physical and chemical properties will alter the frequency of the lights’ wavelengths, which are then absorbed and recorded into the spectrometers. These are matched with wavelengths of known substances such as methane, nitrogen and carbon monoxide.

“You need to know the properties to be able to understand how they act in the environment of a planet’s surface," Grundy said. "And understanding how they act gets you to the processes that are at work. The action of processes over time sculpts the land.”

Ultimately, studying the surface of Kuiper Belt objects may give a better insight to the origins of material in the solar system, including what’s on Earth. Grundy said a lab at neighboring Northern Arizona University is already recreating ice samples based on pre-existing data and soon will do the same with information from New Horizons. This can give researchers a better idea of what is happening on the surface.

“What you really want to get at is the origins," he said. "How did that get to be there in the first place? So, what we’re doing in the laboratory is a key piece of information that feeds into how we fully understand the processes in order to run the clock backwards to the starting point.”

Inside the lab is $1 million worth of equipment, and there are only three other labs like it in the world. Stephen Tegler, who oversees NAU’s Ice Lab, walked through the re-creation process.

“We cool it down to the temperatures that are representative of what’s on the surface of Pluto - hundreds of degrees colder than room temperature," Tegler said. "And these other things that are making a little bit of noise, they’re different kinds of pumps basically simulating the vacuum of space. So we’re simulating the surface of Pluto.”

Tegler and his team add various gases and liquid nitrogen to recreate the volatile ice and hit it with light to match the data sent from observatories and soon information from New Horizons.

“And by finding that match, that allows us to infer and get the most out of the data that comes back from the spacecraft mission," Tegler said. "What’s the temperature of the ice? What’s the phase of the ice? What’s the composition of the ice? And to get the most out of the spacecraft data, you really need a robust laboratory to investigate, to poke and prod the ice if you will.”

Once the lab is turned off, the ice melts instantly and the gases are released outside. But as more images and spectral data come in from New Horizons, that droning may become more constant as the surface of the once planet nearly three and half billion miles away becomes much clearer.

Arizona Science Desk is a collaboration of public broadcasting entities in the state, including Arizona Public Media.

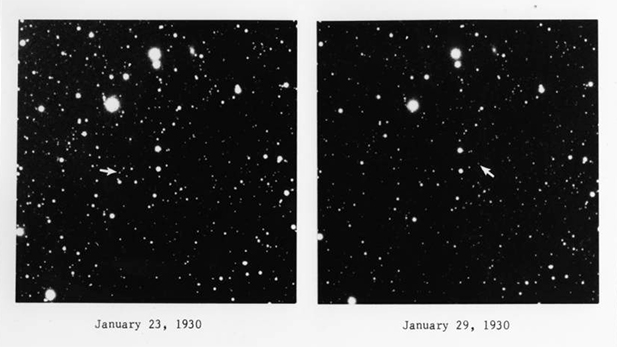

Copy of sections of the original glass plates on which Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto. The arrows show Pluto's movement against the background stars. Tombaugh discovered it by blinking the plates back and forth on a machine called a blink comparator.

Copy of sections of the original glass plates on which Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto. The arrows show Pluto's movement against the background stars. Tombaugh discovered it by blinking the plates back and forth on a machine called a blink comparator.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.