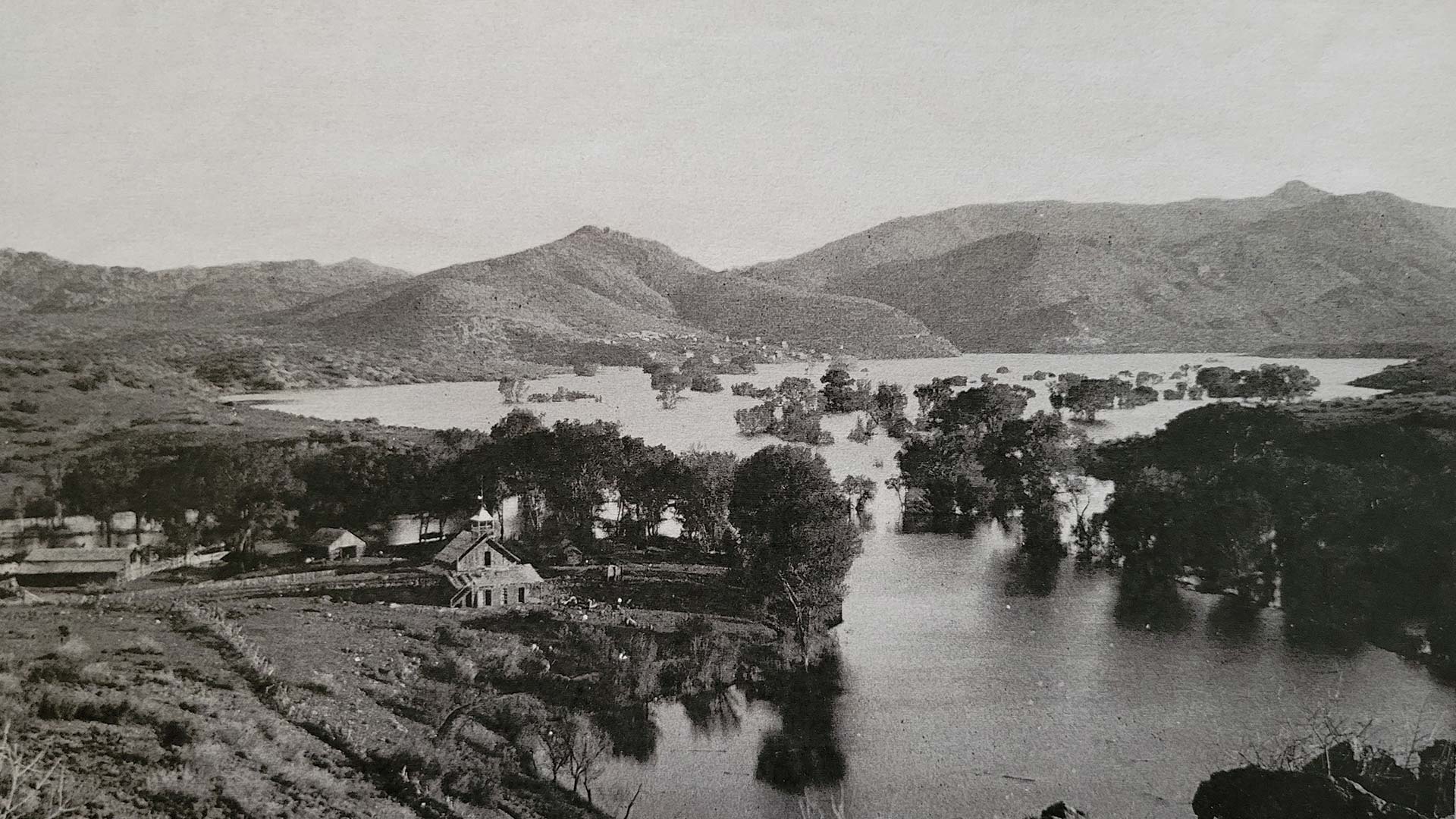

The Hassayampa River as it runs through Cooper Ranch.

The Hassayampa River as it runs through Cooper Ranch.

Tapped: Season 2, Ep. 1: When dams break

Tapped returns with a season that examines water infrastructure. On this episode, what happens when dams break?

Episode transcription

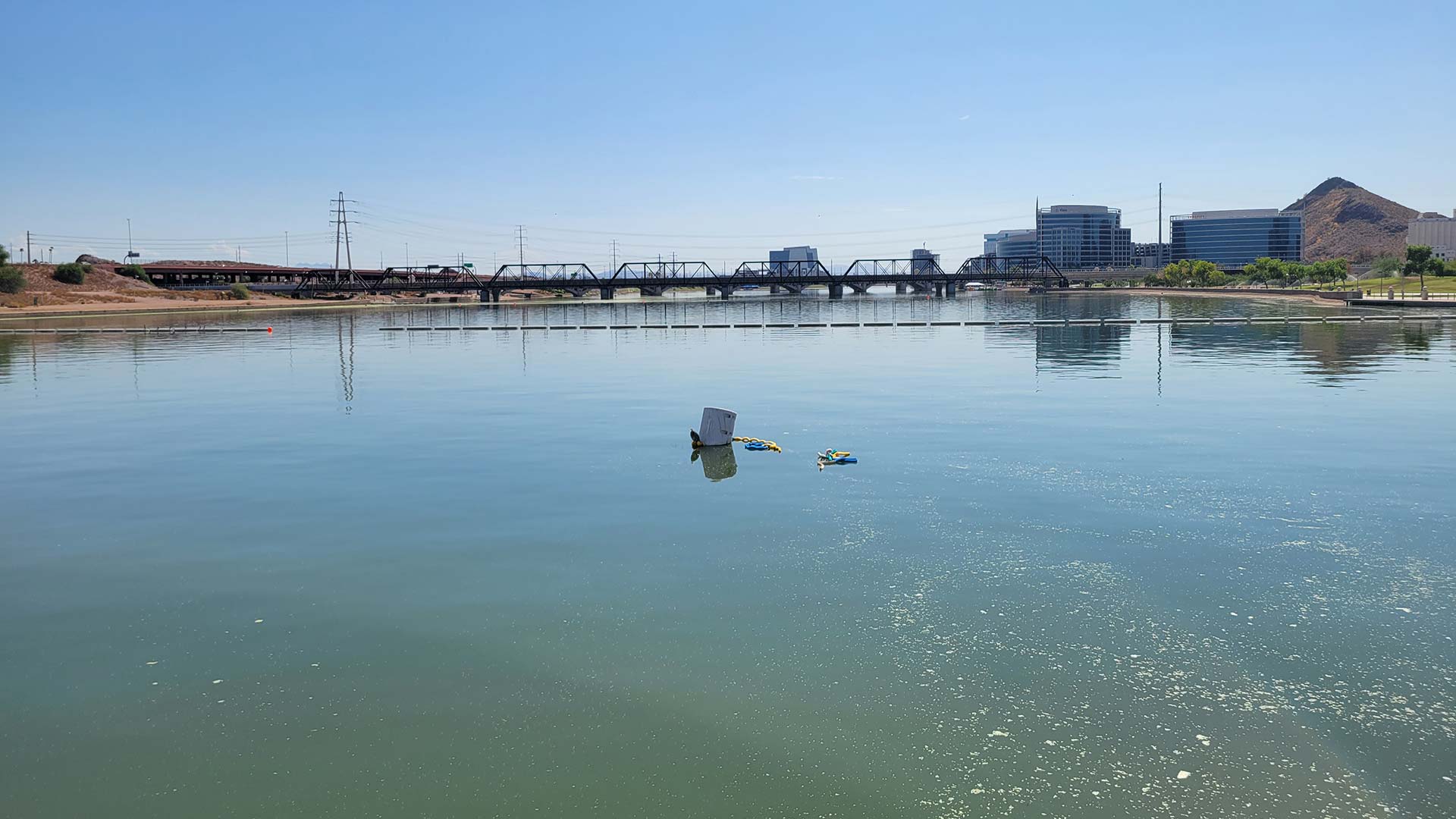

Zac Ziegler: I'm standing on the dam that holds back Tempe Town Lake. If I say dam failure in Arizona, this is probably the spot that you think of.

In July of 2010, the rubber bladders that held back this body of water began to fail, and within 24 hours, a billion gallons of water were turned loose on a normally-dry portion of the Salt River.

The costs of this dam failure weren't catastrophic. There were no casualties, no one's property was flooded. It cost the City of Tempe more than $50 million to fix it and, for a while, the lake was . . . like so many bodies of water in Arizona, drier than its name would indicate.

Today, without some prior knowledge, you can stand on the edge of the lake and not know that it ever happened.

(music fades in)

Water is a precious commodity in the southwest, and the things we build to improve access show just how precious it is. We've spent billions of dollars on dams, canals, wells, and much more, just so that, when we want water, it's there.

This is Tapped, a podcast about water. I'm Zac Ziegler. This season, we're looking at what we do to make water usable and the ramifications that can have.

In this episode, we look at dams. As America's infrastructure ages, how much do we need to worry about these massive structures? And what does it look like when one gives way?

VIEW LARGER Tempe Town Lake from a pedestrian bridge near the replacement dam.

VIEW LARGER Tempe Town Lake from a pedestrian bridge near the replacement dam. (music fades out)

(newscast audio)

Welcome back, continuing to follow breaking news tonight at Tempe Town Lake. A dam failure on the west side of the lake has thousands of gallons of water right now flowing into the Salt River bed.

ZZ: It's easy to see why the dam failure at Tempe Town Lake had a lot of people concerned and prompted media coverage, like the newscast you just heard from ABC 15 in Phoenix the day that the leaking was discovered.

The dam is classified as a significant hazard dam, meaning there was some chance for property damage, but the likelihood of people being endangered was low.

That's not to say there are no worries though.

Stewart Vaghti is the principal project manager for geotech dams and hydraulics at Gannet Fleming, the firm that built the replacement dam.

Vaghti: "Sometimes there's contractors and environmentalists that are in the river, whether it's for doing studies or there's utilities that cross the river. Sky Harbor is not that far downstream, so they sometimes have personnel that are in the river for maintenance. Or there's some utility crossings across the river so it's not that it's not without risk."

ZZ: Luckily, the release happened over the course of several hours, not instantly.

And, the chance that the dam could have problems was known. In fact, the manufacturer had recommended a few years earlier that the dams be replaced at around the ten-year mark, and that work was scheduled to begin the same month as the break occurred.

In fact, he says that the maker of the dam, Bridgestone, was ready to start the replacement process.

SV: "But the manufacturer was getting out of the rubber bladder business, so they had a five-year window to essentially replace those bladder systems as part of the lease."

ZZ: And that's when Gannett Fleming came in to build a more permanent dam.

SV: "The City of Tempe wanted something more robust, steel and concrete was part of that selection process and that's where the the steel gate system came in, which is somewhat model after they have a very similar system in Oklahoma."

ZZ: The dam was put to the test this past spring, when the reservoirs for hydroelectric dams run by the Salt River project reached capacity.

SV: "Those types of events are great because they do allow us to see how it operates under a loaded condition, and in this case, SRP released water from the upstream dams that resulted in approximately between 20,000 and 30,000 [cubic feet per second] at the dam was being experienced. And that flow ended up spilling over the gates, ended up lasting several months during that release."

ZZ: For anyone who passed by the Salt River during those months, they saw a river running deep with water for the first time in years.

But, what Stewart saw was success for something that doesn't happen much any more, a dam passing its first big test.

SV: "New dam construction is a little bit less frequent now than it was 50 years ago. The 60s and the 70s were the heyday of dam design and construction across the US. Being able to design and build a new dam today is relatively infrequent compared to what it used to be."

ZZ: He says this being a replacement dam means a lot of the variables were known, so it wasn't like they were taking on an all-new project. But it's still different from what most dam work is now, making sure an aging dam with issues doesn't have the same fate as the first Tempe Town Lake dam had.

SV: "Condition assessments, assessing risks of current dams, looking at repair remediation, essentially the ultimate goal is to keep the risk down and extend the service life of these old dams because the cost to build a new dam makes it very challenging, and so these are very important assets to our community."

ZZ: These days, that's where a lot of the work is. Just ask John Moyle, who is retired, but continues to be involved in the industry through the Association of State Dam Safety Officials and consulting on the east coast.

When we spoke, he was deep in such a project.

JM: "I had to do an emergency inspection down in Delaware today. I'm helping Delaware do some damn safety work. The chief engineer that's normally here, she's on vacation in Florida. So we had a small dam that had a sinkhole and it's going under the concrete spillway and starting to take material with it, which could ultimately lead to a failure of structure."

ZZ: That dam was in bad enough shape that Delaware started to drain the reservoir in order to relieve pressure.

JM: "So the water level when I was out there today, it already dropped almost a foot since yesterday when they removed some flashboards."

ZZ: A routine inspection caught the issue, and the dam was given a rating of unsatisfactory, one of two grades that means work is needed.

JM: "An unsatisfactory means that there's a problem with the dam today that could lead to failure.

ZZ: The other is poor . . .

JM: "Which means that there's some sort of deficiency whether it doesn't meet current engineering design criteria with respect to the state regulations or is just in total disrepair from the standpoint it hasn't been maintained."

ZZ: How often a dam is inspected usually has to do with the state it's in and how big of a risk it represents. There's also a grading system for that, remember when we heard that Tempe Town Lake was a significant hazard? That's the scale we're talking about now.

JM: "For high hazard dams, they're usually inspected on an annual basis by a licensed professional engineer, and it varies state by state. In certain states, and I believe Arizona is one of these cases, they actually send out an engineer from their office to do the inspection. When I worked in New Jersey, the inspections were required to be done by the owner's engineer and the report submitted to the state. . . Otherwise if it's a significant hazard, sometimes it's every three years, every five years, and then the low hazards are usually every five years or based upon an as needed basis if somebody sees a problem."

ZZ: Those two grades are among the criteria considered when another group that John is a member of, the American Society of Civil Engineers, issues its periodic report cards for each state.

In the last one, Arizona received a C.

JM: "You know, the C average is average, and when you look at where most dam safety programs, there are programs in some states that have one person responsible for hundreds of them. So to get out and be inspected, let alone get repaired in a timely manner, it's a serious problem throughout the United States."

ZZ: When I asked both John and Stewart about the fact that Arizona and the U-S in general really doesn't fare too well on the state of its dams, they both made similar statements.

JM: "Dams are forgotten infrastructure unless you have a problem and people are evacuated, where you have a major flood and you have dams fail."

SV: " And if it's not in the news and it's not grabbing attention, that tends to slow down. And so it often takes catastrophic events like the Oroville failure in California or the Flint water crisis to generate funding for infrastructure."

ZZ: The 2017 Oroville Dam crisis began when unusually heavy winter rains damaged a spillway on a dam that sits about 65 miles north of Sacramento.

Almost 190,000 were evacuated from an area known as the Feather River Basin for a couple of days until the dam's safety could be guaranteed.

A report found that the dam's spillways were insufficient. California's Department of Water Resources came under criticism for ignoring warning signs about the dams spillway design.

While Oroville is an example of a recent issue where a dam was in danger of collapsing, you can head back to Arizona's territorial days and find a terrifying example of what can happen if those issues aren't caught early on.

(audio of running river fades in)

It's a lovely summer day along the Hassayampa River west of the Bradshaw Mountains in a remote area of Yavapai County.

I'm not far from the site of a recent tragedy, the spot where the Granite Mountain Hotshots died battling the Yarnell Hill Fire a decade ago.

Mary Cooper's family has run livestock on this land for generations, dating back to a time when the site of her home would have been under a few feet of water because of the Walnut Grove Dam.

(audio of running river fades out)

These days, she has taken to commemorating the family history in sculptures.

Cooper: "My grandmother, this bronze over here has the story of how she met her husband, my grandfather, in Skull Valley. She came from Texas. Grandma came to visit her cousin Delia and aunt Sally, so they took her to the 4th of July Prescott rodeo. She bought a picture postcard and it had this cowboy, bronc rider. So she wrote on the back of it, 'I'm going to marry a cowboy just like this.'"

ZZ: She sent that postcard back to her family in Texas and decided to stay in Arizona. She needed someone to help fix the family windmill, and the owner of the Skull Valley General Store introduced her to Roy Cooper. The two were smitten with each other from the first moment.

MC: "So they were married and after they'd been married a little while, her sister met her husband and said, 'Well I'll be gosh darn, that's the cowboy on the picture postcard that you sent me!' What are the odds of that?"

ZZ: Her grandma and grandpa raised goats on that land. The family later switched to cattle. They sell their grass-fed beef at farmer's markets and online.

We've been sitting in her living room to this point, looking at old pictures of the dam and her sculptures. But now, we head outside and walk down a 20-foot embankment to the Hassayampa River Valley.

(audio of running river fades in)

Mary has been barefoot for my entire visit, and she and her dog Havoc get in the water the second we're near it.

Mary Cooper and her dog, Havoc, enjoying the Hassayampa River.

Mary Cooper and her dog, Havoc, enjoying the Hassayampa River.

I take off my shoes, roll up my pant legs And join them.

She says her family has to work to keep flash floods on the Hassayampa from reclaiming the most valuable of its acreage, a patch of fertile grassland that was, for a handful of years in the 1880s, underwater.

MC: "That field over there and then the 80 acres on this side that we so much covet and take care of, because once it washes it out, it's not coming back. . . it's just amazing how much fill in and silt dropped in that one year that it was in."

ZZ: The river is running about ankle-deep now, but the monsoon to the north means it could get notably deeper at any moment. She says we could take the mile-long hike to the site of the dam's ruins . . .

MC: "The only thing I can say is that if you want to go, I'll get my shoes and a hat. We have conexes, you know, cargo containers, with blankets and will take water and jerky with us, in case we have to spend the night. That's what I do. I take water. I take jerky and I put blankets and coats in the conexes over there."

ZZ: I've got an appointment back in Tucson the next morning, so we'll stay up here with a view of cottonwoods and ash trees. And in the distance, Seal Mountain, so named because, despite the fact that the state seal bares the likeness of a miner from Cochise County, the mountain behind him is said to be right in front of me.

(audio of running river fades out)

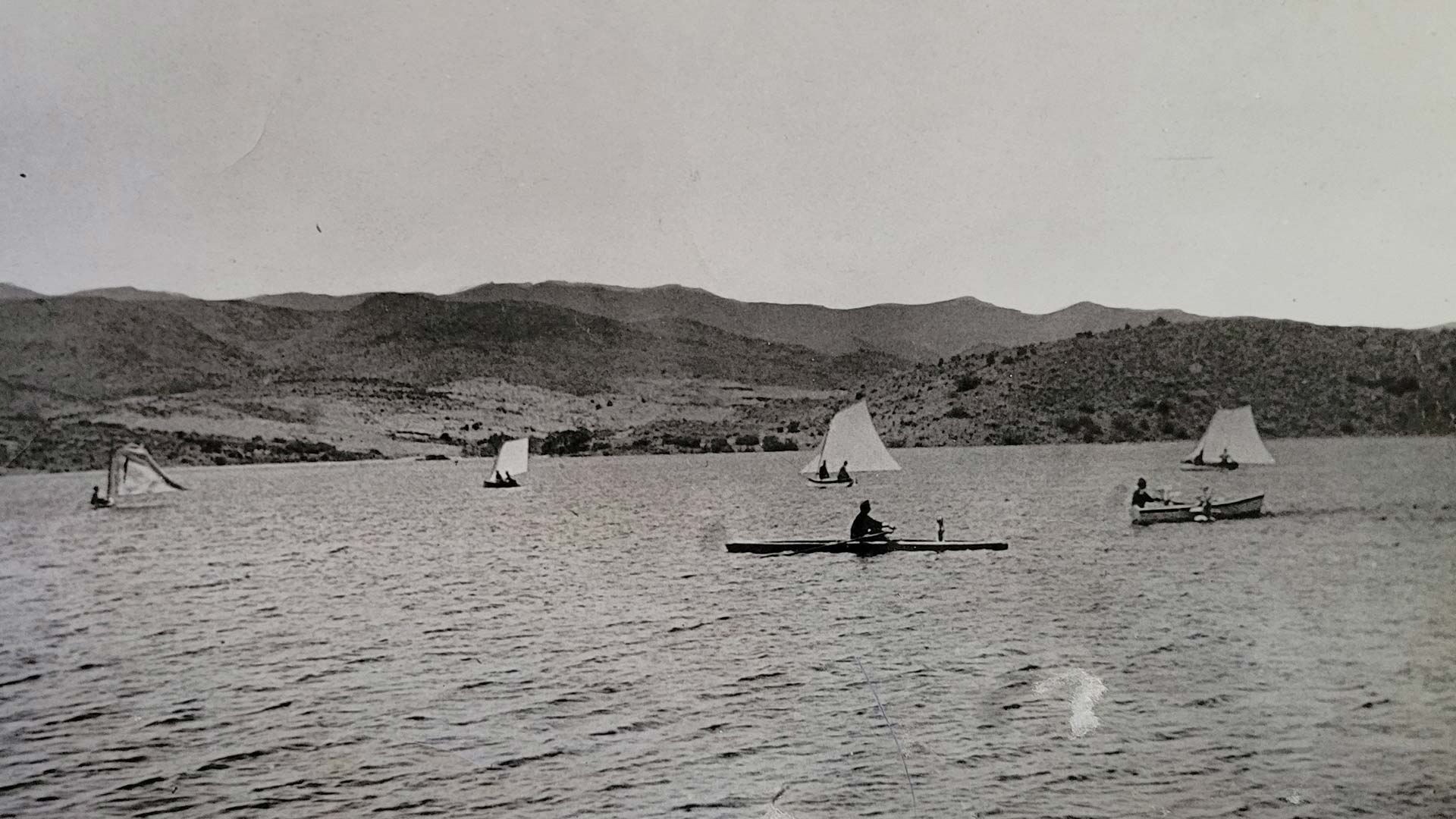

If you go back 133 years, you would have been able to take this view in from a sailboat floating along the four billion gallon reservoir made by the Walnut Grove Dam.

VIEW LARGER Sailboats on the short-lived Walnut Grove Lake.

VIEW LARGER Sailboats on the short-lived Walnut Grove Lake. To get the full story, you have to go back even further.

Prospectors discovered gold in the Hassayampa in the 1860s. In 1863, Henry Wickenburg, for whom the town of Wickenburg is named, established the Vulture Mine, which produced about 10 tons of gold and eight tons of silver in its lifetime.

And that caught national attention.

Jim Liggett: "It was a group from New York, and the real purpose of the dam was to do placer mining on the Hassayampa and on some of the creeks that run into the Hassayampa."

That's Jim Liggett, a former engineering professor at Cornell University and author of the book Arizona's Worst Disaster: The Hassayampa Story 1886-2009.

JL: "They had some stories about agriculture and so forth, but placer mining was the thing."

If you're wondering what placer mining is, let's start on the small scale. The most basic form is panning for gold.

(:12) "You know, the old fashioned guy on a burro goes and scrapes up some sand and shakes a pan and the gold settles. It's a hard way to make a living."

ZZ: You can increase the scale by using tools like a sluice box or a rocker. Think of the boxes with grates that people rock back and forth that you've probably seen in movies depicting old west prospecting.

Go up the scale more, add machines like trommels and dredges that move massive amounts of silt to places they weren't before. And that movement is the big environmental issue for the process.

It's said that parts of the San Francisco Bay have 20-foot wide sandbars caused by placer mining.

But, in pre-statehood Arizona, environmental ramifications weren't a thought. In fact, the biggest issue for building the Walnut Grove Dam was money.

JL: "The ironic thing about it is that the owners had trouble selling bonds in the east because everybody knew that Arizona was a desert and they were never going to have enough water to fill the reservoir."

ZZ: That caused the operation to run on a shoestring budget. Instead of hiring a civil engineer with a background in dam-building, they hired someone whose name may help with fundraising, William Blake

JL: "He was a mineralogist at the University of Arizona. He had no engineering experience, but he apparently was a well known fellow."

ZZ: That fame was probably because of his great-uncle, Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin.

Blake was fired shortly after construction began in 1886, but his design–and its flaws–stuck around.

JL: "They fired him and hired somebody equally incompetent. They built it down on a sand bed and never really got down to bedrock. And that pretty much meant that it was going to fail anyways, but the real cause of failure was an inadequate spillway."

ZZ: The spillway was big enough to handle the type of flood that happens every five years or so, WAY short of what is considered standard.

JL: "Dams are designed to withstand the maximum possible flood, sometimes it's a little less than that like a thousand-year flood."

ZZ: The spillway was also too short. If water went through it, it would end up in that sand bed. So a few floods would erode the already weak soil under the dam, digging a big hole for it to fall into.

The dam was close enough to finished in 1888 that they started filling. It over-topped for the first time in 1899. Then, it met its fate in February of 1890.

Mary Cooper's family lore describes the events leading up this way.

A photo labelled Walnut Grove Lake from the Cooper family collection. Mary Cooper said this photo is likely among those taken by William “Bucky” O’Neill, who was Yavapai County Sheriff from 1889-1890.

A photo labelled Walnut Grove Lake from the Cooper family collection. Mary Cooper said this photo is likely among those taken by William “Bucky” O’Neill, who was Yavapai County Sheriff from 1889-1890.

MC: "It was so stormy and they said it was really raining a lot and it was filling up fast, but they wanted to see it full. So they didn't open up the spill gates."

ZZ: Jim Liggett says that the issue could have been that the spillways were still under construction.

JL: "They were enlarging the spillway though, at the time of failure. But there was nothing they were going to do with that spillway that would have made it adequate."

ZZ: Mary remembers a visitor that her grandma wrote about. A man who, about 50 years ago, came with a death-bed confession from his great uncle.

MC: "This gentleman said the water was going over the dam successfully and would have been fine if his great uncle hadn't volunteered and said, 'I'm a dynamite expert. I can just put a little bit of dynamite on that spill gate and I can just blow it open and everything will be okay. And then what happened was he put too much dynamite in it and it blew the whole frame and then it started crumbling and his great uncle was just sick about it his whole life."

ZZ: Jim says he didn't see anything like that anywhere else in his research even if that story is true, it wouldn't have mattered.

JL: "There's three feet of water over the top of the dam, and for an earthen dam, this is fatal. This one perhaps handled it better than some because of the rock fill. It's still totally inadequate."

But, the failure didn't need to be as deadly, possibly not even deadly at all. Another mistake allowed that to happen. When the dam started to overflow, the project superintendent got worried.

JL: "And so he sent somebody downstream to warn people. They were, at the time, building another dam downstream, a diversion dam. And so there was a lot of workers. He sent somebody down to warn them, and he had to stop and fortify himself at the closest saloon, so he didn't make it."

ZZ: That man was Dan Burke, a local blacksmith with a known drinking problem. And Burke wasn't the only one who was sent. Another rider was sent later, when the failure was imminent.

JL: "He got close but he didn't outrun the flood waters. So most of the death occurred near the downstream dam, the diversion dam."

ZZ: Roughly 150 people died in the flood. Reporting about that aftermath is foggy, which is part of what caused what happened next, and also why Jim Liggett wrote his book.

JL: "You read so much that is just not true or contradictory. One article I read said the flood hit Wickenburg and destroyed everything, not a building standing. It didn't get very high in Wickenburg, as a matter of fact. It deposited a lot of sand and Henry Wickenburg's agricultural land was pretty much destroyed, I think. It was buried more than anything else, but also Wickenburg wasn't over knee deep."

ZZ: That reporting also said that Dan Burke was among the dead. But he was later found alive.

JL: "They wanted to arrest him for not doing his job. They had a hard time find a law that would apply to him. He got driven out of Prescott, I think, and he was later a farmer in Peeple's Valley."

ZZ: Then came the lawsuits. Jim found 13 in total. The biggest, two orphaned girls who sued for $50,000.

Henry Wickenburg was among the plaintiffs, unsurprisingly, seeking almost $8,000. Also not surprising, not all of the plaintiffs were on the up-and-up.

JL: "There was one family that got wiped out, reported that their two daughters were killed, as a matter of fact their two daughters were in Phoenix at the time." JL: "The company argued this was an act of God. They won the lawsuit in spite of the abundance of evidence of the poor design and the malfeasance of the owners."

ZZ: Ultimately, no one was convicted, no successful lawsuits. The company that was formed to build the dam and run the mines below went bankrupt.

JL: "It would be done so differently if it were done today. There would be a lot of data on what sort of floods to expect, and of course the other lesson is that the placer mining in that area would have absolutely destroyed a lot of the Hassayampa and tributaries to the Hassayampa."

ZZ: Mary Cooper says she's thought about what life would have been like had her family's ranch included lake-front property.

MC: "I guess it would have been totally different if the dam had been in, you know? . . . Then I'd be a boat kid, . . . because you know we had property real close, even if we never got to own this. So that would have been fun because I do like boats, and I've driven a Sea-Doo before and you know things like that and it was really a blast."

ZZ: Walnut Grove Dam was never rebuilt, placer mining for gold never became a thing in the area, beyond the occasional gold hunters, sifting through the sediment.

You can still spot them in the river valley on occasion to this day.

In terms of water quality, Liggett says it's probably good that the dam collapsed.

Placer mining can be a dirty process, and there would have been decades of it before the environmental consequences were fully known.

The Hassayampa historically fed into the Gila, but the river goes dry before that now, meaning that could have ended up in drinking water supplies.

Next time on Tapped, AZPM's environmental reporter, Katya Mendoza joins me to talk about those aquifers, more specifically, how we access the water in them through wells, and how we ensure that water is drinkable before it goes to users.

Tapped is a production of AZPM News.

This episode was produced and mixed by me, Zac Ziegler.

Our editor is Christopher Conover.

Our theme is by Michael Greenwald.

Visit our website in the podcast section of azpm.org for pictures, links and more.

Thanks for listening.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.