The Humboldt River between Lovelock and Winnemucca on February 25, 2020. The river provides water to towns along the I-80 corridor, mines, businesses and agricultural operations in northern Nevada.

The Humboldt River between Lovelock and Winnemucca on February 25, 2020. The river provides water to towns along the I-80 corridor, mines, businesses and agricultural operations in northern Nevada.

Twenty-two miles outside of the nearest town (Wells, pop. 1,246), graffiti on a crumbling hotel wall reads: “Home on the Strange.” Down a dirt road, there’s an abandoned car. An arch stands at the entrance of a dilapidated school. It’s what is left of a town that lost most of its water rights.

Around the turn of the last century, New York investors established Metropolis, Nevada as a farming community. By 1912, they had constructed a dam. They built a hotel, a school and an events center. The Southern Pacific Railroad constructed an office and built a line to the town.

Then the water ran dry.

Downstream irrigators in Lovelock, 250 miles away and with claims to water dating back to the 1800s, challenged the East Coast investors, and were successful in blocking the town’s water.

On a late February afternoon, near the remains of the former town, a plaque reads: “Lack of water, a typhoid epidemic, rabbits and Mormon crickets led to the town’s demise. With the closing of the post office and last school in the 1940s, the town ultimately died of thirst.”

What remains of a schoolhouse in Metropolis, Nev., a company town created by East Coast investors in the early 1900s. The town, in the Humboldt River basin, lost a portion of its water rights.

What remains of a schoolhouse in Metropolis, Nev., a company town created by East Coast investors in the early 1900s. The town, in the Humboldt River basin, lost a portion of its water rights.

Along the Humboldt River, a river so small Mark Twain once joked about jumping across it for sport, investors were there from the start. Water was often scarce, except for the flood years. Today a new type of investor has started eyeing water in the basin, less intent on building a new community than on supporting existing ones within one of the nation’s fastest growing states.

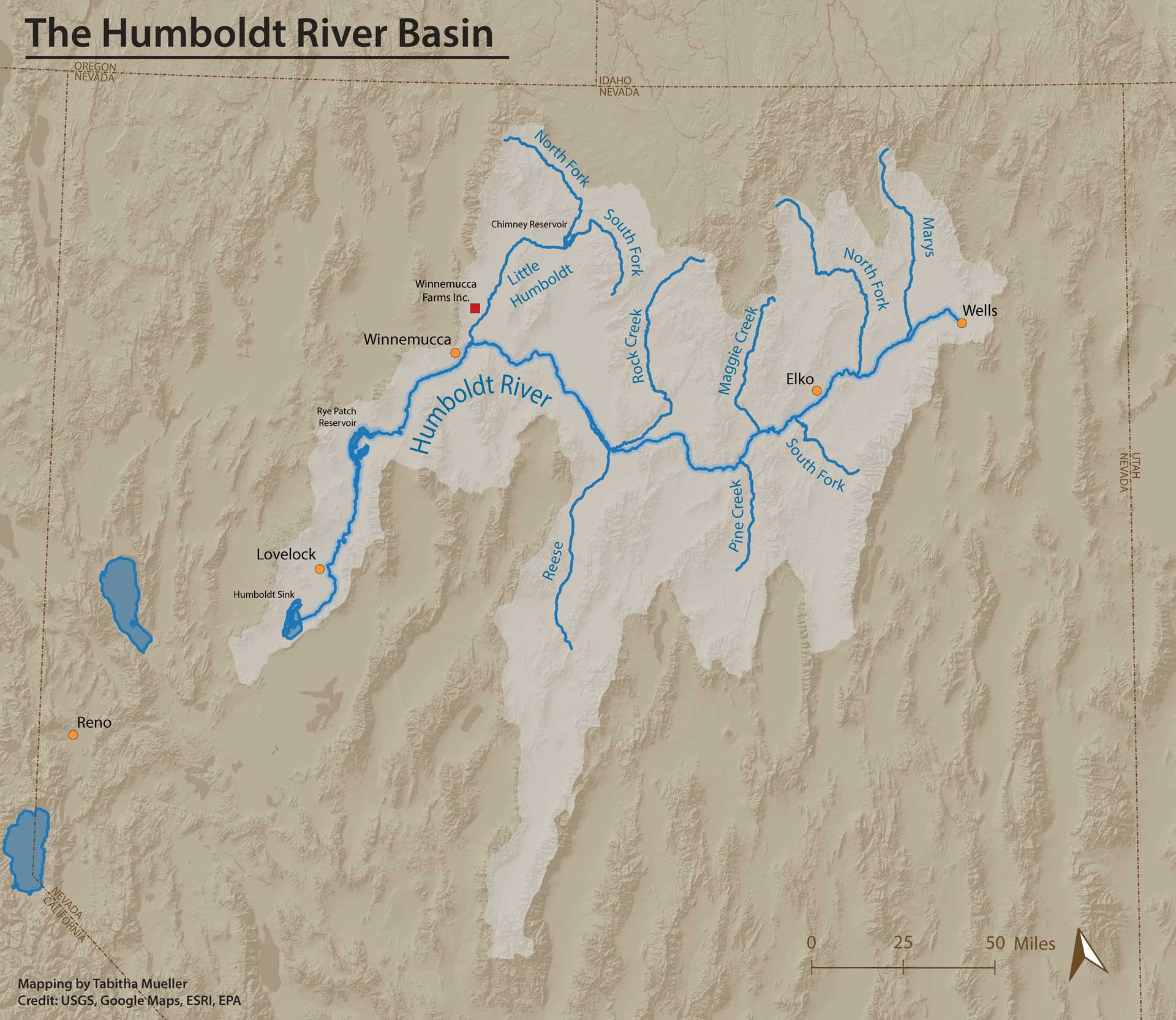

VIEW LARGER Map of the Humboldt River basin.

VIEW LARGER Map of the Humboldt River basin.

The “investment vehicle”

In 2009, U.S. Water and Land, LLC incorporated in the state of Delaware. The company would become an investment vehicle for Water Asset Management, a hedge fund based in New York that, over the past decade, has made strategic acquisitions of water rights across the West.

And U.S. Water and Land’s focus would become the Humboldt River basin.

It acquired Winnemucca Farms, a large-scale farming operation that has sold its potatoes to Frito-Lay. Importantly, the farm came with water rights, as many as 36,261 acre-feet of them. (An acre-foot describes the amount of water that can fill an acre of land to a depth of one foot).

In 2017, U.S. Water and Land applied for even more water. It asked state regulators to approve an application to capture up to 300,000 acre-feet of floodwater from the river, the same amount of water the entire Las Vegas metropolitan area is entitled to from the Colorado River each year.

The goal is to one day sell a portion of this water. For now, their focus is on the Humboldt River watershed, but in the past, the company has talked about water demands in fast-growing cities.

That worries rural counties, dependent on water for their local economies and livelihoods, and environmental activists, concerned about the ecological effects of exporting water elsewhere.

As a result, the project and others like it have been closely watched across the basin. People are not necessarily opposed to the concept of selling water. Yet they are concerned that these projects are a harbinger of things to come in an area where water is already a tense subject.

It’s a dynamic that plays out across Nevada. “Available water resources are primarily in the rural counties,” notes Jeff Fontaine, executive director of the Humboldt River Basin Water Authority.

Given that, “it’s pretty easy to think that’s where the growing urban areas are going to be looking for their water resources to meet the demand of their future growth,” Fontaine says.

Downtown Winnemucca, Nev., about 15 miles from Winnemucca Farms, on February, 23, 2020.

Downtown Winnemucca, Nev., about 15 miles from Winnemucca Farms, on February, 23, 2020.

More ways for water to run?

Water Asset Management is no stranger to those concerns.

In 2017, Disque Deane, chief investment officer for Water Asset Management, sat in frontof the Nevada Legislature with a simple warning: The state lacked the infrastructure to move water.

Unlike other Western states, Nevada has few ways to convey water long distances. California is plumbed with aqueducts. A canal bisects Arizona. Trans-mountain diversions move water from Colorado’s West Slope, where most of its rivers rise, to population centers on the Front Range.

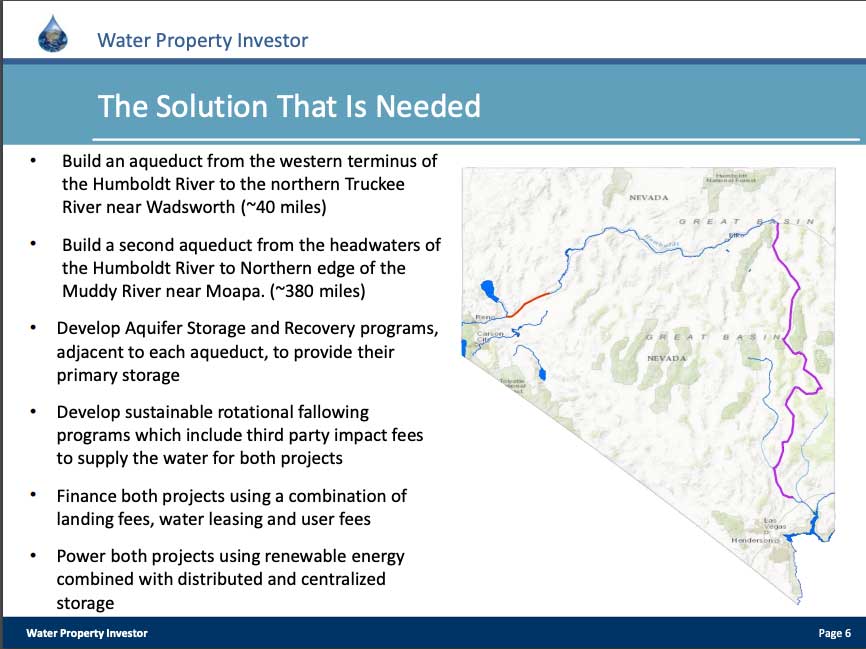

Deane said Nevada needed to consider two conveyances. One would connect the mouth of the Humboldt River with the Truckee River, which runs through Reno. The other would connect the headwaters of the Humboldt River with the Muddy River, a tributary of the Colorado River.

VIEW LARGER A slide from a Water Asset Management presentation to the Nevada Legislature lays out the fund's strategy.

VIEW LARGER A slide from a Water Asset Management presentation to the Nevada Legislature lays out the fund's strategy.

The idea comes with a big caveat.

“None of the things I’m talking about today work if the rural counties — and the farmers and the ranchers in those areas — are not in favor of these programs,” Deane told the legislators.

He stressed the need to set up rotational fallowing, whereby farmers are compensated to forgo irrigation in certain years, when water is needed elsewhere, without necessarily giving up their rights. When reached by email, Deane said he did not have anything to add to his testimony.

At the time, Deane also referred to another tool: aquifer storage and recovery.

This is the tool U.S. Water and Land proposed in its application to appropriate 300,000 acre-feet of floodwater off the Humboldt River. In years of high flows on the Humboldt River, the company would capture any flood water, pump it to Winnemucca Farms and store it in the underground aquifer. In dry years or times of scarcity, they could then market that water to those who need it.

The question is: Who needs it?

On its website, Water Asset Management suggests the water could be developed for a range of uses including for industry, for cities, for regional water use or even to supplement river flows. At one point, Winnemucca Farms applied to build a pumped hydropower project to store electricity.

Sam Routson, who manages U.S. Water and Land, said in response to emailed questions that “we are engaged in conversations with potential water users” both formally and informally.

He didn’t elaborate much more. The region’s largest purveyor, the Truckee Meadows Water Authority, which supplies the fast-growing area around Reno, says it is not currently interested. And the Southern Nevada Water Authority, which recently abandoned its own multi-decade effort to pump water from rural Nevada, has stated publicly that its focus is on conservation.

Routson wrote that the company is “focused on water scarcity and the importance of developing sustainable water management projects to serve the needs of the Humboldt River basin.”

When asked about a timeline for developing the asset, he wrote “the sooner, the better.”

“Expediting this and other sustainable water management projects will not only satisfy the water demands of Nevada's farming and ranching communities and growing population, but it should also strengthen Nevada’s negotiating position on Colorado River issues,” Routson said.

Regardless of where it’s used, the idea worries environmentalists.

In many of the uses that Water Asset Management proposes, water could be diverted from a river that needs every drop. That concerns longtime environmental activist Susan Lynn.

She says "there'd be an enormous impact on the people who live in central Nevada.”

As it is, Lynn notes that little water makes it to the end of the Humboldt River, which empties into a closed basin, or “sink,” with wetlands that can support migratory birds, waterfowl and fish.

The Humboldt River underneath Rye Patch Dam on Feb. 28, 2020 before irrigation season. This water will go to Lovelock, Nev. and empty into a closed basin that supports ecologically-important wetlands.

The Humboldt River underneath Rye Patch Dam on Feb. 28, 2020 before irrigation season. This water will go to Lovelock, Nev. and empty into a closed basin that supports ecologically-important wetlands.

Drought has already diminished the sink, with a wetland-dependent ecosystem used by Native American tribes since 2,000 B.C. The world’s oldest duck decoys were found in caves there.

“There’s no water in the sink except in really exceptional years,” Lynn said.

And it’s those exceptional years that U.S. Water and Land are targeting.

Less water, more demand

On the Humboldt River, downstream irrigators in Lovelock generally call the shots.

Lovelock farmers were some of the first to develop water on the river. Under the law, that gives them a priority to divert water in times of scarcity. Recently, it hasn’t always worked that way.

Between 2013 and 2015, Lovelock farmers saw little to no water.

In large part, that has to do with the geography of the Humboldt basin. Despite holding priority “senior” rights to water, the town of Lovelock in Pershing County sits on the final stretches of the river. When upstream groundwater users (with lower priority “junior” rights) pump water, it can diminish the amount of water flowing through the river, only intensifying the effects of drought.

And it leaves less water for the Pershing County Water Conservation District, despite its rights. Bennie Hodges, who recently stepped down as the district’s general manager, put it this way.

“All surface water users in the Humboldt River system, some years they may have a 20 percent allotment, some years 50 percent, some years 70 percent of an allotment,” Hodges explained in March. “And that’s all they get for whatever reason — drought, bad runoff, whatever.”

“But,” he added, “the underground [water users], they get a 100 percent allotment every year, no matter how dry it is. Yet they have a junior water right to all surface water rights in the Humboldt River drainage. That’s what gets to everybody. I don’t know how to put it any simpler.”

Downtown Lovelock, Nev., about 80 miles away from Winnemucca Farms, on February, 23, 2020.

Downtown Lovelock, Nev., about 80 miles away from Winnemucca Farms, on February, 23, 2020.

In 2015, the district sued to force state regulators to stop overpumping. That litigation is tied up in court. Several parties, including the city of Elko, U.S. Water and Land, and mining companies, have sought to intervene, worried further court action could harm their groundwater supplies.

At the same time, the state has contemplated regulations to manage groundwater and surface water together. Regulators said they are waiting on the results of a watershed modeling project.

Previously drafted regulations have looked at a program where groundwater users compensate downstream irrigators for lost water or pay to replace their water with a source elsewhere in the basin. Around the time those draft regulations were being discussed, U.S. Water and Land filed an application with the state to store as much as 300,000 acre-feet of floodwater in an aquifer.

Despite all the talk of drought, there are years when the river floods. And U.S. Water and Land believes if it can capture that floodwater and store it, people would want to pay for it one day.

“Directed and stored water will improve local and regional water supply reliability by capturing designated amounts of flood and other water that now flow unchecked and unused into the Humboldt sink,” U.S. Water and Land wrote in its 2017 application to state water regulators.

After all, many irrigators say they do not want compensation.

“They want their water.” Hodges said.

State regulators have not made a decision on U.S. Water and Land’s application. And Routson said it was still “too early to tell” if the eventual regulations would enable a groundwater market.

Yet the proposal to appropriate and store such a substantial amount of water prompted protests from four rural counties, state wildlife managers, water users, including the conservation district.

“This application could have profound consequences to existing natural resources and future water management within the county as well as its customers, culture and economy,” wrote Dave Mendiola, the Humboldt County manager, in a protest letter submitted in January 2018.

“While the county isn’t opposed to the concept of aquifer storage and recharge, Application 87492 in its current form raises more questions than it answers,” Mendiola wrote in the letter.

Irrigation at Winnemucca Farms on Feb. 23, 2020. The farm grows potatoes.

Irrigation at Winnemucca Farms on Feb. 23, 2020. The farm grows potatoes.

Not the first rodeo

Weeks before the irrigation season starts, the town of Winnemucca is quiet.

The Humboldt County seat has a population of about 7,500, making it one of the larger towns in rural Nevada. Even though it is about 500 miles north of Las Vegas and 160 miles east of Reno, there are always concerns in rural Nevada anytime someone talks about moving water.

Mendiola’s office is on the second floor of the Humboldt County courthouse, built in 1921. The courthouse has a marble staircase and ionic columns lining the second-story walkway.

Despite the official protest, Mendiola said the county was not necessarily opposed to the idea of storing floodwater. Protests on a water rights application do not always express total opposition, but allow parties to intervene. What concerned him was having one private company in control.

At the end of the day, he noted that the water “still belongs to the citizens.”

Instead, he suggested that it would be a project best completed as a collaboration between local governments and private businesses. The stored water could then be administered by a board.

“All the counties and municipalities that depend on the water would have a say in it,” he said.

One of the greatest challenges facing U.S. Water and Land is the cost.

The cost of such a project would be immense. In its water rights application, U.S. Water and Land predicted that the project could take about $100 million and take five to 10 years to build.

And the Humboldt River might only flood once or twice every 10 years, if at all.

“In theory, it might be a good thing,” Hodges said. “The economic feasibility of doing that, we question it because the occurrence of being able to [capture water] isn’t going to be very often.”

But any project to convey water away from its natural source strikes at larger concerns. And this is not the first time a business has targeted water in and around the Humboldt River basin. In 1995, state regulators rejected applications from Eco-Vision, a partnership looking to pump and move about 387,300 acre-feet of groundwater from the Humboldt River basin for municipal use.

Similar attempts have been made elsewhere in Pershing and Humboldt Counties, in areas near the Black Rock Desert, home to Burning Man. In 2007, state water regulators rejected a plan, submitted by a project known as Aqua Trac, to claim and pump groundwater to basins around Reno. Again in 2014, state officials received a proposal to ship Humboldt County water from areas within the Black Rock National Conservation Area to the Reno-area for industrial use.

Rye Patch Reservoir near Lovelock, Nev. on Feb. 28, 2020. The reservoir stores Humboldt River water for agriculture. But in many years, it isn't enough, and there is often a shortage of water on the river.

Rye Patch Reservoir near Lovelock, Nev. on Feb. 28, 2020. The reservoir stores Humboldt River water for agriculture. But in many years, it isn't enough, and there is often a shortage of water on the river.

Although the state allows for water to be transferred across groundwater basins, at least one county is working to place its own policy structure on regulating how water can be transferred.

Humboldt County, Mendiola said, is considering an ordinance with rules for transferring water outside of the county. The ordinance would outline procedures for getting a use permit.

“If you’re going to take a significant amount of water out of our county, we need to make sure that we’re going to be kept whole in some way,” Mendiola said in late February.

The cities might not want the water now. And Water Asset Management emphasizes that any water project would need buy-in from rural communities. It would have to be a win-win.

“Nevada’s urban and rural communities must work together to build, operate and maintain a sustainable water supply which will eliminate drought’s unique ability to prevent Nevada from reaching its maximum economic potential,” Deane told the Legislature in 2017.

But some neighbors of Winnemucca Farms remain skeptical: Everything comes at a cost.

“When you dry these counties up and quit farming, a lot of things happen. And generally, the world goes to hell,” says Tony Lesperance, a former director of the Nevada Department of Agriculture.

Lesperance owns property in Paradise Valley near Winnemucca Farms. He is wary of a private hedge fund developing water, and he worries that growth will come at the cost of rural counties.

“Right now, we've got plenty of water in Humboldt County,” Lesperance says.

“We've got a lot of irrigated land,” he notes. “The pivots are working. Alfalfa's starting to green up, everything's good. No problem. Could we lose that water? You better believe we could.”

This story is part of a series on water investment in the West, produced by KUNC in Colorado, Aspen Journalism, KJZZ in Arizona and the Nevada Independent.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.