Dr. Jasleen Chhatwal is medical director of Sierra Tucson and past president of the Arizona

Psychiatric Society.

Dr. Jasleen Chhatwal is medical director of Sierra Tucson and past president of the Arizona

Psychiatric Society.November 19, 2020

Featured on the November 19th, 2020 edition of ARIZONA SPOTLIGHT with host Mark McLemore:

-

The 2020 presidential election was one of the most stressful in American history. Voters across the political spectrum reported feeling that democracy, prosperity, and their physical & mental health were all on the line. Hear a conversation with doctor of psychiatry Jasleen Chhatwal about how to move past post-election stress. (See article below.)

-

Can we find better solutions to our urgent economic problems by building a culture of respectful listening, passionate advocacy and intelligent debate? Find out what a program called Voices On The Economy "VOTE" is doing to transform partisan hostility.

Amy Cramer incubated the VOTE Program at Pima Community College, where she is an economics educator. The program is taught in middle schools, high schools and institutions of higher learning around the country and around the world.

Amy Cramer incubated the VOTE Program at Pima Community College, where she is an economics educator. The program is taught in middle schools, high schools and institutions of higher learning around the country and around the world.

- Is it time for everyone to exhale? In a new essay, author & activist Adiba Nelson the emotional toll the last four years has brought to her life, and whether her faith in democracy has been restored.

VIEW LARGER Adiba Nelson with her daughter Emory.

VIEW LARGER Adiba Nelson with her daughter Emory. - And, award-winning author Fenton Johnson tells what he experienced as a volunteer poll watcher in Pima County during the 2020 election, and how he thinks he was changed by the experience. You can find a conversation between Mark McLemore and Fenton Johnson about his most recent book, At the Center of All Beauty: Solitude and the Creative Life here.

Fenton Johnson and his book 'At the Center of All Beauty: Solitude and the Creative Life'

Fenton Johnson and his book 'At the Center of All Beauty: Solitude and the Creative Life'

ARIZONA SPOTLIGHT airs every Thursday at 8:30 am and 6:00 pm and every Saturday at 3:00 pm on NPR 89.1 FM / 1550 AM.

This year’s election was fraught with anxiety for people on both sides. Dr. Jasleen Chhatwal

likens it to trauma.

This year’s election was fraught with anxiety for people on both sides. Dr. Jasleen Chhatwal

likens it to trauma.

Post-Election Partisan Hostility

One psychiatrist recommends becoming curious to overcome fear of the “other.”

By Laura Markowitz with Heewon Park

For many Americans—including people here in Southern Arizona—the red-blue rift doesn’t just feel like a heated debate about tax policies or health care or immigration. It feels like a war.

The 2020 presidential election will go down in history as one of the most emotionally stressful. In the midst of a pandemic, voters of all political stripes reported feeling as if democracy, prosperity, even their mental health was on the line.

Surveys of Trump supporters in blue states and Biden supporters in red states revealed that both sides were afraid to put up yard signs or drive around with political bumper stickers. They worried about vandalism and angry confrontations with people who supported the other candidate.

“When we live in an environment where we don’t trust others around us, that is a very traumatic experience,” says psychiatrist Jasleen Chhatwal. She is the chief medical officer at Sierra Tucson, a residential treatment center north of Tucson. She is also president of the Arizona Psychiatric Society.

Before the election, she helped people manage their election stress. Weeks later, many people still feel unsafe.

“Being hypervigilant, watching your back, trying to assess what you can or cannot safely say in a group—those are all components of trauma. And so in some ways the culture that we’re living in, with this extreme bipartisanship, is very traumatic for each of us because we are looking at other people as “the other.”

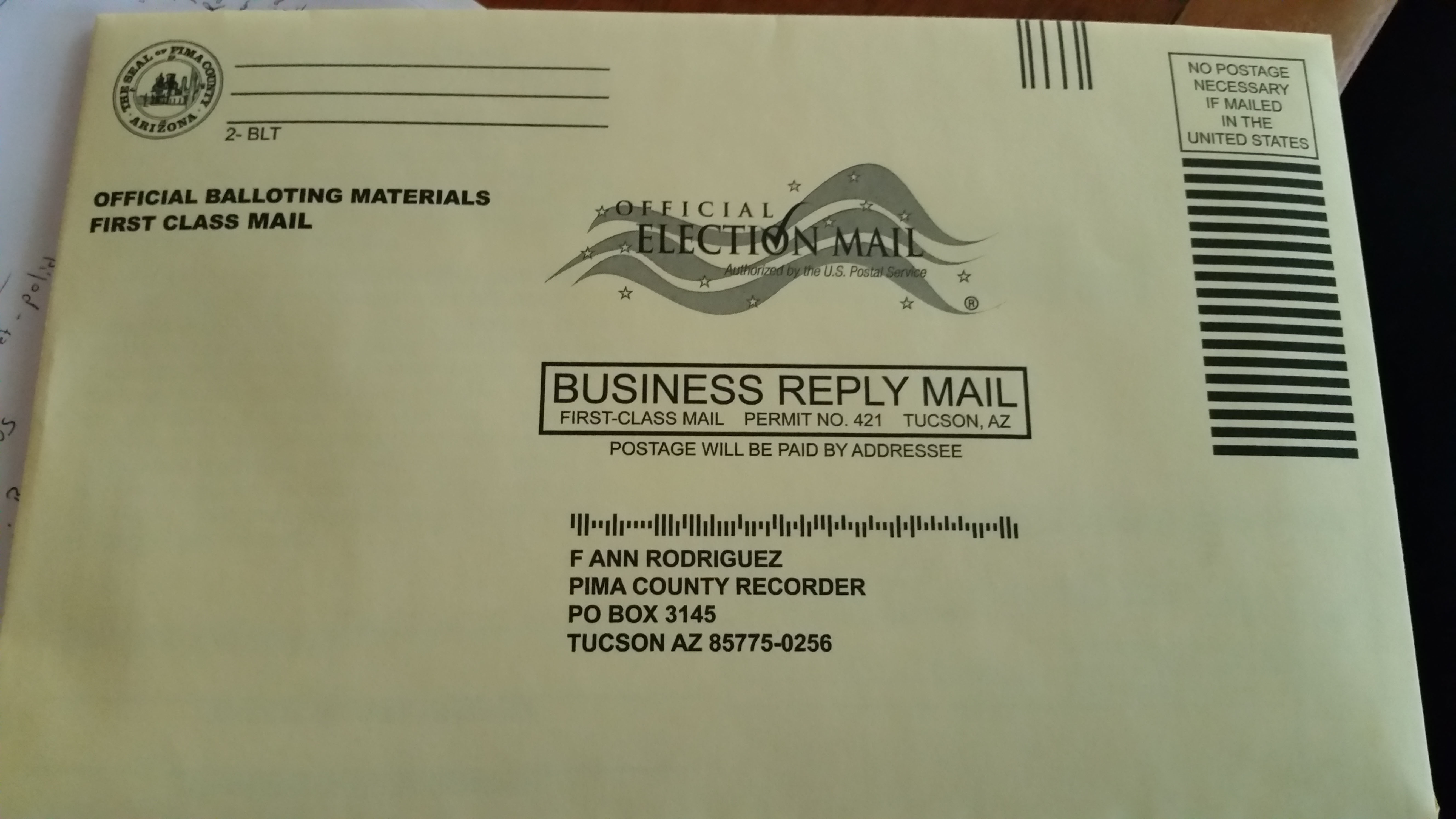

VIEW LARGER During the 2020 election, surveys showed that “red” voters and “blue” voters alike felt nervous

about putting up yard signs and bumper stickers for their candidates.

VIEW LARGER During the 2020 election, surveys showed that “red” voters and “blue” voters alike felt nervous

about putting up yard signs and bumper stickers for their candidates.

Neuroscientists say we’re hard-wired to fear the other. In other words, we can be xenophobic. It leads us to feel less empathy for those who are outside our group.

“Biologically, evolutionarily, we have always been taught we need to stick with our tribe,” says Chhatwal, “because people who are different—who are not our tribe—will come attack us, they’ll take our food, they’ll kill our children, they’ll take our land."

So we’re sitting at home wondering about our neighbors. Are they on our side? Can they be trusted? Should we be afraid?

“That’s how we survived out in the wild for a long, long time,” she says. “Even though you can’t see partisanship on the outside, we do have assumptions about people who live in a certain part of the country, belong to a certain party, and people who look a certain way. That starts to then further feed into that trauma of living in a place where you have to constantly watch your back, be hypervigilant, figure out who’s my friend and who’s my foe.”

She says we end up confining our interactions to people who share a common belief system.

That might not sound like a problem because, after all, we have more in common with people who think the way we do. But when we limit our contact with those who think differently than we do, we have fewer opportunities to make meaningful connections. And then it might be tempting to start thinking, “Hmm. If only those ‘others’ would move to another country then our problems would be solved.”

Entertaining thoughts about erasing the “other” only aggravates our stress. Chhatwal says there’s a better method for making ourselves feel less afraid, and that is to look for the humanity in others.

She works at Sierra Tucson, with coworkers who belong to both parties. And she says they all genuinely like each other.

“And I know very clearly from being Facebook friends with people that there are people on both sides of the aisle,” says Chhatwal, “and they’re all wonderful people. Sometimes it does make you question when you know somebody like that: 'Oh, well, what am I missing?' Right? And sometimes I’ve even thought to myself, ‘Wow, if they thought so differently from me how come they still like me? How come I still like them?’ ”

VIEW LARGER After the election, many people still suffer from the mental, physical, and social impact of

partisan hostility, according to psychiatrist Jasleen Chhatwal.

VIEW LARGER After the election, many people still suffer from the mental, physical, and social impact of

partisan hostility, according to psychiatrist Jasleen Chhatwal. “Sometimes I think curiosity is what can really save us. To be curious about why this person feels differently than I do. And in some ways, people being from different parties is like being from different cultures. And so as we have discussion about race, we have discussions about immigration, we have discussions about bipartisanship, the best thing we can really do is to be curious, because we can drive our own assumptions. We can think, ‘This person must believe this. That is why they chose so-and-so candidate.’ But we don’t really know. We haven’t lived their life. We haven’t had their experiences.”

Jasleen Chhatwal says if we can no longer love our neighbor as we love ourselves, and if we can no longer see somebody else’s point of view, then we cut ourselves off from a part of our own humanity.

“Becoming less human is really never the path to greater happiness or greater satisfaction in life,” she says. “Let’s just be human. Let’s be curious about each other’s experience. Let’s use this as an opportunity to maybe get to know each other a little bit better.”

Produced by Laura Markowitz with production assistance from Heewon Park.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.