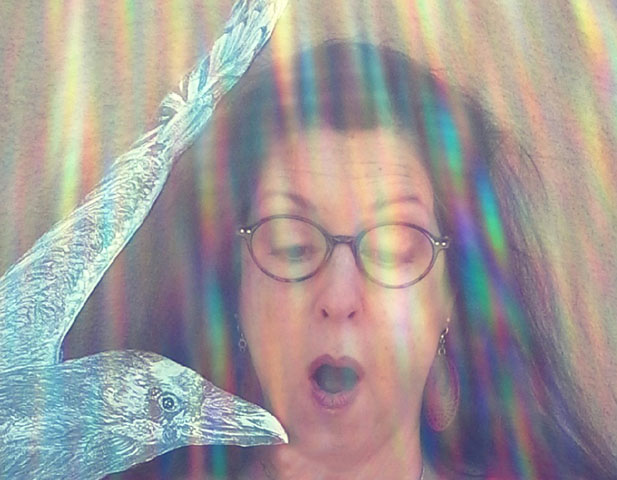

Gila woodpecker claims a cactus fruit -- original wildlife illustration.

Gila woodpecker claims a cactus fruit -- original wildlife illustration.

Paying Attention: Gila Woodpecker

© Beth Surdut, 2018

Welcome to my 24-hour, all you can drink, outdoor bar. In other parts of the country, I served hummingbirds a combination of boiled water and sugar from these red feeders, but when I moved to Tucson, I had some surprise patrons belly up to the bar.

Gila woodpeckers — Latin name, Melanerpes uropygialis — are quite dapper, with black-and-white checkered and barred wings and tail, creamy café-au-lait head and body, with a golden tinge on the belly, and distinctive white wing patches that show when they fly. The males sport what looks like a red lipstick streak on their heads. Their voices, clearly heard, even when competing with traffic noise, sound like squeak toys having a party.

Giddy talkers, they announce their arrival at my hummingbird feeders, which they drain almost daily, even after visiting the agave flowers.

The woodpeckers show up multiple times a day, announcing their arrival as they land, yakking as they jump down the bark to the feeder, still vocalizing when they land, and in-between drinks, calling back and forth from neighboring utility poles.

VIEW LARGER Gila woodpecker father feeds chick in a mesquite tree.

VIEW LARGER Gila woodpecker father feeds chick in a mesquite tree. You should hear them amp up the sound when the feeder is empty! In summer and early fall, when the Lesser long-nosed bats drink from those same feeders every night until there is not a drop, the woodpeckers serve as my morning wake-up call.

Yet, unlike the resident Anna’s hummingbirds that share the feeder, hover around me, poke me, sometimes even follow me into the house when I carry the feeder in for a refill, the Gilas are always wary. Seeing me through the window, as I rise to attend to them, sends them fleeing, but they quickly return.

To me, woodpeckers are marvels of anatomical engineering.

Gila woodpeckers weigh about 3.5 ounces—the same as a deck of cards—and are 8-10 inches long. They have two toes pointing forward and two pointing backward that help them move on vertical surfaces, and very stiff tail feathers that they can press into even prickly cactus spines to help stabilize while whacking away.

Their sturdy beaks come to a gradual point, and are self-sharpening. They have as much chance of fitting into those hummingbird feeder holes as a camel does through the eye of a needle. When I first watched the woodpeckers stand on the feeder, tipping it with their weight as they pressed the end of the beak to the hole, I thought they were sloshing the liquid, so they could get a taste. I was wrong.

VIEW LARGER A Gila woodpecker samples octopus agave blossoms.

VIEW LARGER A Gila woodpecker samples octopus agave blossoms. What they do have in common with hummingbirds, are tongues so long that they wrap around their skulls. A woodpecker’s tongue is sticky and barbed at the end. It is guided by the flexible, muscle-covered hyoid bone that is attached at the right nostril, dividing into two parts between the eyes, wrapping all the way up and around the back of the skull. There, the separate pieces rejoin and attach to the muscle of the tongue. When the muscles surrounding the relaxed hyoid bone contract, they propel the tongue forward and out of the beak.

These birds bang on surfaces at an average of 12,000 times a day,15 miles per hour. The hyoid bone acts as a seatbelt for the bird’s brain, stabilizing the head and spine, protecting it from neurological trauma.

Woodpeckers’ brains are also tightly seated in their skulls—much more so than human brains, which can slosh on impact.

The upper beak is longer, so it absorbs more of the shock than the lower beak. The force travels up the beak, meeting the hyoid bone in the nostril, before hitting spongy bone in the skull. The stress then travels along the path of the hyoid bone, diffusing into the muscles that cover it.

VIEW LARGER An omnivorous Gila woodpecker feeds its young a piece of a packrat.

VIEW LARGER An omnivorous Gila woodpecker feeds its young a piece of a packrat. Woodpeckers, who are omnivorous, glean insects from the surface of the bark. Their hearing is so astute, they can detect insect activity well below that, which may explain the added popularity of the rotting mesquite tree where a feeder hangs. The tap-tap-tapping isn’t all about food. On noisily resonant surfaces, such as metal screens and antennas, the birds are announcing their presence and territory.

Gila woodpeckers mate for life—unlike polygamous Acorn woodpeckers. During spring and summer, they are capable of producing two clutches of eggs—three to five each time-- and gestation period is only two weeks.

Both parents take part in nest building and feeding, usually in a mesquite tree or a saguaro cactus, which comes with the bonus of sweet fruit in summer.

VIEW LARGER A male Gila woodpecker peeks out of its nest in a Saguaro cactus.

VIEW LARGER A male Gila woodpecker peeks out of its nest in a Saguaro cactus. The birds perform a kind of surgery when they drill into a cactus to create a nesting site. The plant heals by covering the wound with sap that slowly hardens, forming a solid casing, called a boot. Drying time can take a few months, so holes are excavated, but not used until the next brood. And other birds, lizards, snakes, or rodents may move into these time-share condos.

Gila woodpecker families are around my house daily, so when I saw a fledgling with its head turned and tucked under fluffed-up feathers, unmoving on the ground under the mesquite tree, I wondered if there was a behavioral pattern I’d missed. The youngster didn’t move when I walked out and sat on a nearby bench, but eventually, it woke up and flew up to a neighbor’s roof. I went back to my drawing table, but an hour later, I saw a few people standing around the bird as it sat on a cement entryway. Something wasn’t right. I put the bird in a carrier, and rode with my neighbor to the Tucson Wildlife Center.

As the engine of her vintage sports car loudly rumbled, on what seemed like an endlessly long trip, I thought about the acuity of the bird’s hearing, and wondered if the reverberations along with the trauma would be too much for this little creature to bear. Despite its built-in protection, the woodpecker died 15 minutes after we arrived, probably due to internal injuries from a window strike.

I returned home to find another fledgling and its parent inspecting my newly planted barrel cactus. While I don’t put out bird seed, when it comes to the critters, I live to serve. For the almost three years I’ve been in Tucson, I’ve been filling the watering holes and keeping the sugar bar open, happily accepting my role as barista to the local wildlife.

One of my rewards, is being able to listen to the Gila woodpeckers talk as they tip the feeders and drink in the sweetness of life.

Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.