When you touch it, it gets worse

Up a flight of concrete stairs in Bisbee, with a view of grassy hills, dotted with houses, sits a reservoir. The water is dark, and there’s a giant yellow pipe that dips into it like a straw.

Logan Dodd from the city’s public works department and a few others walked up there with me.

"We are up at the top of the reservoir for old Bisbee," he said. "This is what feeds our gravity fed fire suppression system."

He told me the problems in this reservoir eventually work their way down to the fire trucks and hydrants.

“As you can see, it's exposed to elements. So dirt, debris, critters go into there. There's a fish habitat in there right now,” he said.

But that’s not intentional. Fish get here from people dumping old pets.

The people I talked to won’t admit to doing it themselves, but high schoolers have been sneaking in after hours to swim and hang out for generations. And this is where the water used to fight fires in Bisbee comes from.

VIEW LARGER A reservoir sits high in the hills of Bisbee. The water here goes to fighting fires in town, and city officials are looking to replace it with a more up-to-date system.

VIEW LARGER A reservoir sits high in the hills of Bisbee. The water here goes to fighting fires in town, and city officials are looking to replace it with a more up-to-date system. A school of orange fish swam towards me and Jim Richardson, the fire chief.

"I don't know if they're goldfish or koi fish, but either way, they'll probably get big," He said.

Sometimes, a firefighter will find one in the truck when they pump the water through.

"Every year we're supposed to, to open and flow our hydrants to to get out the sediment," Richardson said. "But the community complained so much about the smell of the water that comes out of the hydrants."

Only a few things are so basic that life cannot exist without them, and water is one. We cannot grow food or raise livestock without it. Sustained drought leads to loss of trees and plants, and the wildlife that rely on them.

Lack of water promotes destructive wildfires, causing irreversible damage to the environment and the places we call home. It also wreaks havoc on our economy - stymying business growth and the development states like Arizona count on. And perhaps worst of all, competition for this limited resource divides us.

The damage of a drought can be devastating. But, it doesn't have to be. Solutions are possible, and in some places, already in the works.

The City of Bisbee in Southern Arizona still relies on a lot of things that were built almost one hundred years ago, as part of the New Deal. That includes the water system it uses to put out fires, which needs major updates.

So, how does a small western town make that happen, and what are the risks if the project doesn’t come through?

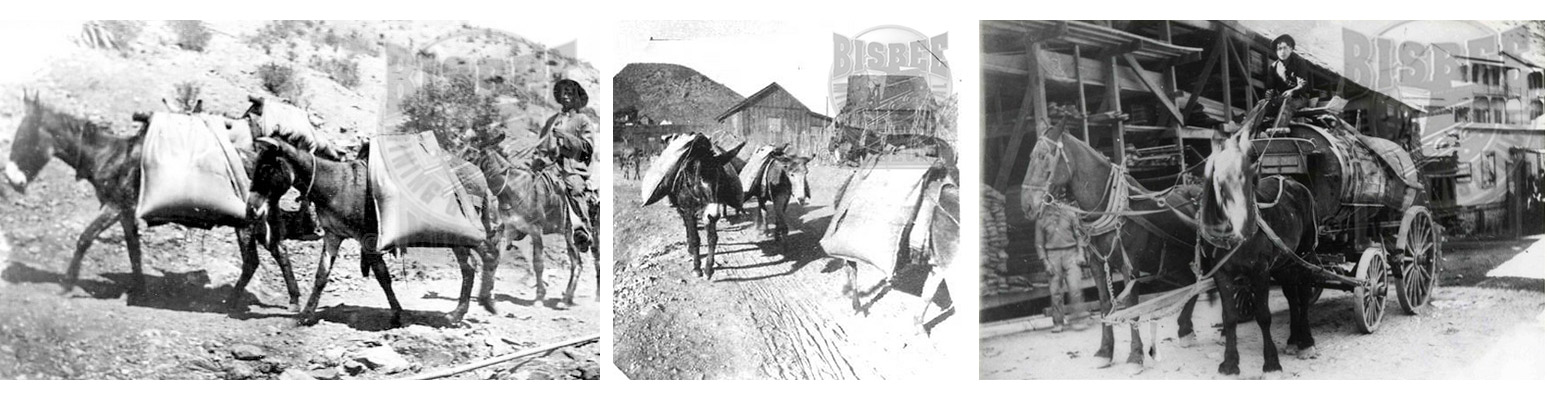

LEFT AND CENTER: Burros carrying water bags in Bisbee. Circa 1899-1900. RIGHT: Horses pulling a wagon of water down the street.

LEFT AND CENTER: Burros carrying water bags in Bisbee. Circa 1899-1900. RIGHT: Horses pulling a wagon of water down the street.

In 1979, Carl Nelson gave an interview to the Bisbee Council on the Arts and Humanities. He had lived in Bisbee since about 1903. His father was sent by a St. Louis company to sell tools, and he brought his family along.

He recounted how he and his family adjusted to the change.

“My mother didn’t like it at first. And she cried for the first week,” he said. “But she finally became accustomed to the place and liked it a whole lot better. ‘Course, one thing, she didn’t like the water systems they had here, which really they had no system, just a well.”

At that time, there wasn’t a water company in town. So, families like Nelson’s who lived lower in the canyon had wells, but those up in the hills had to make other arrangements.

"This water was delivered by burros, carrying two large sacks, bags, one on either side," he said.

Bisbee used to be a major player in mining, and the biggest game in town was the Copper Queen. Mining companies also dug wells in the area, and the Copper Queen had one in nearby Naco. They needed a lot of water – copper smelting takes a lot.

The city grew, and the mines, residents and water deliverers kept pumping. In 1903, the supply in town started to run low. They called it a “water famine” at the time.

But the Copper Queen’s supply in Naco was really reliable, and some businessmen bought their well and pipeline along with a plant in town and created a company, the Bisbee-Naco Water Company, to get water to residents.

That company is still the main water provider in town – now called the Arizona Water Company – and the city still gets its water piped in from the same area.

A few decades later, the mining companies took a hit with the Great Depression. Production slowed. The population declined. And the infrastructure wasn’t kept up.

VIEW LARGER A nearly 100-year-old pumphouse in Bisbee.

VIEW LARGER A nearly 100-year-old pumphouse in Bisbee. But then, Bisbee got a transformation.

The Works Progress Administration funded lots of projects in every corner of the country. From roads to bridges to airports to water.

Water infrastructure throughout thousands of cities and towns, including Bisbee, saw expansion with the construction of reservoirs and water supply systems.

The fire department still uses the pipes, pumps and reservoirs the WPA put in more than 80 years ago.

The Works Progress Administration’s impact didn’t end there. Bisbee still has paved roads, ditches, dams, the Copper Miner statue, remnants of a public swimming pool, a golf club, a baseball grandstand, stairways through neighborhoods, sidewalks with USA WPA stamped on the corner and more.

It injected a lot of life back into the town, but in the decades since, there hasn’t been that same kind of money to maintain some of those projects. And that included the water system the fire department relies on.

Downhill from the reservoir in Bisbee, there’s a pumphouse. Several town leaders, public works employees and the fire chief met me there.

Before we went in, a couple women on a walk stopped to thank the fire chief. I was there in mid-April, the morning after the third wildfire of the season, which came early.

"The winds are picking up later right?" one woman asked, and Richardson said yes.

"Is that gonna be problematic?" the other woman asked.

"We’re surrounding it now," Richardson said.

We went inside the pump house. It’s an old, gray building with rust-red trim.

It was dark and dusty inside, and the pump was so loud, they had to turn it off for us to talk.

The water delivery system didn’t cause a problem that night, but it’s been a problem for some time.

Ken Budge is the mayor and knows the system well - he's a retired firefighter.

“Every time you touch anything old, it just starts to fall apart on you. This is just what happens with an aging structure. You know, like any plumbing in an old house,” he said.

The longer something like this sits, the worse it gets.

“An example of a good failure would have happened to Moon Canyon Fire, or Star Avenue, even worse.

VIEW LARGER A ruptured pipe in Bisbee.

VIEW LARGER A ruptured pipe in Bisbee. "One of the lines ruptured, I have a picture of it – a big split right down the side shot all of our water up in the air and we had to go back up the canyon and pull a hydrant from almost a full hose length of everything the truck had to get that water back up to the fire.”

And he said it's going to happen again.

"We're sitting here just waiting for the next failure, and we don't want to touch anything because when you touch it, it just starts cascading and gets worse and worse and worse."

There’s the pungent smell of the hydrants when they flush them.

And Adrian Borquez with the public works department says leaks are an issue.

"There's valves throughout the city. Half of them don't work," he said. "So, to isolate a leak, sometimes you have to shut half the city down, just to get to one leak on one street. Whereas if the valve would work, you would just shut the one street down."

Then, there’s the fish.

"We've had catfish in our fire truck strainers," Richardson, the fire chief, said. "As the hose goes into the fire truck from the hydrant, we have a screen, uh, and you pull out catfish, pull out sticks, rocks."

A few years back, the Environmental Protection Agency told Bisbee they’d need to scrap the whole potable system.

Bisbee resident Danielle Bouchever works for a local non-profit, and writes grants for the city as a volunteer. She has worked on projects from infrastructure to housing.

She said they came up with a plan to work with the Arizona Water Company to expand their potable water system and build new tanks, lines and 110 hydrants.

VIEW LARGER Firefighters hold the line along a highway in Bisbee

VIEW LARGER Firefighters hold the line along a highway in Bisbee "That would bring us up to code as far as pressures go. We would have consistent pressures throughout the city, which we do not have currently," she said. "We would have much more stored water above ground, and we would have twice as many fire hydrants as we currently have."

Bouchever lives near where a fire happened the night before.

“The team was able to keep that line, but they were definitely embers coming over into the town side of the highway,” she said. “Along that edge, there are not enough fire hydrants with enough pressure to be able to fight that, especially if it started to get into our structures, because then you've got big embers that continue.

And we're cheek to jowl in this town. We're on the hillside."

The plan they have would go a long way, but it still costs money and time. So, they applied for a FEMA grant and they’re still waiting to hear back.

Mark Apel is a retired University of Arizona researcher, where he worked on water issues. He’s now the environmental projects coordinator for Cochise County and spends a lot of his time on the San Pedro River.

He’s also been a resident of Bisbee for 25 years. He said climate change isn’t just making fire season longer and more destructive. It also affects the water supply in town, as the aquifer levels have begun to change more dramatically.

“We have a well in my neighbor's backyard very close to this pump house, and that is essentially the water level of the aquifer," Apel said. "The groundwater in that area that is being drawn upon to fill that reservoir, and it changes. It can drop 12 feet over a few months, depending on whether we've had rains or not.

"This winter, the water levels are pretty low in the aquifer right now down there, I can look right down to my neighbor's well and see where the water is. And that water supply is somewhat tenuous."

The system run by the Arizona Water Company draws water from a different source – the Upper San Pedro Basin – and that source is more reliable.

Apel said he’s hoping that if the city can get the grant and expand the potable system to provide fire suppression capabilities, it will give himself and other residents a little more breathing room.

If you live in a fire-prone area, you know putting one out isn’t all about hosing it down. Firefighters clear brush. They use fire retardant. They also work on preventing fire, and that usually takes some help from homeowners in the area.

Apel lives in what’s called a wildland-urban interface. His backyard is wild lands. There are neighbors to either side but his property backs up to hills, grasslands and a stead of oak trees.

"So the threat of wildfire is really high and damage to residences is very high," Apel said.

The city works with people in Apel’s part of town to clear brush and make updates that would help prevent a fire from spreading through it.

"There's quite a bit of responsibility that should be taken by homeowners to make sure that the fire department's not taking care of fires due to neglect around somebody's house." Apel said that includes storing pallets or stacking firewood up against a house.

But water is still a big part of the equation.

“If we didn't have water, we'd be seeing a lot of damage in Bisbee due to wildfires, or residential fires," Apel said. "But thanks to our stellar fire department and Arizona Water, we do have a supply of water,” referring to the pumphouse and hilltop reservoir.

"And right now, that is the only source of fire suppression water in our neighborhood up there," he said.

So how does a small town get a federal grant for a project like this?

"There's a lot of money out there, but there's a lot more to a grant than most people think," Apel said. "Many rural communities throughout the West aren't really equipped to apply for those grants, they don't have grant writers, they don't have the administration to oversee the grants and the finances of the grant, etc."

Bisbee’s grant application was a lift in itself and was led by Danielle Bouchever, a volunteer, which is who a lot of small towns rely on when they can’t afford much staff. Apel said Bisbee is lucky to have her, but not every town has someone like her.

"We're really lucky to have somebody like Danielle, to help our city. But there's not somebody like her in every town, or people like her who have that training and have that experience with applying for grants," Apel said.

And if they do get the grant, the project could still be messy. He said in an old town like Bisbee, there are probably things underground they won’t be expecting.

"When we got a grant from USDA to put in a new sewage system, they were digging up old redwood boxes that were serving as sewer lines from the early days that were still supposedly conveying sewage," he said.

"Those all got replaced with new pipes, so I imagine that's what's going to happen when they start to dig into the water delivery system."

But it will help secure the town as wildfire becomes a greater threat to Bisbee.

"When it's wildfire, you have the hills burning above you, and you want to be sure that the fire department has all the resources that they need to be able to prevent that fire from coming down into town, or to be able to attack it once it's anywhere near any of the residential structures. Having a system in place that gives them ample supply to attack that fire, and to protect our homes, is huge.

They need the grant to fix the system. Otherwise, Bisbee’s stuck with a system that gets worse by the day.

They expect to hear back about the grant, and their future, in the fall.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.