The vaquita is a critically endangered porpoise that lives in the northern part of the Sea of Cortez. It is considered the smallest and most endangered cetacean in the world.

The vaquita is a critically endangered porpoise that lives in the northern part of the Sea of Cortez. It is considered the smallest and most endangered cetacean in the world.

The vaquita marina, or "little sea cow" in Spanish, is considered the world’s most endangered marine mammal.

The gray porpoise — known for its small size and characteristic black markings around its eyes and mouth — only lives in the northernmost part of Mexico’s Gulf of California, where fishing has brought the species to the brink of extinction.

But research now finds that, genetically speaking, there is still hope the vaquita population can recover.

“We’re really pushing back on the idea that the species is doomed,” says Jacqueline Robinson, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of California, San Francisco and an author of the study, which is published in the journal Science.

While all future vaquita will be descendants of just an estimated 10 remaining porpoises, the study shows that the negative impacts of inbreeding would be minimal. In fact, Robinson and her team found the species would have a good chance of recovering — if it can be better protected from gillnets, walls of netting submerged underwater that can trap and drown the small mammal.

Predicting the vaquita’s chance of survival

The study’s authors note that vaquita populations have historically been small. That means there’s actually little genetic variation between the porpoises, which tend to weigh about 100 pounds and can grow about 4 to 5 feet long.

“The fact that they’ve had low population sizes and low genetic diversity for a very long time in their evolutionary history kind of gives them an edge for rebounding from this current extreme population decline,” Robinson says. “They have less hidden, harmful genetic variation that could become a problem with future inbreeding.”

To understand the vaquita’s chances of recovery, the researchers started by sequencing and analyzing 20 vaquita genomes taken from archival tissue samples. The species’ genetics helped researchers understand the vaquita’s history and its past population size, which they estimate remained under 5,000 for tens of thousands of years because of its restricted habitat.

The recent dramatic population decline is largely due to vaquitas being ensnared in fishing nets, which are often set up by poachers in the waters of Baja California to catch totoaba — a huge endangered fish that’s extremely lucrative on the black market in China where it’s sold for its swim bladder.

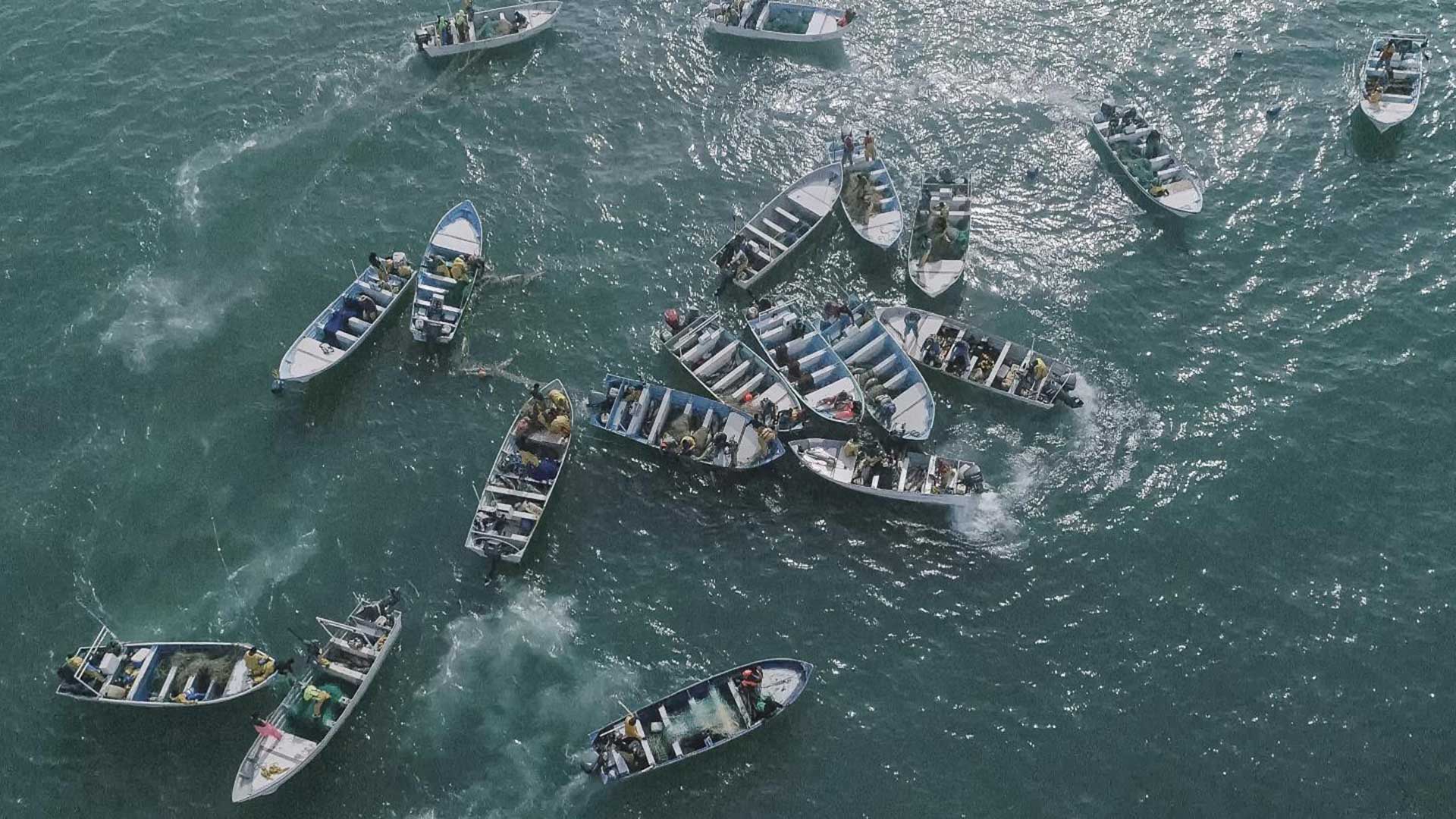

More than 80 small fishing boats illegally cast nets into the Sea of Cortez in an area inhabited by the vaquita marina porpoise on Dec. 8, 2019.

More than 80 small fishing boats illegally cast nets into the Sea of Cortez in an area inhabited by the vaquita marina porpoise on Dec. 8, 2019.

The study drew on their genetic analysis and what’s known about the vaquita’s biology — its lifespan and reproductive behavior — to model population growth or decline assuming different levels of gillnet deaths.

If those deaths stopped entirely, the scientists only found a 6% chance that the vaquita would go extinct in the next 50 years, based on simulation estimates. But if fishing continues to kill off the animals, even at significantly reduced levels, the likelihood of extinction increases dramatically.

“Our results show a major impact of the gillnet mortality rates,” says UCLA researcher and study co-author Chris Kyriazis, who developed the team’s simulations. Even with an 80% reduction in gillnet deaths, chances for the species’ survival plummet, he says.

Robinson says their research shows that genetic diversity is not the problem for the endangered porpoise and that humans can intervene to keep them from vanishing.

Without the pressures of harmful fishing in their habitat, “there is a very good chance that vaquitas would rebound on their own,” she says. “And that is what has not been happening so far.”

Enforcing ‘zero tolerance’

Stopping harmful fishing practices has been a long-term struggle in the Upper Gulf of California.

Regulations to protect the vaquita marina have been on the books for decades in Mexico, and there is a zero-tolerance zone in the area considered most critical for the little porpoise, where gillnet fishing is prohibited. But enforcement of those rules is lax.

“The vaquita’s population won’t recover without protection,” says Alex Olivera, senior scientist and Mexico representative for the Center for Biological Diversity. “We need more enforcement from the Mexican government.”

Despite pressure from conservation groups, the U.S. government and international organizations, Olivera says Mexico has failed to adequately protect the few remaining vaquita.

This new study on the genetic viability of the species shows there is still time to act, he says: “This adds to the argument that the species can be saved, they can recover, even though there are only a few individuals left.”

UCSF’s Robinson says their research makes it clear that the recovery of the vaquita ultimately depends on keeping the waters where it lives free of fishing nets. And while past efforts have been insufficient, she’s still hopeful.

“I think the takeaway is not to write off a species because it has low genetic diversity, or to say it’s doomed. That’s an assumption, and it’s probably a flawed one,” she says.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.