Water in the Rillito River following a monsoon storm. July 23, 2020

Water in the Rillito River following a monsoon storm. July 23, 2020

In June, the Trump administration's new version of which waters are protected under the Clean Water Act took effect. The new rule is an about-face from the Obama-era regulations, and Arizona state regulators are trying to make sense of it.

The Trump administration significantly narrowed the definition of what qualifies for protection under the Clean Water Act, which means the majority of waterways in Arizona--those that flow only after rain or snow--no longer get such protection.

The new rule stipulates that "relatively permanent waters" that are perennial or intermittent but connect to a traditionally navigable water, like a river, are protected. But defining which waterways are permanent enough is proving tricky, especially since the federal government hasn't provided the data for that yet.

The new Navigable Waters Protection Rule does require Clean Water Act permits for point-source discharges to waterways that are protected, known as "waters of the U.S." That means, for example, that a power plant that discharges into the Colorado River needs a permit. But, in an example provided by ADEQ during an informational webinar, the Kingman-Hilltop and Willcox Wastewater treatment plants don't need permits because they don't connect to any relatively permanent waterways.

VIEW LARGER A map of flow regime designations created by ADEQ to help clarify which waterways in Arizona still require protection and permits under the Clean Water Act. As of mid-September, the status of 80% of the state's streams are still undetermined.

VIEW LARGER A map of flow regime designations created by ADEQ to help clarify which waterways in Arizona still require protection and permits under the Clean Water Act. As of mid-September, the status of 80% of the state's streams are still undetermined. Arizona's Department of Environmental Quality is trying to make the process a bit clearer for those who hold Clean Water Act permits in the state. Part of that work involves creating a map of the so-called "flow regime" of all the waterways in Arizona, using data from multiple sources. Flow regime is basically how much water is in a given stream over the course of the year, and is supposed to be based on a 30-year average of data. Still, about 80% of stream segments on the ADEQ map don't have defined flow regime yet. ADEQ said they will continue to work on the map and expect some additional federal guidance from the Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers, though those departments have not said when they will release such tools.

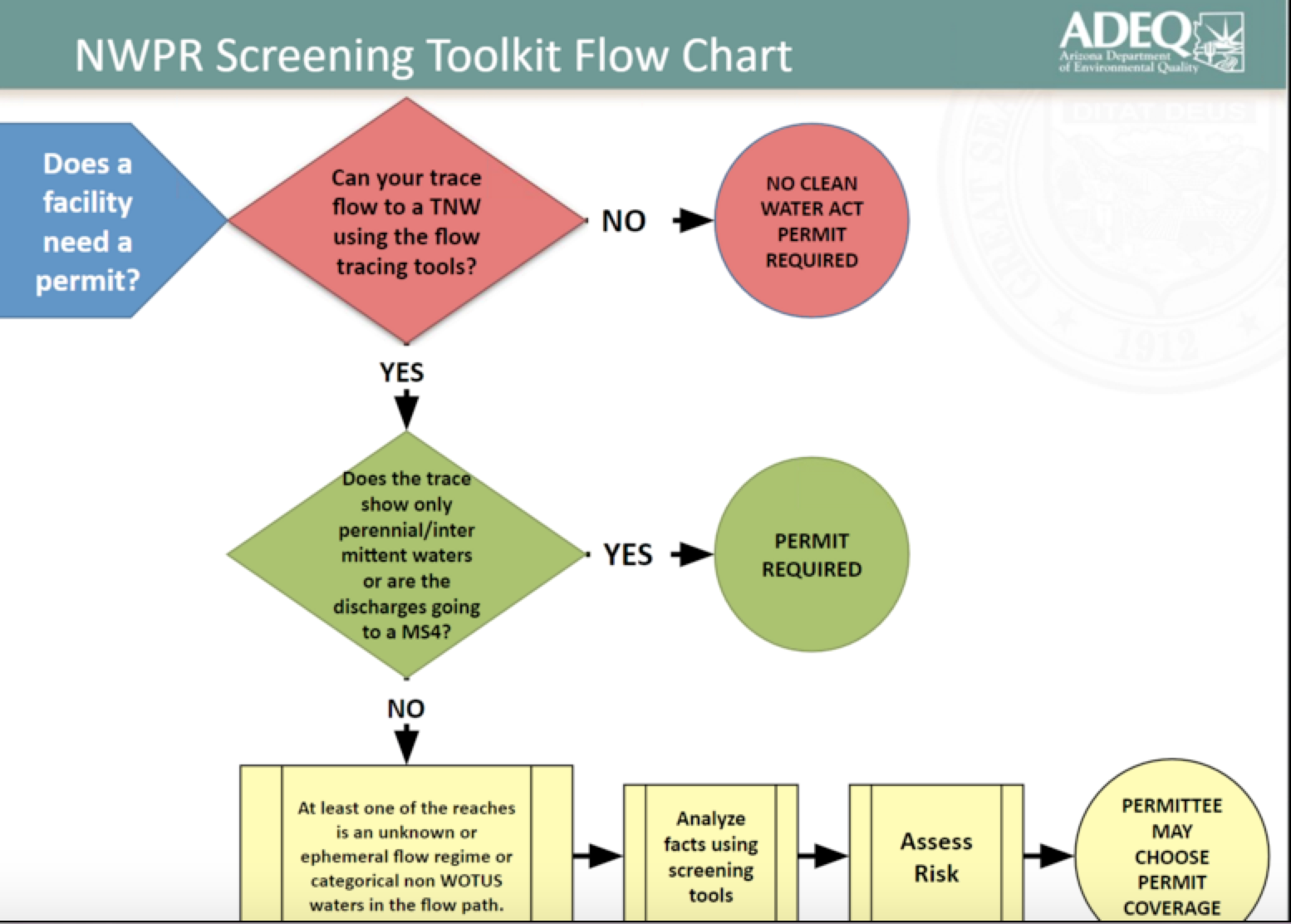

ADEQ has also developed what they're calling a "tool kit" to help permit-holders decide whether they need a Clean Water Act permit under the new rule. The department is also working on a state-level set of surface water protection regulations, which it currently lacks.

Pima County Regional Flood Control District is regulated by the Clean Water Act and ensures compliance with the federal law. For its part, the district is continuing to operate under the regulations in place before the rule change, according to Director and Chief Engineer Suzanne Shields.

"And the reasons why we're doing that is because say I start designing a project and I need a 404 permit from the [Army] Corps [of Engineers] for disturbance of 'waters of the U.S.' It may take me two years to get the project designed. And there's already been some lawsuits filed on this definition of waters so I can't take the risk of getting to the end of the two years and then suddenly it is a regulated water," Shields said.

She said one complicating matter in terms of gathering data for Pima County is that most rivers like the Rillito or Pantano are so wide that stream gauges don't catch small flows, because they're set to register floods like those after monsoons.

The Santa Cruz River from Camino del Cerro downstream to the county line is defined as a traditionally navigable water, Shields said. "But then my question would be, is something like the Rillito and Sabino Canyon, that flow fairly regularly, are they also 'waters of the U.S.' or not? And there's no way I can answer that question, let alone any of the other ephemeral streams."

Shields said ADEQ is expecting permittees like Pima County to determine whether streams are "waters of the U.S." or not, even though she said locally they don't have the authority to make those decisions. Her department will continue to follow the determinations of the Army Corps of Engineers.

ADEQ said in an email that "like other regulations, such as the Clean Air Act or building codes, businesses can decide if they will apply for a [Clean Water Act] permit, however, if they do not obtain a permit and ADEQ or EPA determine the facility is subject to the CWA, any appropriate compliance and enforcement action would be taken." ADEQ did not make anyone available for an interview.

VIEW LARGER A flowchart taken from ADEQ's "tool kit" to help permit holders know if they still need a Clean Water Act permit under the new rule authored by the Trump administration which took effect in June 2020.

VIEW LARGER A flowchart taken from ADEQ's "tool kit" to help permit holders know if they still need a Clean Water Act permit under the new rule authored by the Trump administration which took effect in June 2020. Shields said other industries she regularly works with, like construction and mining, also seem to be staying the course of permitting prior to the Trump administration's rule change, because so much uncertainty remains and violating CWA protections can be quite risky. She said this rule change has also complicated the county's storm water system permit process.

"I've been working in this industry since 1976 and the definition of Clean Water Act regulations, especially what is a 'waters of the U.S.,' it's just a revolving door. It's changing constantly and I think this change makes it even more unclear and more uncertain as to what's being regulated and what's not," Shields said.

Several lawsuits have already been filed against the Trump administration's rule.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.