In August of 2003, Matei Georgescu’s parents moved to Arizona. At the time, their Glendale home stood on the edge of Phoenix’s sprawl, close to the rugged mountains and low-lying brush that pockmark the desert.

Georgescu, who was born in Romania, had immigrated to the eastern coast of the U.S. with his parents when he was 8 years old and had lived there since. He had known colder, greener places, and was struck by the desert’s weird beauty.

But just a few months later, when Georgescu came home for the holidays, the desert was much farther away.

“My parents were no longer at the edge of town,” he recalls. “It was clear that something interesting was happening in Arizona.”

Georgescu, a climate scientist, became intrigued by how quickly Arizona was growing and developing, and what that might mean for the state’s future—and, more specifically, for its weather.

Urban development is known to heat things up, thanks to what’s called the “urban heat island effect.”

Blacktop roads, cement sidewalks and buildings all heat up more dramatically in the sun than soil or plants do, causing the air around them to heat up too. They also release the heat they absorb well into the evening, preventing the air from cooling as night falls. As a result, cities tend to be hotter than rural areas.

Georgescu wondered how these climate-altering effects would play out over 40 or 50 years of growth in Arizona’s Sun Corridor, the fast-developing span of desert that starts in Prescott and swoops south to Nogales. How hot could it get?

To answer that question, Georgescu and his collaborators turned to a few different projections of the Sun Corridor’s growth, including projections from the Maricopa Association of Governments. Using a number of sources—Census data, employment data, birth and death records, land ownership records and data on land use patterns, applications for housing permits and drivers’ licenses, and even school enrollment rates—these projections try to piece together a picture of growth over the decades to come.

Georgescu turned up a conservative scenario that would put Arizona’s population around the 8 million mark by 2050 (it’s currently 6.4 million), and a high-growth scenario that projects as many as 16 million people will live in the state by 2050.

Then, using simulations that can mathematically represent everything from roofs and roads to the changes in vegetation as plants bloom and wilt through the seasons, Georgescu modeled the urban heat island effect for each scenario.

He found that the highest-growth scenario would heat up the state’s summers by as much as 4 degrees Celsius, or about 7 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s independent of climate change, which is also expected to raise Arizona temperatures.

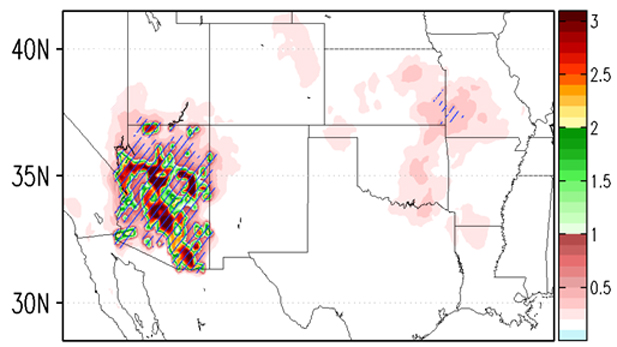

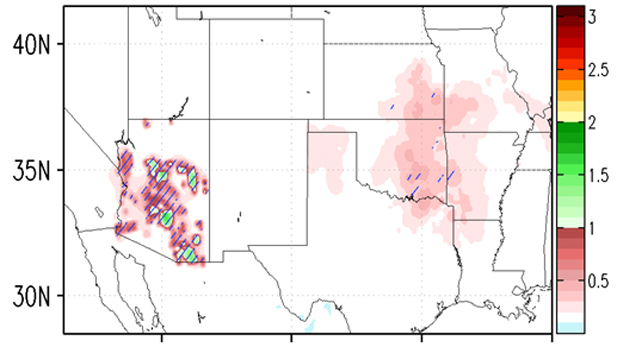

In Georgescu's highest-growth scenarios, temperatures in Arizona could rise as much as 4 degrees Celsius (about 7 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2050 due to the urban heat island effect alone. As shown in the map, that warming would also affect climate conditions in the central U.S.

In Georgescu's highest-growth scenarios, temperatures in Arizona could rise as much as 4 degrees Celsius (about 7 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2050 due to the urban heat island effect alone. As shown in the map, that warming would also affect climate conditions in the central U.S.Even the more conservative growth scenario would warm things up, yielding a temperature increase of about 1 to 2 degrees Celsius, or 2 to 3 degrees Fahrenheit.

“The magnitude of the warming definitely surprised me. It’s pretty considerable warming,” says Georgescu.

Even Georgescu's lowest-growth scenarios, which conservatively project about 8 million people in the state by 2050, show warmer temperatures due to the urban heat island effect.

Even Georgescu's lowest-growth scenarios, which conservatively project about 8 million people in the state by 2050, show warmer temperatures due to the urban heat island effect.The study, published in Nature Climate Change this week, also indicates the warming would affect climate conditions in the central U.S.

Rising temperatures would change life in Arizona in significant ways, says James Buizer, deputy director for climate adaptation and international development for the University of Arizona’s Institute of the Environment.

“We’re used to having a certain temperature and an average of eight to nine inches of rain in Arizona,” Buizer says. “If our new reality is hotter or it’s having six to seven inches, we need to make some changes.”

A hotter Arizona would mean more demand for air conditioning and other temperature controls, which would in turn mean higher electricity costs. If the heat altered water or food supplies, it would translate into higher costs for those resources too.

“Places like Riyadh regularly get 130 degrees [Fahrenheit] in the summer, and people have lived there forever,” says Buizer, so higher temperatures wouldn’t make Arizona uninhabitable. But it could make living here prohibitively expensive for the state’s lowest-income residents.

Limiting the climate impacts would require rethinking development, Buizer says. Designing developments that preserve open space or planting more trees could keep the desert cooler.

Georgescu’s study points to another potential adaptation: painting roofs white. Just taking that step would significantly reduce the warming effect, Georgescu’s models show.

But whatever happens—and however hot it gets—Georgescu isn’t planning to leave Arizona anytime soon.

“Oh, I’m not going back to cold weather,” he says. “I wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.”

--

The Fronteras Desk series Heat Wave further explores the human cost of rising temperatures. Read it here.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.