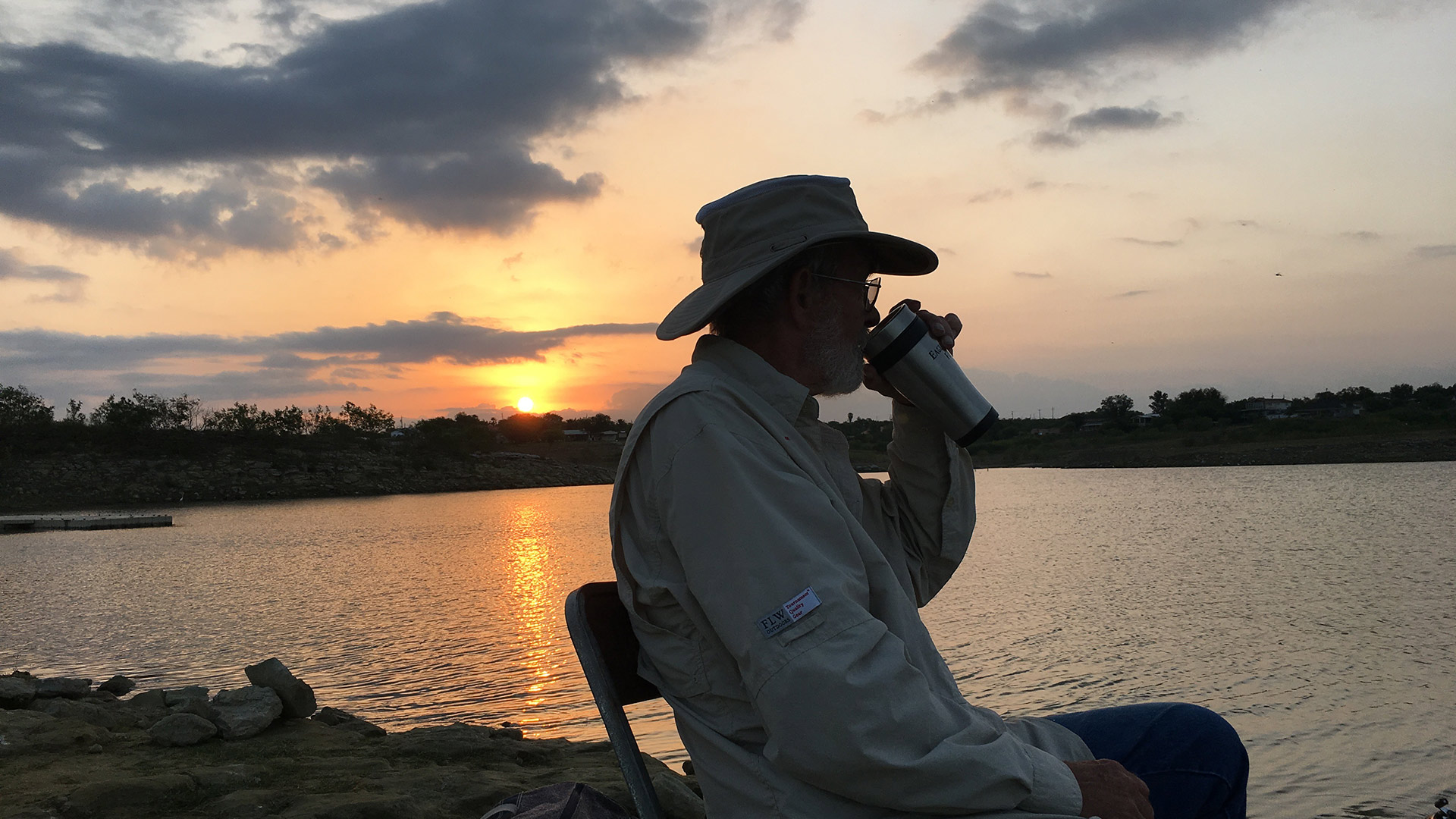

David Loftis fishing for bass from Falcon Lake in Zapata County, Texas. He said he'd move if the United States needed him to in order to build a border wall.

David Loftis fishing for bass from Falcon Lake in Zapata County, Texas. He said he'd move if the United States needed him to in order to build a border wall.

This is Part II in a special four-part Fronteras Desk series about the U.S.-Mexico border and the challenges border residents and U.S. immigration agencies face as President Donald Trump completes his first 100 days in office.

Chris Bauer’s family has been farming the eastern corner of Texas for 100 years. And he’s been fighting to keep that tradition going for the last decade.

"I grow sugar cane. I grow corn, cotton, green sorghum and I have some cattle," he said, gesturing toward the velvety green 1,000-acre farm that starts right off the highway just behind his steeply pitched house and travels back for a mile, ending in a clump of trees on the banks of the Rio Grande.

VIEW LARGER Chris Bauer had land seized so the U.S. could build the border wall under the Secure Fence Act of 2006. He still hasn't been paid.

VIEW LARGER Chris Bauer had land seized so the U.S. could build the border wall under the Secure Fence Act of 2006. He still hasn't been paid. The official boundary between the United States and Mexico lies in the river but you wouldn't know from looking at the giant concrete and steel structure that chops his land in two and serves as the United States border wall.

Land from Bauer's farm was seized in 2008 when the U.S. developed plans for a border wall that would then satisfy the Secure Fence Act of 2006.

"There’s no sense in fighting it; they’ve got a lot better lawyers and more money than I’ve got," Bauer said.

He first heard of the government's plan by a letter in the mail from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

The government seized two acres and appropriated several more to build a road. Bauer was left with a levee behind his home with an added steel bollard wall on top of it. Then a road was added on top of the levy and, finally, a gateway but no gate. All of this created a headache for Bauer, who kept his sense of humor even as he lost his land.

VIEW LARGER This levee with a border wall on top of it was built on Chris Bauer's home in Cameron County, Texas, 2008.

VIEW LARGER This levee with a border wall on top of it was built on Chris Bauer's home in Cameron County, Texas, 2008. Most farmers whose land was taken for the border fence then received a gate with a personal code. Bauer said he's still waiting for the gate.

And for other details.

"They pay for two acres but they take 15 or 18 acres. Then they still haven’t paid for the two acres," he said.

Bauer said he’s owed about $15,000 for the land grab. And he figures the land south of the border fence is now worth half its original value, down to $2,000 an acre.

He voted for President Donald Trump, saying he liked the promise of limited involvement in foreign affairs. But Bauer’s not optimistic about his chances of ever getting compensated for his land.

"Whatever, it’s been a long time so they may have forgotten about it by now," Bauer said. "And it’s not gonna go to me. It’ll go to my family. Eventually we’ll be compensated. In the meantime we keep working, keep producing, keep going forward."

VIEW LARGER A memorial to the U.S.-Mexico International Water and Boundary Commission commemorates the Falcon Lake Dam that separates the two countries here.

VIEW LARGER A memorial to the U.S.-Mexico International Water and Boundary Commission commemorates the Falcon Lake Dam that separates the two countries here. Emma Hilbert is an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project.

The nonprofit is looking for future cases like Bauer’s as the new border wall goes up around the Rio Grande Valley and El Paso.

Hilbert said there’s two fights to wage.

"One is the actual taking. Arguing that the government shouldn’t take the land at all. That’s the harder piece to fight, because the government can take land for quote-unquote public use, and putting up a border wall and calling it a national security issue is arguably a public use," Hilbert said.

The second is making sure landowners get paid.

"If the land’s going to be taken, you at least get what it’s worth," she said. "And that’s going to be higher than what the government has offered originally."

About 150 miles down the road, the massive Falcon Lake acts as its own border. The air is thick with the smell of rotting fish on the shore and the morning silence is broken by a Border Patrol boat about to head across the still surface of the water.

"There’s no sense in fighting it; they’ve got a lot better lawyers and more money than I’ve got" - farmer Chris Bauer

David Loftis was fishing for bass from the banks. He lives in a neighborhood of homes built around the lake. It’s not clear whether a wall would go up in the water, north of the lake - leaving U.S. homes south of a border wall- or not at all.

"Don’t matter to me, I could always get up and move," he said.

Like Bauer, he voted for Trump and said stopping illegal immigration is more important than being bought out.

"He’s gotta do it. Whatever has to be done. Nobody else is stopping it. It’s got to be stopped," Loftis said.

VIEW LARGER A sign warns people to be cautious in Falcon Lake. In 2010, a U.S. citizen on a jet ski was murdered by a shot from the Mexican side of the giant lake.

VIEW LARGER A sign warns people to be cautious in Falcon Lake. In 2010, a U.S. citizen on a jet ski was murdered by a shot from the Mexican side of the giant lake. Across the lake dam that serves as the border crossing into Guerrero, Tamaulipas, Mexico, Narcisso Martinez turned off his weedeater to talk about the border wall.

"The wall will hurt more than benefit an already tense situation," he said in Spanish.

In its 2018 budget request, the Trump administration asked for funding for 20 new attorneys to take on landowners who choose to fight the government’s border wall plans. What isn’t known yet is whether the government will settle its old land-seizure debts like Bauer’s before it starts taking new ones.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.