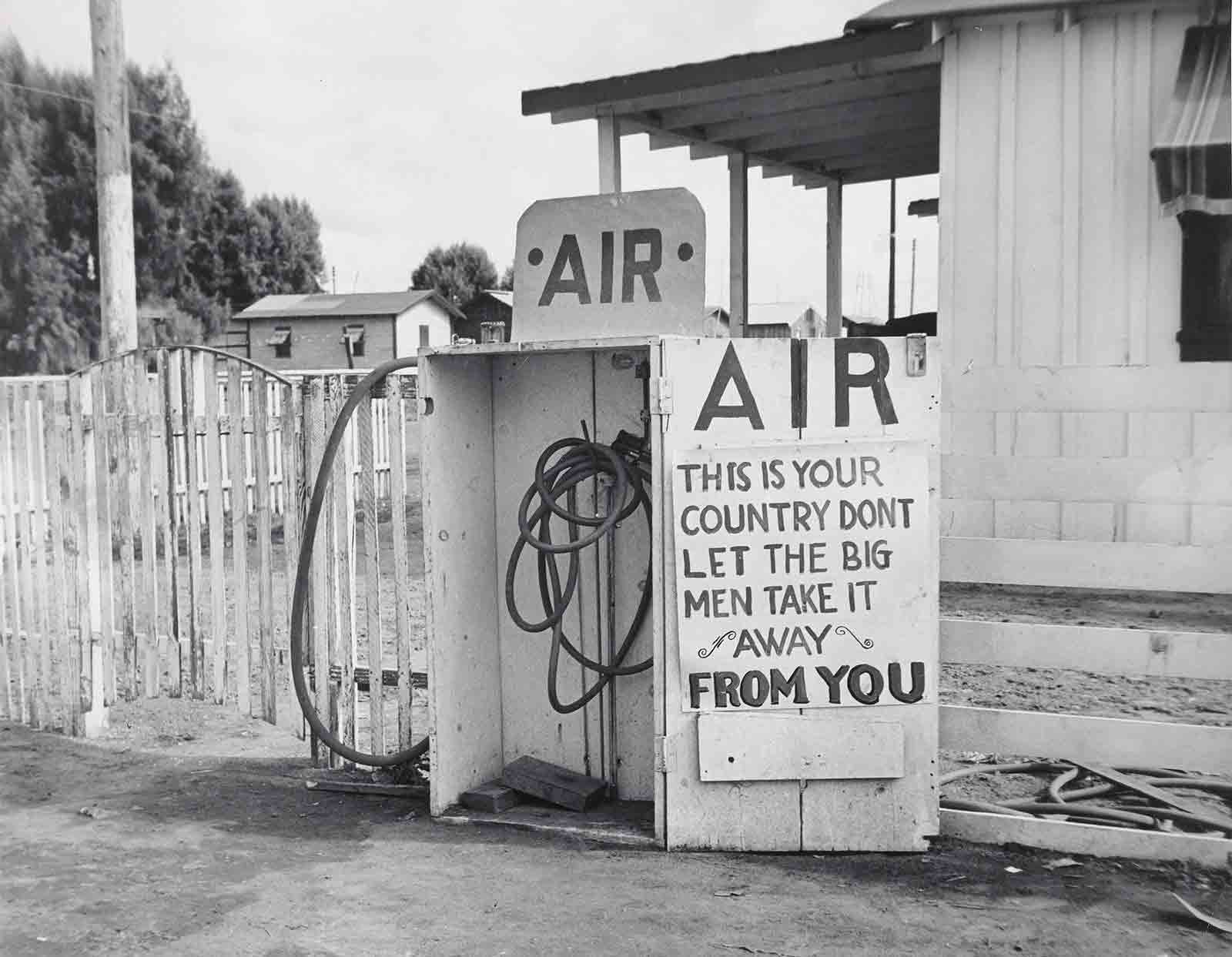

VIEW LARGER Dorothea Lange's <em>Kern County, California (1938)</em>. The photographer's most famous work came while she was working with Depression-era federal programs, seeking to document the human fallout of the great economic collapse.

VIEW LARGER Dorothea Lange's <em>Kern County, California (1938)</em>. The photographer's most famous work came while she was working with Depression-era federal programs, seeking to document the human fallout of the great economic collapse. But she also took notes — lots and lots of notes, scribbling constantly as she worked: recording how her subjects spoke, what they were doing to get by, why their lives took shape as they did.

"I went out just absolutely in the blind staggering, as something to do," Lange herself said in interviews conducted over 1960 and '61 and preserved by the University of California, Berkeley's Oral History Center. "Well, I really kept to it."

Those notes helped inspire a retrospective of Lange's work at New York City's Museum of Modern Art, which opened in mid-February ... and promptly closed less than a month later because of a different kind of crisis, the coronavirus pandemic.

"The installation views are there. The pictures are hanging in the dark," says Sarah Meister, the exhibition's curator. "And now it's like, 'OK, so then what?' "

So, Meister and her colleagues decided to relaunch the exhibition as a weeklong, entirely online experience — including views of the installation, a live Q&A and some added video and podcast segments. That project, which goes live Thursday, also offered an opportunity to reframe some of Lange's work in light of the tumult caused by the pandemic.

She points to one piece, in particular.

"Her photograph from 1938 about unemployment aid beginning. It's this line of men in hats standing very close together. It's just this very self-enclosed, sad, desperate plodding, hopeless kind of picture," she recalls.

The echoes with today's desperate unemployment landscape are inescapable. More than 30 million people — or 1 out of every 5 people who had a job in February — have filed for unemployment in the past six weeks alone, as the coronavirus and widespread lockdown efforts take their toll. The U.S. economy may see its sharpest economic downturn since Lange's own day, during the Great Depression.

VIEW LARGER Dorothea Lange, <em>White Angel Bread Line, San Francisco</em> (1933). Sarah Meister, MoMA's photography curator, sees new resonance in Lange's photographs of aid lines like this one, which stood nearby Lange's studio in Northern California.

VIEW LARGER Dorothea Lange, <em>White Angel Bread Line, San Francisco</em> (1933). Sarah Meister, MoMA's photography curator, sees new resonance in Lange's photographs of aid lines like this one, which stood nearby Lange's studio in Northern California. But in a weird way, Meister adds, looking at Lange's work also offers a sense of solidarity across time: "You know, even a community of desperation is still a community."

Tess Taylor certainly feels that connection. The poet — and occasional NPR contributor — composed a book of poetry inspired by Lange's work, Last West, some of which was included in the MoMA exhibition. Taylor traveled throughout California, following some of Lange's own travels, and says something unmistakable still shines through the photographs.

"There's a restless desire to find a way to document the scope of this crisis — but also to make it feel human, and to capture it at a human scale," Taylor says.

That poses some difficult questions to Lange's viewers.

"What do we owe one another as a form of common dignity? How do we support one another? How is our well-being intimately welded to one another's well-being?" Taylor asks. "Those are her questions, and they're also questions that we are feeling very, very sharply right now."

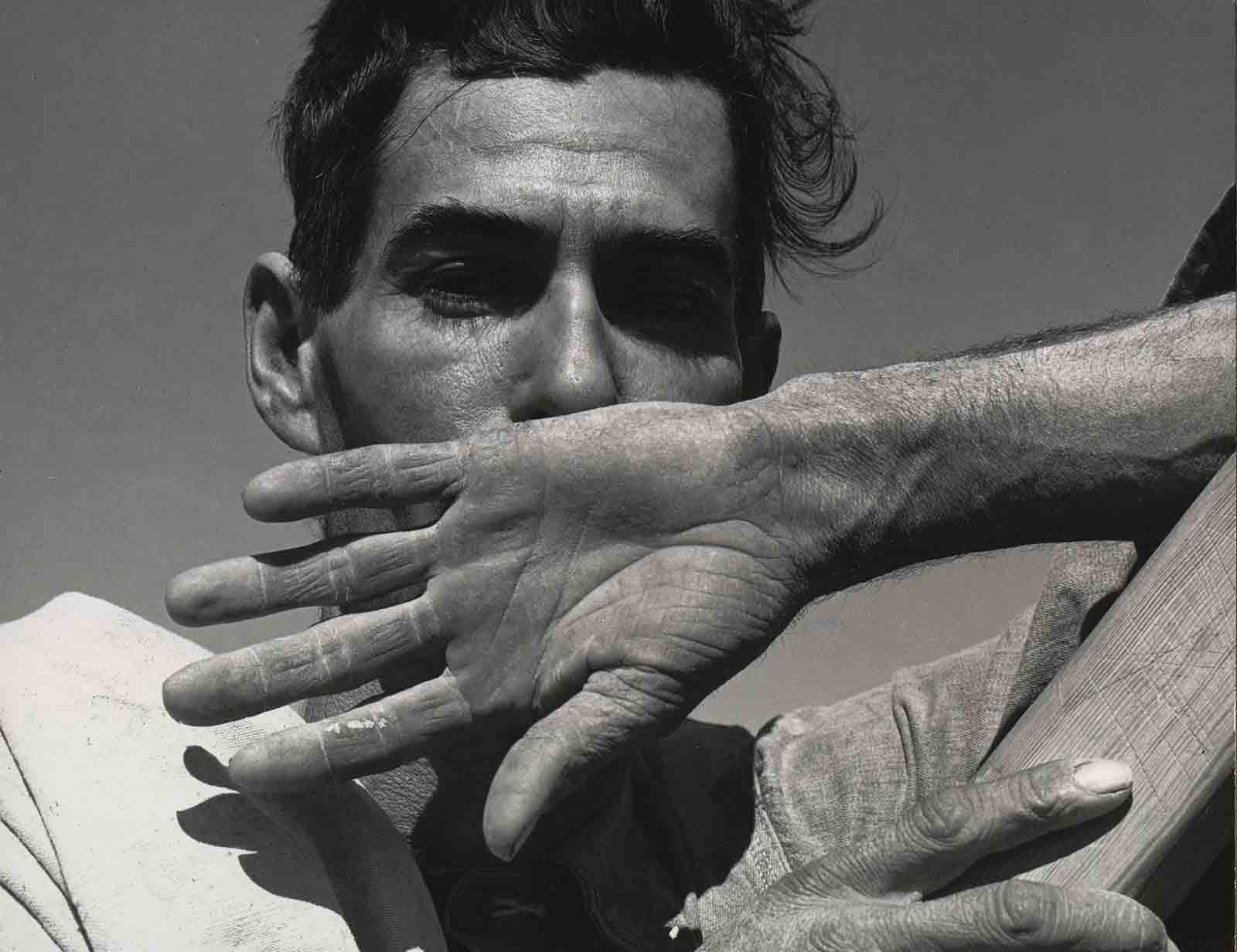

VIEW LARGER Dorothea Lange, <em>Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona</em> (1940). During many of Lange's portraits she would talk for a while with her subjects, recording their speech patterns and getting to know their perspectives on life.

VIEW LARGER Dorothea Lange, <em>Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona</em> (1940). During many of Lange's portraits she would talk for a while with her subjects, recording their speech patterns and getting to know their perspectives on life.

She says the photographer keeps coming to mind as she looks around her neighborhood, not too far from where Lange lived in the San Francisco Bay area. And as Taylor sees the melancholy menagerie of signs hanging outside her local stores — "Closed, reopening shortly, we're gone now ... [and] one store that says, 'We'll be back tomorrow,' but it's had that sign up for six weeks" — Taylor often gets out her own notebook. Since the photographer's not here to do it, the poet is taking notes for her.

Taylor doesn't know what she will do with that list yet. Then again, rarely did Lange, when she was just starting a project. It was advice she offered to young photographers.

"Don't let that question stop you," Lange explained in those early 1960s interviews. "Ways often open that are unpredictable if you pursue it far enough."

In other words, just keep your eyes and your heart open. Your notebook, too.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.