Evidence of the Bighorn Fire that burned in the Catalinas in June and July 2020.

Evidence of the Bighorn Fire that burned in the Catalinas in June and July 2020.

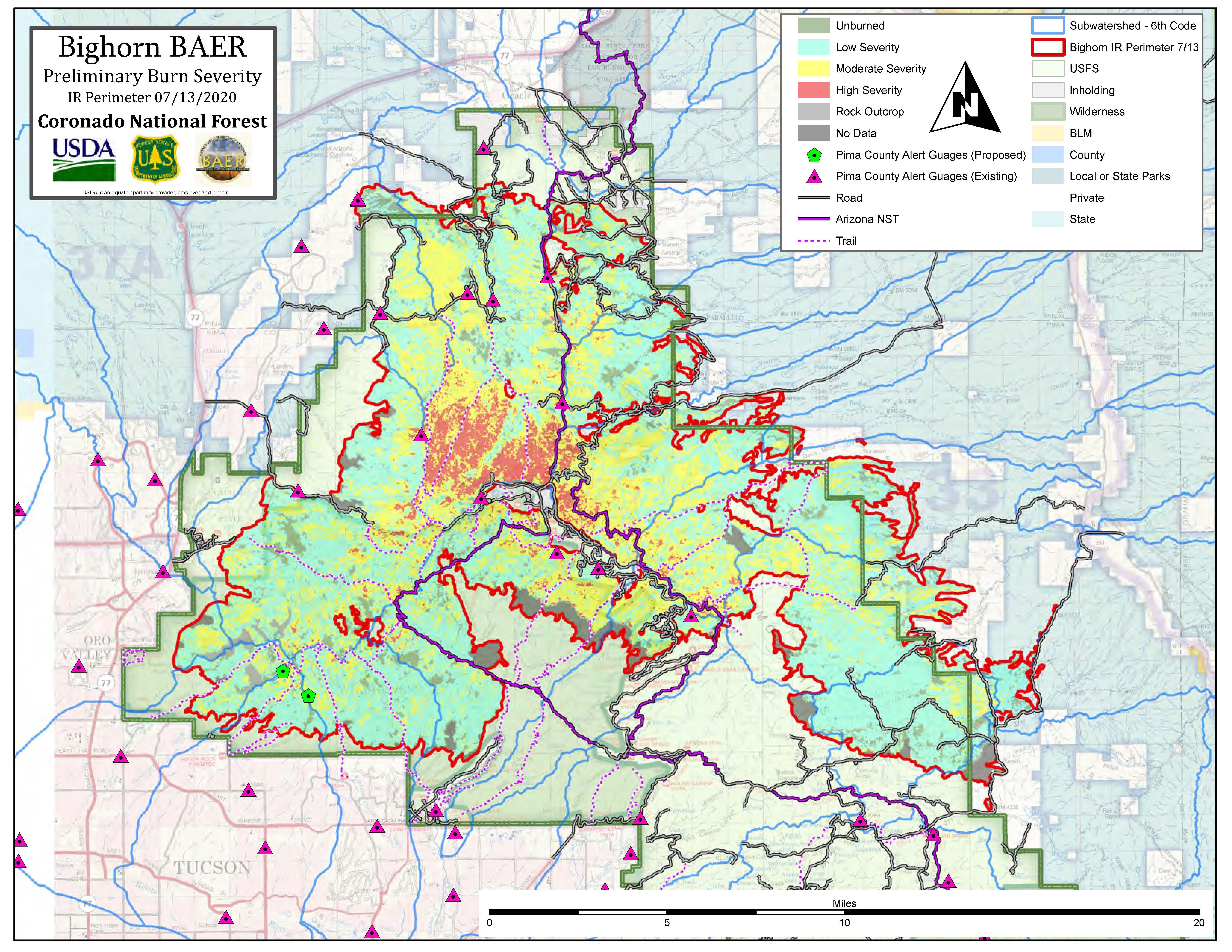

At the start of June, a lighting strike in the Pusch Ridge Wilderness set off what became known as the Bighorn Fire. Crews battled the fire for seven weeks, as it burned nearly 120,000 acres, including much-loved areas like Mt. Lemmon and the upper Sabino Canyon watershed.

From the vantage point of Tucson, the Bighorn's evacuation orders, smoke and visible flames compounded the feelings of this apocalyptic year. But from a fire standpoint, it burned like most others — in an uneven pattern of low-to-severe intensity.

The Bighorn Fire burns on Sunday, June 7, 2020 near Oro Valley, Arizona.

The Bighorn Fire burns on Sunday, June 7, 2020 near Oro Valley, Arizona.

Joshua Taiz, district wildlife biologist with the Santa Catalina Ranger District of the Coronado National Forest, said the good news is only a small percentage of the total footprint was severely burned. That was helped by the fact that the wildland firefighting crews were working to manage the fire and minimize impacts where possible, including aerial drops of water and retardant to lower the intensity of the blaze.

"Largely, it had moderate-to-mild fire effects. Which translates to moderate ecological effects," he said.

Most sky-island wildlife is well-adapted to fire and can recover quickly, and wildlife crews evacuated a couple especially vulnerable species, like fish.

On a drive up Catalina Highway in early October, much of the lower elevations looked about the same. Near the top of the mountain, singed and charred trees came into view. Just outside of Summerhaven, whole hillsides stood empty but for black tree skeletons and some early regrowth of plants like ferns. Taiz said some of the hardest-hit burn areas were those mixed-conifer forests and pine oak woodlands.

VIEW LARGER The ridge outside Summerhaven in early October 2020, months after the Bighorn Fire.

VIEW LARGER The ridge outside Summerhaven in early October 2020, months after the Bighorn Fire. "The habitat up there that we were used to seeing takes quite a while to get into that condition. So what this did was reset it down to soil in many cases," he said.

How quickly those areas will recover depends on many factors, including soil loss from future rains, seed banks and rainfall. But it will take years.

The Catalina Mountains are one of Tucson's treasures, and even for a scientist, large fires can create mixed emotions. Don Falk is a professor at the University of Arizona School of Natural Resources and the Environment and an expert in fire ecology.

"My intellect says: 'Yeah, big fire, but the majority of it low-to-moderate severity. It's a renewal process, create lots of openings, great for wildlife, everything will come back, forests are very resilient.' And my data shows all that. It's true," Falk said. "And then there's the somewhat more emotional side, which is, you know, that was my favorite place, the mixed-conifer forest."

Falk said the mountain will recover, but it will take time. This year's lack of monsoon limited some immediate runoff and erosion in burn areas, but little rain also means few seedlings have sprouted yet. Falk said after this and future fires, parts of the mountains may shift to a different mix of plants than we've been used to. Ecosystems aren't static, and the understanding we have of a place is only a short chapter in a long narrative.

"The first thing about change is that we have to think like a forest. We have to think in decades to hundreds of years, not what's going to happen in one year," he said. He said evidence suggests forest ecosystems are going to be very resilient. "But resilience, in some cases, means turning into something different, right? It's not that you're going to have a moonscape. But you may have a different ecosystem," Falk said.

VIEW LARGER

VIEW LARGER Fire is a natural part of the landscape in Arizona. But Laura Marshall, a postdoctoral fire researcher recently at the UA, said big fires in the Santa Catalina Mountains are a more recent phenomenon.

"What's really particular about the Catalinas is they've had very little fire from the year 1900 to the year 2000," she said. Marshall said that's because human activities like grazing and fire suppression kept big fires from happening.

But that leads to a build up of vegetation, "so fire, when it returns, is able to much more easily spread and become severe, especially in a severe weather event," she said.

Like the Aspen and Bullock fires in the early 2000s, which together, Marshall said, burned most of the mountain range. The Bighorn Fire burned across those same areas. Marshall pointed to the role of climate change, which has accelerated fires across the West this year.

"Climate change in particular is kind of putting a finger on the scale to push those weather events to be hotter and drier and also drying out the fuels."

VIEW LARGER Singed trees on the road up Mount Lemmon in early October, months after the Bighorn Fire.

VIEW LARGER Singed trees on the road up Mount Lemmon in early October, months after the Bighorn Fire. Falk said we need to take ownership of the fact that we've created those climate conditions. And that means our future likely holds more big fires like the Bighorn.

Coronado National Forest officials have begun reopening areas closed to public access for months. Santa Catalina District Ranger Charles Woodard said after managing the fire while it burned and letting things stabilize post-burn, they'll evaluate what work lies ahead.

"Now we are transitioning to a stage where we're looking at natural resources on ground: hydrology, ecology, biology and also our trail systems," he said. Some possible restoration tools include erosion control structures, mulching, and planting, but forest staff is still in the planning stage.

VIEW LARGER An area burned by the Bighorn Fire near Meadow Trail, June 29, according to the Inciweb tracking site.

VIEW LARGER An area burned by the Bighorn Fire near Meadow Trail, June 29, according to the Inciweb tracking site. Coronado National Forest officials closed public access during and after the fire for months. Now, they've reopened some areas and trails, but Woodard cautioned that many places, especially near the burn scar, are still unsafe.

"The mountain will continue to shift for the next three to five years and some of the areas the public absolutely should not be on these trails because they are dangerous," he said.

He said they have a lot of work to do to clear downed trees and rebuild trails, and asked the public to respect off-limits areas while crews do the work. He said due to the lack of rain during this year's monsoon season, the risk for runoff will remain for the next few years.

The process of natural regeneration and human restoration from the Bighorn Fire will continue for years, even as the cycle continues and new fires remain an ongoing threat.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.