Mountains rise above ranch land along the U.S.-Mexico border near Naco, Arizona.

Mountains rise above ranch land along the U.S.-Mexico border near Naco, Arizona.

John Ladd’s family has run cattle on the same land for more than a century. Purple mountains rise in the distance above his ocotillo and agave-studded ranch. We’re in his red truck, driving south toward the U.S.-Mexico border. I point to a white tower in the distance.

“Is that Border Patrol?” I ask.

VIEW LARGER A surveillance tower can be seen in the distance on rancher John Ladd's property.

VIEW LARGER A surveillance tower can be seen in the distance on rancher John Ladd's property. “Yeah, that’s a permanent camera,” says Ladd, one of four on his ranch. There’s also a radar station. He’s given Border Patrol access to his land for nearly 30 years, after feeling overwhelmed by the drug and human traffic across his ranch.

“They caught a half a million illegals on us, just on our ranch. Nobody believes that but a lot of people came through here,” Ladd says.

After about 15 minutes we reach the border fence, which runs the full 10.5 miles of Ladd’s ranch and beyond, built in stages about a decade ago. Here, it’s 10-foot tall mesh, with an added layer of razor wire. Ladd supports President Donald Trump and the border wall in general. He supports the recent ICE raids but also wants a new work program to encourage legal immigration. But that Washington rhetoric looks different when you live with border day in and day out.

He gestures to the mesh fence. “This is a waste of money. It’s so easy to breach that. You can climb over it, you can cut it, you can do whatever you want with it,” he says.

VIEW LARGER Rancher John Ladd opens a gate on his property where it meets the U.S.-Mexico border fence.

VIEW LARGER Rancher John Ladd opens a gate on his property where it meets the U.S.-Mexico border fence. We drive further down the border wall to a spot with 14-foot bollards — square steel posts spaced 4 inches apart. This is the kind of fencing Customs and Border Protection is planning to build across 60-some miles of desert along the Arizona border, mostly across national monuments and wildlife refuges set aside for federal protection. Those include Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and Cabeza Prieta National Widlife Refuge.

“A 30-foot high solid steel bollard wall would stop almost every wildlife species in their tracks,” says Laiken Jordahl with the Center for Biological Diversity, a conservation group currently suing the Trump administration over its waiver of dozens of environmental laws for border wall expansion.

“These are the most important environmental laws on the books,” Jordahl says. “Laws like the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act — also laws that protect cultural resources.”

VIEW LARGER Bollard-style fence along the U.S.-Mexico border on John Ladd's property.

VIEW LARGER Bollard-style fence along the U.S.-Mexico border on John Ladd's property. Conservation groups say the fencing would cause irreparable harm to the many species that depend upon critical cross-border migration corridors — even birds and butterflies. Those concerns are backed by the Fish and Wildlife Service in comments submitted to CBP about the project. And there’s one place in particular where almost no one thinks the fence is a good idea: the San Pedro River, which runs from Mexico to the U.S., near John Ladd’s property.

VIEW LARGER Vehicle barriers like this one are removed during the summer flood season on the San Pedro River.

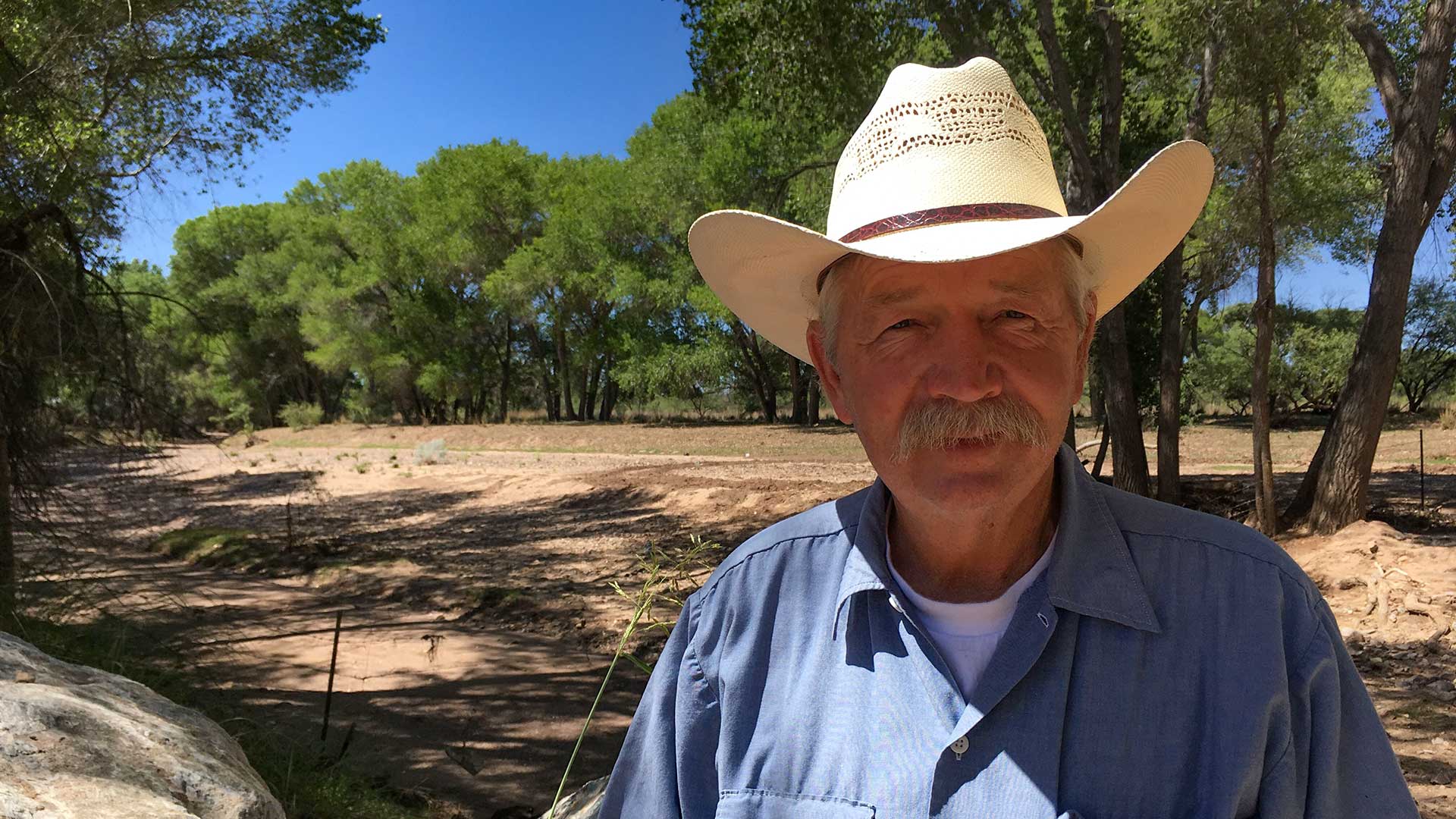

VIEW LARGER Vehicle barriers like this one are removed during the summer flood season on the San Pedro River. Nearing the river, we hop out of the truck and walk down a steep bank toward the streambed. It’s currently dry —Ladd says it’s been a dry summer — and after all, this is a desert ecosystem. But this riverbed frequently fills with massive floods during the summer monsoons. Those flows can be so intense that Border Patrol removes the vehicle barriers that are in place the rest of the year. For three months, there's no fence, just a Border Patrol agent watching the open riverbed from a truck.

Standing under a lush, verdant canopy of cottonwood and willow trees, Ladd says he’s been told CPB will build a bridge across the river with bollard fencing on top. He’s sure it will suffer at the hands of the summer floods, and thinks it’s a waste of time and money.

VIEW LARGER John Ladd's ranch has more than 10 miles of border fence on it.

VIEW LARGER John Ladd's ranch has more than 10 miles of border fence on it. “Why put yourself in that position of the liability of a structure washing out and then having to do environmental cleanup afterwards?”

Ladd’s not the only one. It its comments to CBP on the wall, the Bureau of Land Management, which manages the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, said building a border wall across the river would be an “engineering challenge.”

“Anything that would stop the passage of people through this area would also stop the flow of water,” Jordahl says. “So we’re really concerned that what they’re proposing for the San Pedro might actually create a dam and that would result in severe flooding concerns. And I think that something really special would be lost if we end up damming the last free-flowing river in Arizona with a border wall.”

VIEW LARGER The dry bed of the San Pedro River near John Ladd's property.

VIEW LARGER The dry bed of the San Pedro River near John Ladd's property. Ladd and I visit another section of bollard fencing in a low-water crossing, outfitted with 4-foot-high gates that can be opened to allow the flow of water. Piles of debris, mostly plant matter, have accumulated behind the steel posts.

“This debris comes in on the floods, and that’s why they think, ‘Oh, we can open the gate up and it’ll clean itself out.’ But it doesn’t,” Ladd says.

"I think that something really special would be lost if we end up damming the last free-flowing river in Arizona with a border wall."

Like the river barriers, these are left open all summer long to accommodate high water, providing an easy entry point. The Cochise County Sheriff’s Office says they’ve seen more success in deterring illegal immigration and drug smuggling by the recent deployment of hundreds of game cameras and convicting those they catch. Ladd agrees that a border wall isn’t the only solution.

VIEW LARGER A gate in bollard-style fencing on John Ladd's property has debris collecting in barbed wire strung along gaps under the barrier.

VIEW LARGER A gate in bollard-style fencing on John Ladd's property has debris collecting in barbed wire strung along gaps under the barrier. “Technology has a role in border security, but the bottom line is you have to have agents on the ground, and that’s never happened,” he says.

We saw three or four border patrol vehicles in a couple of hours traveling along this section of border wall, but Ladd says that’s not nearly enough.

CBP didn’t respond to an interview request by deadline, but in recent documents filed in the legal challenge the agency indicated it still hasn’t finalized plans for the San Pedro wall segment and is planning to do geotechnical surveys of the riverbed in September. Construction is currently slated to begin as early as October.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.