Deer dancer statue outside of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe's administration building.

Deer dancer statue outside of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe's administration building.

Arizona's binational tribes

Tribes that are federally recognized have a formal relationship with the United States, and can receive funding and services, like health care and education, from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. But gaining that federal recognition can be complicated, especially for tribes that inhabit lands on both sides of an international boundary.

This week The Buzz talked with two Southern Arizona tribes about how their sovereignty and way of life is complicated by their location on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border.

AZPM’s Indigenous communities reporter Emma Gibson talked with Pascua Yaqui Chairman Robert Valencia about how his tribe gained federal recognition in the 1970s.

“So, we got the land in '64. It was formerly Bureau of Land Management land. Although it was out here in the desert, it was something that we hadn’t had before, any type of land tract.”

Although the Pascua Yaqui didn’t get federally recognized until the late 20th century, they have inhabited the land that is now Arizona for hundreds of years.

"We believe we have been here forever and a day,” said Valencia. “You know, one of the things that’s missing is our own version of what our history is and our presence is. Everyone writes about us as if we didn’t exist before then."

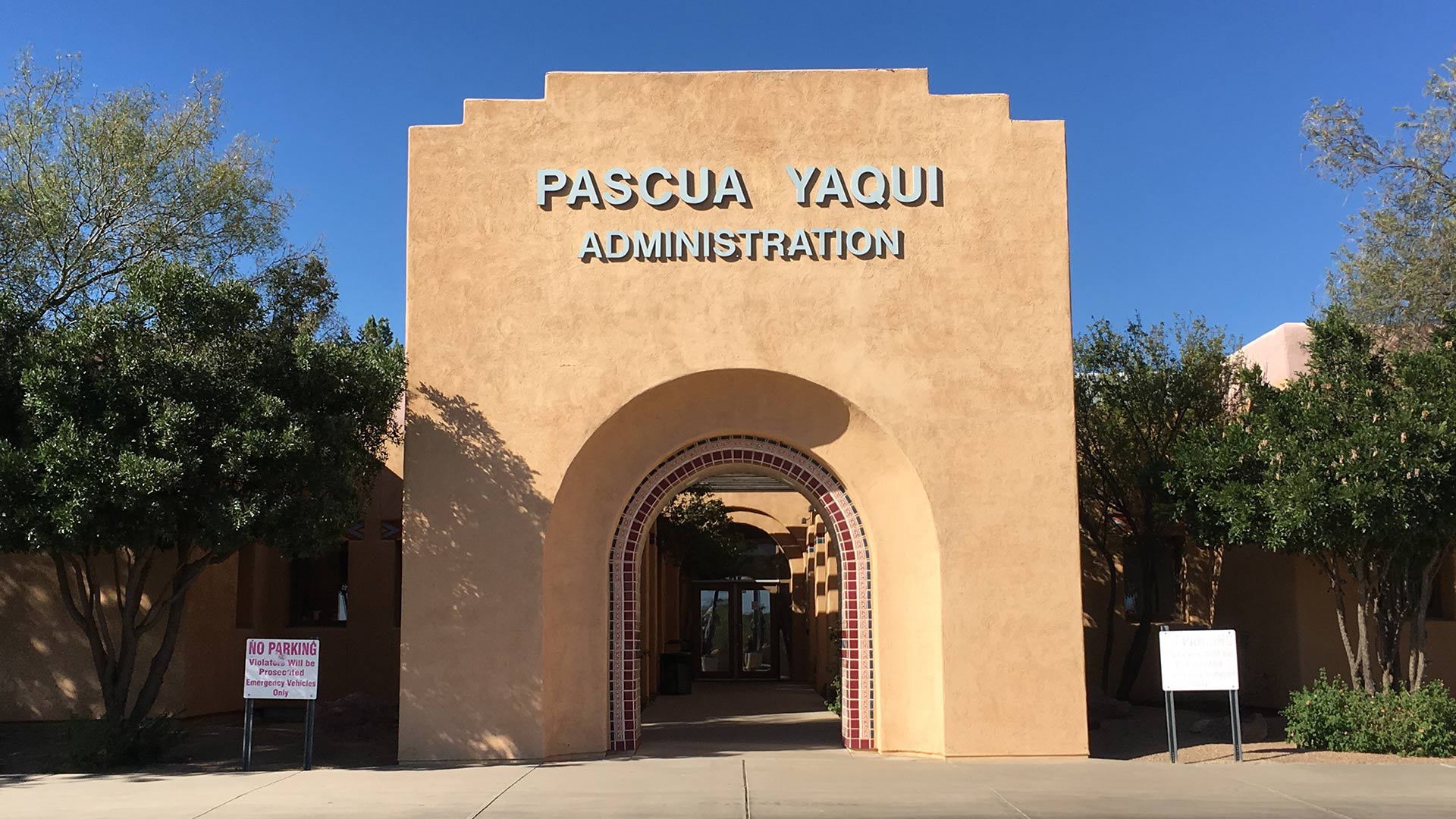

VIEW LARGER The administration building of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe.

VIEW LARGER The administration building of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe. Historian Brenden Rensink wrote the book Native but Foreign which focuses on the history of the Yaqui and other cross-border tribes. His book explores the ways national borders affect the Indigenous peoples who inhabited those lands before borders existed, and what it means to be "Indigenous," or an "immigrant." Rensink told The Buzz during the last few centuries the Yaqui traveled to what is now Arizona in part for economic reasons.

"They came up very early on with Spanish missionaries, later in the 1800s they were expanding greatly and participating in mining all across the American Southwest. ... [They] were joined later in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by waves of Yaquis who came as political refugees — who were fleeing violence in Sonora, fleeing extermination, enslavement and deportation by the Mexican government. Those groups came up and settled in Arizona as well.”

Rensink said despite that history, it took a long time for the tribe to be federally recognized.

"For some families it was over 100 years of living in Arizona as a distinct and unique Indigenous community, but not being recognized by the U.S. federal government as American Indians," he said.

The Tohono O’odham Nation reservation, established in 1917, stretches approximately 60 miles along the southern border with Mexico. After the Navajo Nation, it’s the second-largest reservation in the country. AZPM’s Emma Gibson talked to Dwayne Pierce, a history instructor at the Tohono O’odham Community College, about the tribe’s experience being split by the U.S.-Mexico border.

"The border is kind of like an imaginary line for the O’odham people. Because the whole thing was O’odham land stretching from the Gila River down to the Sonora River. That’s how a lot of the O’odham people saw it probably until the '50s or '60s. Most O’odham people do not think of themselves as a transnational entity of any kind," Pierce told The Buzz.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.