UA astronomer David Sand discovered supernova SN 2017cbv in March 2017 when he was with the Las Cumbres Observatory in California.

UA astronomer David Sand discovered supernova SN 2017cbv in March 2017 when he was with the Las Cumbres Observatory in California.

An astronomer at Steward Observatory in Tucson was among the first ever to observe the collision of two dense stars in deep space.

The discovery was announced Monday morning at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., and David Sand was among those presenting their findings.

On Aug. 17, scientists around the globe observed two neutron stars merging, something that astronomers had theorized but never documented.

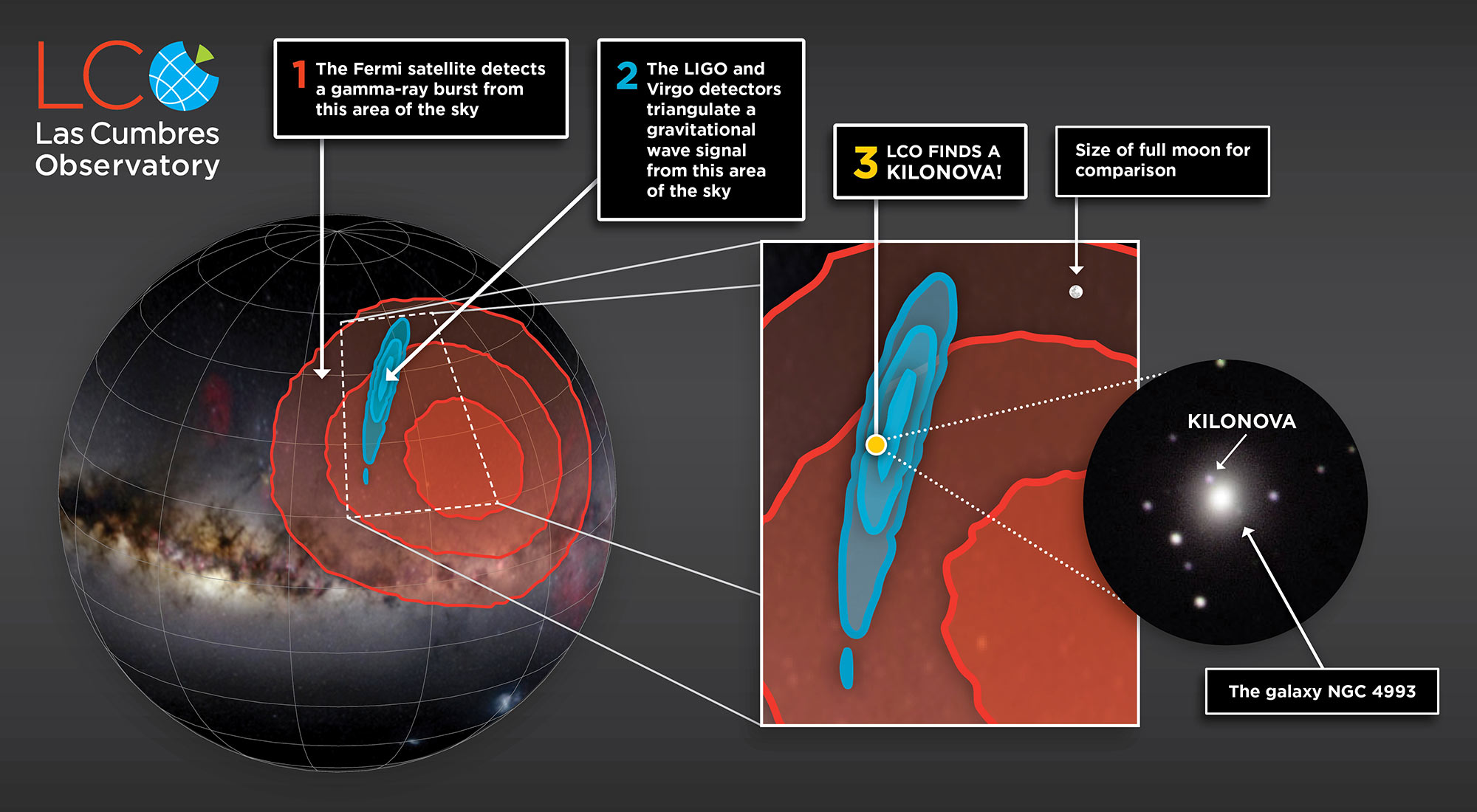

The event, called a kilonova, was initially sensed through gravitational waves by detectors at three locations on Earth. Astronomers were able to point telescopes in the direction the waves were coming from to see the collision, 130 million light years away.

VIEW LARGER An illustration depicting how the kilonova was observed.

VIEW LARGER An illustration depicting how the kilonova was observed. Sand, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Arizona, remotely operates a 16-inch telescope in Chile as part of his quest to discover supernovas. His group looks at 500 galaxies a night.

After the gravitational wave alert came in August, Sand and his team trained the telescope on the area of the sky from where the waves came. His observation group and several others also with telescopes in Chile announced they "saw" the astronomical phenomenon within minutes of each other, he said.

Sand said once his team examined two images of the kilonova, "we knew for a fact it was something new. We followed it with our little telescope for several days, and it didn't look like any supernova we'd ever seen before. This thing started relatively bright and faded away within five days."

Sand's team made its observation about 11 hours after the wave alert went out because the telescope was in daylight at the time of the first notification. That gave them time to refine where to aim the instrument as more data came from the wave detectors.

“One thing that is exciting about this event is, my background is in physics and so I am very interested in the physics of these things coalescing, but the other thing we can learn about, ultimately, when we gather more of these events, is how fast the universe is expanding,” Sand said.

The first detection of gravitational waves was made in September 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational wave Observatory, or LIGO, whose detectors are in Louisiana and Washington state. The waves’ discoverers were honored with this year’s Nobel Prize for physics.

LIGO, along with a similar detector in Italy, sensed the kilonova's gravitational waves, and NASA's Fermi satellite detected a burst of gamma rays from the August event, setting the astronomers in action to try to see what the other instruments had sensed, Sand said.

Gravitational waves provide "a new way of looking at the universe," he said,

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.